The Sentry

Wilfred Owen

1893 to 1918

We’d found an old Boche dug-out, and he knew,

And gave us hell, for shell on frantic shell

Hammered on top, but never quite burst through.

Rain, guttering down in waterfalls of slime

Kept slush waist high, that rising hour by hour,

Choked up the steps too thick with clay to climb.

What murk of air remained stank old, and sour

With fumes of whizz-bangs, and the smell of men

Who’d lived there years, and left their curse in the den,

If not their corpses...

There we herded from the blast

Of whizz-bangs, but one found our door at last.

Buffeting eyes and breath, snuffing the candles.

And thud! flump! thud! down the steep steps came thumping

And splashing in the flood, deluging muck —

The sentry’s body; then his rifle, handles

Of old Boche bombs, and mud in ruck on ruck.

We dredged him up, for killed, until he whined

“O sir, my eyes — I’m blind — I’m blind, I’m blind!”

Coaxing, I held a flame against his lids

And said if he could see the least blurred light

He was not blind; in time he’d get all right.

“I can’t,” he sobbed. Eyeballs, huge-bulged like squids

Watch my dreams still; but I forgot him there

In posting next for duty, and sending a scout

To beg a stretcher somewhere, and floundering about

To other posts under the shrieking air.

Those other wretches, how they bled and spewed,

And one who would have drowned himself for good, —

I try not to remember these things now.

Let dread hark back for one word only: how

Half-listening to that sentry’s moans and jumps,

And the wild chattering of his broken teeth,

Renewed most horribly whenever crumps

Pummelled the roof and slogged the air beneath —

Through the dense din, I say, we heard him shout

“I see your lights!” But ours had long died out.

Wilfred Owen's The Sentry

Introduction

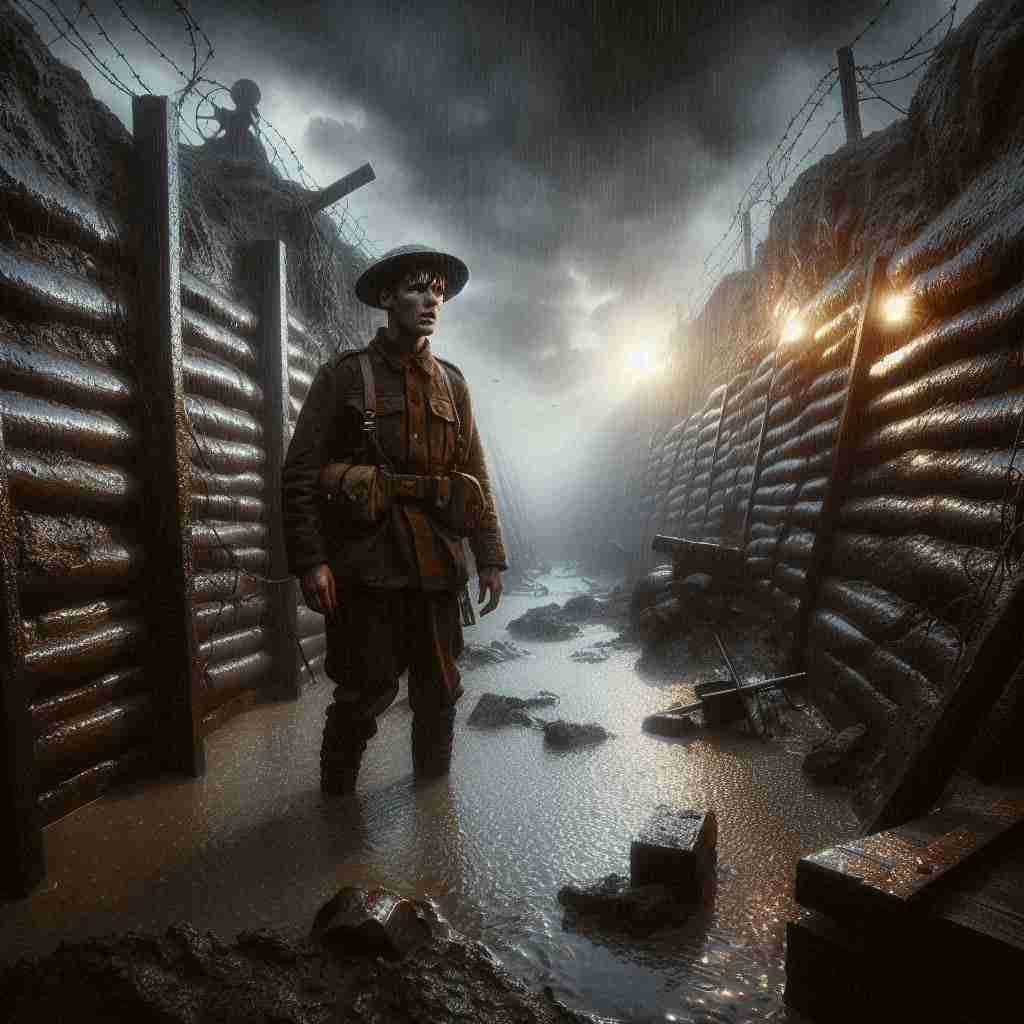

Wilfred Owen's "The Sentry" stands as a haunting testament to the brutal realities of trench warfare during World War I. This poem, written in 1918 shortly before Owen's tragic death in combat, offers a visceral and deeply personal account of the psychological and physical trauma endured by soldiers on the front lines. Through its vivid imagery, stark sensory details, and unflinching portrayal of human suffering, "The Sentry" emerges as one of the most powerful and disturbing works in the canon of war poetry.

Historical Context and Biographical Significance

To fully appreciate the depth and significance of "The Sentry," one must first consider its historical context and Owen's personal experiences as a soldier. Composed during Owen's convalescence at Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh, the poem draws directly from his experiences in the trenches of the Western Front. The specific incident described in the poem occurred in January 1917 near the French village of Savy-Berlette, where Owen served as a second lieutenant in the Manchester Regiment.

Owen's firsthand experience of the horrors of war profoundly shaped his poetic voice and artistic mission. Unlike the patriotic verses that dominated much of the early war poetry, Owen sought to convey the stark truth of combat, famously declaring his intent to speak "the truth untold, / The pity of war, the pity war distilled." "The Sentry" exemplifies this commitment, offering an unflinching look at the physical and psychological toll of warfare on individual soldiers.

Structure and Form

The poem consists of 30 lines of varying length, eschewing a rigid formal structure in favor of a more organic flow that mirrors the chaotic and unpredictable nature of trench warfare. While not adhering to a strict rhyme scheme, Owen employs occasional rhymes and near-rhymes throughout the piece, creating a sense of cohesion amidst the disorder.

The poem's structure can be roughly divided into three sections: the description of the dugout and initial bombardment (lines 1-9), the arrival of the wounded sentry (lines 10-23), and the haunting aftermath (lines 24-30). This tripartite structure mirrors the progression of a traumatic experience: the tense buildup, the shocking central event, and the lingering psychological impact.

Imagery and Sensory Detail

One of the most striking aspects of "The Sentry" is its reliance on vivid, often grotesque imagery to convey the sensory assault of trench warfare. Owen bombards the reader with a cacophony of sights, sounds, smells, and tactile sensations, creating an immersive and deeply unsettling reading experience.

The poem opens with a description of the dugout that assaults multiple senses simultaneously. The "shell on frantic shell" creates a deafening auditory backdrop, while the "rain, guttering down in waterfalls of slime" evokes both visual and tactile discomfort. The air itself becomes a palpable presence, thick with "fumes of whizz-bangs, and the smell of men / Who'd lived there years."

This sensory onslaught reaches its peak with the arrival of the wounded sentry. The "thud! flump! thud!" of his body tumbling down the steps is followed by the grotesque image of his "eyeballs, huge-bulged like squids." The sentry's suffering is conveyed through a combination of visual detail ("I held a flame against his lids"), auditory cues ("wild chattering of his broken teeth"), and his own anguished cries ("O sir, my eyes — I'm blind — I'm blind, I'm blind!").

By immersing the reader in this sensory maelstrom, Owen forces us to confront the visceral reality of warfare in a way that mere description could never achieve. The cumulative effect is one of overwhelming disorientation and horror, mirroring the psychological state of the soldiers themselves.

Themes and Symbolism

While "The Sentry" is grounded in concrete, physical details, it also explores deeper themes and employs powerful symbolism. The central image of blindness serves as both a literal injury and a potent metaphor for the broader impact of war on the human psyche. The sentry's loss of sight represents not only his physical wound but also the loss of innocence and hope experienced by countless soldiers.

The recurring motif of light and darkness throughout the poem reinforces this theme. The soldiers struggle to maintain their candles in the face of bombardment, symbolic of their tenuous grip on hope and sanity. The sentry's final cry of "I see your lights!" when all lights have been extinguished is particularly haunting, suggesting either a desperate clinging to false hope or a descent into madness.

The poem also grapples with the theme of duty versus humanity. The speaker's internal conflict is evident as he struggles to balance his responsibilities as an officer ("posting next for duty") with his compassion for the wounded sentry and other suffering soldiers. This tension reflects the broader ethical dilemmas faced by soldiers in wartime, forced to reconcile their military obligations with their innate human empathy.

Language and Tone

Owen's mastery of language is on full display in "The Sentry," as he employs a range of poetic techniques to heighten the emotional impact of the piece. The use of onomatopoeia ("thud! flump! thud!") and alliteration ("shell on frantic shell / Hammered on top") creates a sonic landscape that mirrors the chaos of battle.

The poem's diction is a carefully calibrated mix of colloquial soldier's slang ("Boche," "whizz-bangs") and more elevated language, reflecting the surreal juxtaposition of the mundane and the horrific in wartime. This linguistic tension contributes to the overall sense of disorientation and unease that permeates the poem.

The tone of "The Sentry" is one of barely contained anguish and horror. While the speaker attempts to maintain a degree of detachment, particularly in the early stanzas, the accumulation of horrific details and the sentry's suffering ultimately overwhelm any semblance of emotional distance. The final lines, with their haunting admission "I try not to remember these things now," reveal the lasting psychological scars inflicted by such experiences.

Comparative Analysis

"The Sentry" can be productively compared to other works in Owen's oeuvre, particularly his more famous poems such as "Dulce et Decorum Est" and "Anthem for Doomed Youth." While these better-known pieces often employ more traditional forms and rhetorical structures, "The Sentry" stands out for its raw, almost stream-of-consciousness approach to conveying the chaos of combat.

In the broader context of World War I poetry, "The Sentry" aligns closely with the work of other soldier-poets like Siegfried Sassoon and Isaac Rosenberg, who similarly sought to convey the brutal realities of trench warfare. However, Owen's unique combination of visceral imagery, sophisticated language, and deep empathy for his fellow soldiers sets his work apart, cementing his status as one of the preeminent voices of his generation.

Conclusion

"The Sentry" stands as a powerful testament to Wilfred Owen's poetic genius and his unwavering commitment to bearing witness to the horrors of war. Through its vivid imagery, complex themes, and masterful use of language, the poem offers a searing indictment of the human cost of conflict. More than a century after its composition, "The Sentry" remains a deeply affecting and relevant work, forcing readers to confront uncomfortable truths about war, duty, and the fragility of the human spirit in the face of overwhelming violence.

As we continue to grapple with the legacy of World War I and the ongoing realities of armed conflict in our own time, Owen's unflinching portrayal of the physical and psychological toll of warfare serves as a crucial reminder of the true nature of combat. "The Sentry" challenges us to look beyond patriotic rhetoric and sanitized accounts of battle, compelling us to confront the stark, often brutal truth of war and its lasting impact on those who experience it firsthand.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!