Rima LIII (Spanish)

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer

1836 to 1870

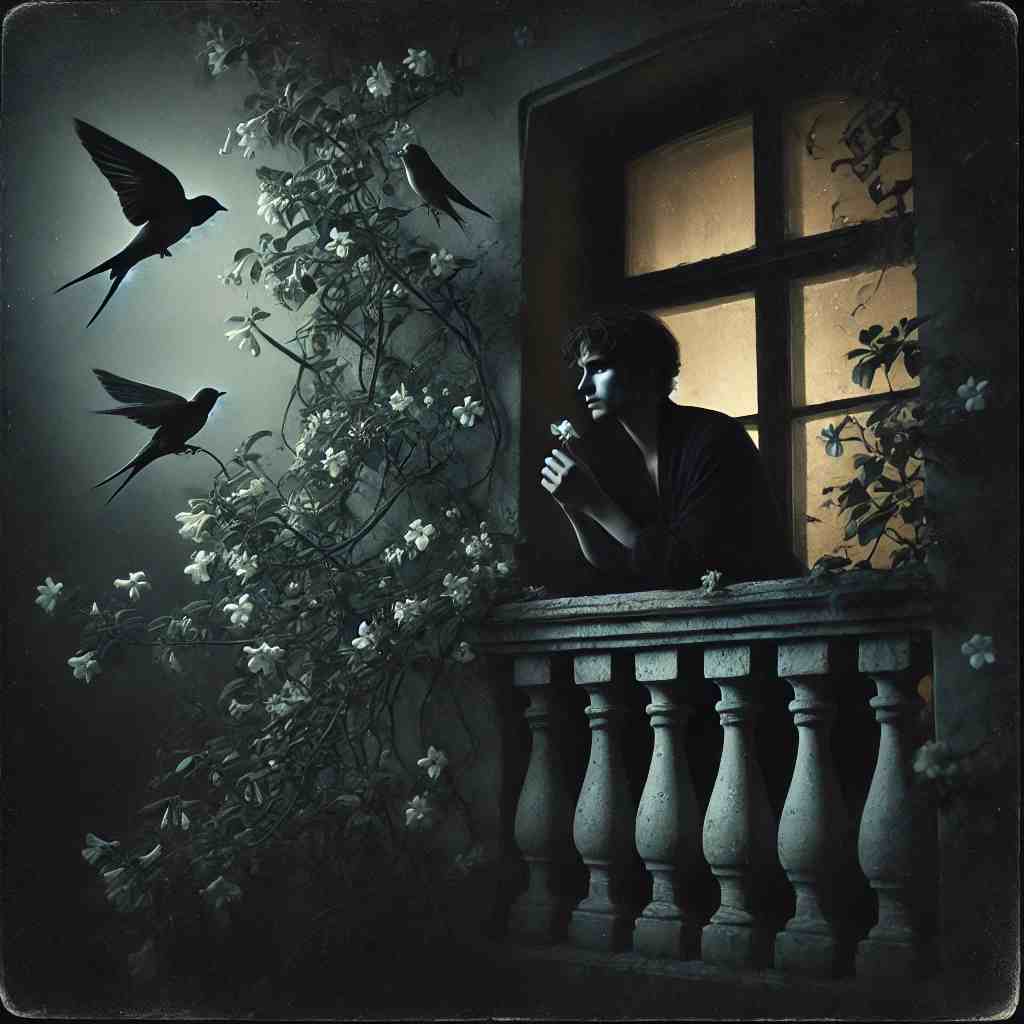

Volverán las oscuras golondrinas

en tu balcón sus nidos a colgar,

y otra vez con el ala a sus cristales

jugando llamarán.

Pero aquellas que el vuelo refrenaban

tu hermosura y mi dicha a contemplar,

aquellas que aprendieron nuestros nombres....

ésas... ¡no volverán!

Volverán las tupidas madreselvas

de tu jardín las tapias a escalar

y otra vez a la tarde aún más hermosas

sus flores se abrirán.

Pero aquellas cuajadas de rocío

cuyas gotas mirábamos temblar

y caer como lágrimas del día....

ésas... ¡no volverán!

Volverán del amor en tus oídos

las palabras ardientes a sonar,

tu corazón de su profundo sueño

tal vez despertará.

Pero mudo y absorto y de rodillas

como se adora a Dios ante su altar,

como yo te he querido..., desengáñate,

así... ¡no te querrán!

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer's Rima LIII

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer's "Rima LIII" is one of the most celebrated works of Spanish Romanticism, offering a poignant meditation on love, loss, and the uniqueness of shared experiences. Through the repetition of natural imagery and contrasts between the cyclical and the irreplaceable, Bécquer evokes a sense of melancholy and resignation, highlighting the impossibility of recreating a love that was once deeply meaningful. The poem’s structure, language, and thematic dualities contribute to its enduring power and universal appeal.

Structure and Form

"Rima LIII" is composed of three quatrains with an ABAB rhyme scheme, in which alternating rhymes emphasize the rhythmic flow of memory and return. Each quatrain opens with a pattern: an assertion of what will return, only to be followed by an emotional denial of what will not return. This oscillation between return and loss captures the paradox of nature’s repetition and human uniqueness, setting up a contrast that underscores the speaker’s grief.

Stanza-by-Stanza Analysis

First Stanza

"Volverán las oscuras golondrinas

en tu balcón sus nidos a colgar,

y otra vez con el ala a sus cristales

jugando llamarán."

In the first stanza, Bécquer introduces the theme of return through the image of golondrinas (swallows), birds often associated with seasonal migration and cyclical return. The swallows are described as “oscuras” (dark), suggesting shadows of the past. They will return to “your balcony” to nest, hinting at a shared space once filled with love. By depicting them “playing” against the glass of the beloved’s window, Bécquer invokes a lighthearted image that, upon closer reading, becomes bittersweet; this joyous return is ultimately a reminder of absence and unfulfilled longing.

"Pero aquellas que el vuelo refrenaban

tu hermosura y mi dicha a contemplar,

aquellas que aprendieron nuestros nombres....

ésas... ¡no volverán!"

In the second half of the stanza, the speaker makes a profound distinction: while swallows will return, those specific swallows—the ones that once bore witness to the couple’s love—will not. This distinction between the general and the particular is key to the poem’s emotional depth. The use of the pronoun “aquellas” (those) personifies the swallows as entities tied to the unique memory of a love that has passed. The mournful refrain, “ésas… ¡no volverán!” underscores the irreplaceable nature of that specific past, a memory suspended in time and impossible to recreate.

Second Stanza

"Volverán las tupidas madreselvas

de tu jardín las tapias a escalar

y otra vez a la tarde aún más hermosas

sus flores se abrirán."

The second stanza shifts from the image of swallows to honeysuckle (madreselvas), climbing and blooming in the beloved’s garden. The flowers evoke themes of growth, natural beauty, and renewal, and their description as “tupidas” (thick) suggests abundance and vitality. Like the swallows, the honeysuckle represents a cycle in nature that will persist even without the presence of love.

"Pero aquellas cuajadas de rocío

cuyas gotas mirábamos temblar

y caer como lágrimas del día....

ésas... ¡no volverán!"

In contrast, the speaker mourns the loss of specific flowers “cuajadas de rocío” (covered in dew), whose drops they once watched together. The metaphor comparing dew to “tears of the day” captures the fleeting, delicate nature of their past intimacy. The allusion to tears gives the natural image an emotional weight, as if nature itself mourns the loss of this shared experience. The repetition of “ésas… ¡no volverán!” intensifies the feeling of irretrievable loss and positions these moments of past beauty as both transient and sacred.

Third Stanza

"Volverán del amor en tus oídos

las palabras ardientes a sonar,

tu corazón de su profundo sueño

tal vez despertará."

The third stanza addresses the return of love itself, suggesting that “ardent words” may once again resonate in the beloved’s ears, and her heart may “awaken from its deep sleep.” This awakening implies the possibility of new love, yet it is juxtaposed with the speaker’s clear statement that such love will never be the same. The language of passion (“ardientes”) contrasts with the speaker's resignation, hinting at a love that might stir the beloved but will lack the depth and authenticity of what they once shared.

"Pero mudo y absorto y de rodillas

como se adora a Dios ante su altar,

como yo te he querido..., desengáñate,

así... ¡no te querrán!"

The final lines reach the poem’s emotional apex. The speaker emphasizes the intensity and uniqueness of his love, which he compares to worship (“como se adora a Dios ante su altar”). Here, the speaker’s devotion is elevated to a near-sacred act, underscoring the purity and depth of his past feelings. By ending on “¡no te querrán!” he asserts with painful finality that no one will love the beloved in this manner again. The imperative “desengáñate” (disillusion yourself) is a bold statement that demands acceptance of this truth, both from the beloved and the reader.

Themes and Symbols

-

Irreversible Loss: Each stanza affirms that while certain things may return, the specific manifestations of shared love will not. This creates a haunting sense of finality that permeates the poem.

-

Nature as a Mirror of Emotion: The recurring images of swallows, honeysuckle, and dew-laden flowers serve as symbols for the fleeting beauty of love. They reflect both nature’s cyclical patterns and the uniqueness of human experience, framing love as something both ephemeral and, in its singular form, unrepeatable.

-

The Sacredness of True Love: The speaker’s final comparison of his love to religious devotion suggests that true love, once experienced, becomes sacrosanct. This spiritual dimension elevates the speaker’s sorrow into a transcendent statement about the rarity of genuine, selfless love.

Conclusion

"Rima LIII" by Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer captures the bittersweet reality of love’s impermanence with haunting imagery and a restrained yet impassioned voice. Bécquer’s use of cyclical images from nature to contrast the irreplaceability of a specific love underscores a Romantic preoccupation with memory, individual experience, and emotional depth. The refrain, “ésas… ¡no volverán!” reverberates throughout the poem, echoing the universal human longing for what once was, and reminding us that some loves, however briefly they blossom, leave an indelible mark on the heart. Through his masterful use of language, Bécquer invites readers to mourn not just a personal loss but the ephemeral nature of beauty and love itself.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!