Sinking of the Mendi (Xhosa)

S.E.K. Mqhayi

1875 to 1945

Ukutshona kukamendi

Ewe, le nto kakade yinto yaloo nto-

Thina, nto zaziyo, asothukanga nto!

Sibona kamhlophe, sithi bekumelwe;

Sitheth'engqondweni, sithi kufanelwe.

Xa bekungenjalo bekungayi kulinga,

Ngoko ke, SoTase! Kwaqal'ukulunga!

Le nqanaw'uMendi namhla yendisile,

Nal'igazi lethu lisikhonzisile!

Asinithumanga ngazo izicengo;

Asinithenganga ngayo imibengo.

Bekungenganzuzo zimakhwezi-khwezi;

Bekungengandyebo zingangeenkwenkwezi-

Sikwatsho nakuni, bafel'eAfrika,

KwelaseJamani yaseMpuma-langa-bekungembek'eninayo kuKumkani,

bekungentobeko yenu kwiBritani.

Mhla nashiy'ikhaya sithethille nani,

Mhla nashiy'intsapho salathile kuni,

Mhla sabamb'izandla, mhla kwamanz'amehlo;

Mhla balil'onyoko, bangqukrelek'oyihlo;

Mhla nashiy'ikhaya sithethile nani,

Mhla nashiy'intsapho salathile kuni,

Mhla sabamb'izandla, mhla kwamanz'amehlo;

Mhla balil'onyoko, bangqukrelek'oyihlo;

Mhla nazishiy'ezi ntaba zakowenu,

Nayininikel'imiva imilamb'ezwe lenu,

Asitshongo na kuni, midak'akowethu,

Ukuthi, "Kwelo zwe nilidini lethu!?

Ngesibinge ngantoni na ka kade?

Idini lomzi liyintoni na kade?

Asingamathol'amaduna omzi na?

Asizizithandwa zesizwe kade na?

Ngoku kuthetha ke siyendelisela,

Sibhekis'ezantsi, sihlahla indlela.

AsinguHabheli n'elomhlaba idini?

AsinguMesiya n' elaseZulwini?

Thuthuzelekani ngoko, zinkedama;

Kuf'pmnye kakade, mini kwakhiw'omnye;

Kukhonza mnye kade, zekuphil'omnye.

Ngokwenjenje kwethu sithi, yakhekani;

Lithabatheni eli qhalo labadala:

Kuba bathi, "Akuhlanga lungehlanga!"

Awu! Zaf'iint'ezinkulu zeAfrika!

Isindiwe le nqanawa 'de yazika,

Kwaf'amakhalipha, amafa-nankosi.

Ukufa kwawo kunomvuzo nomvuka.

Ndinga ndingema nawo ngoMhla woKuvuka,

Ndingqambe njengomnye osebenzileyo,

Ndikhanye njengoMso oqaqambileyo.

Makube njalo.

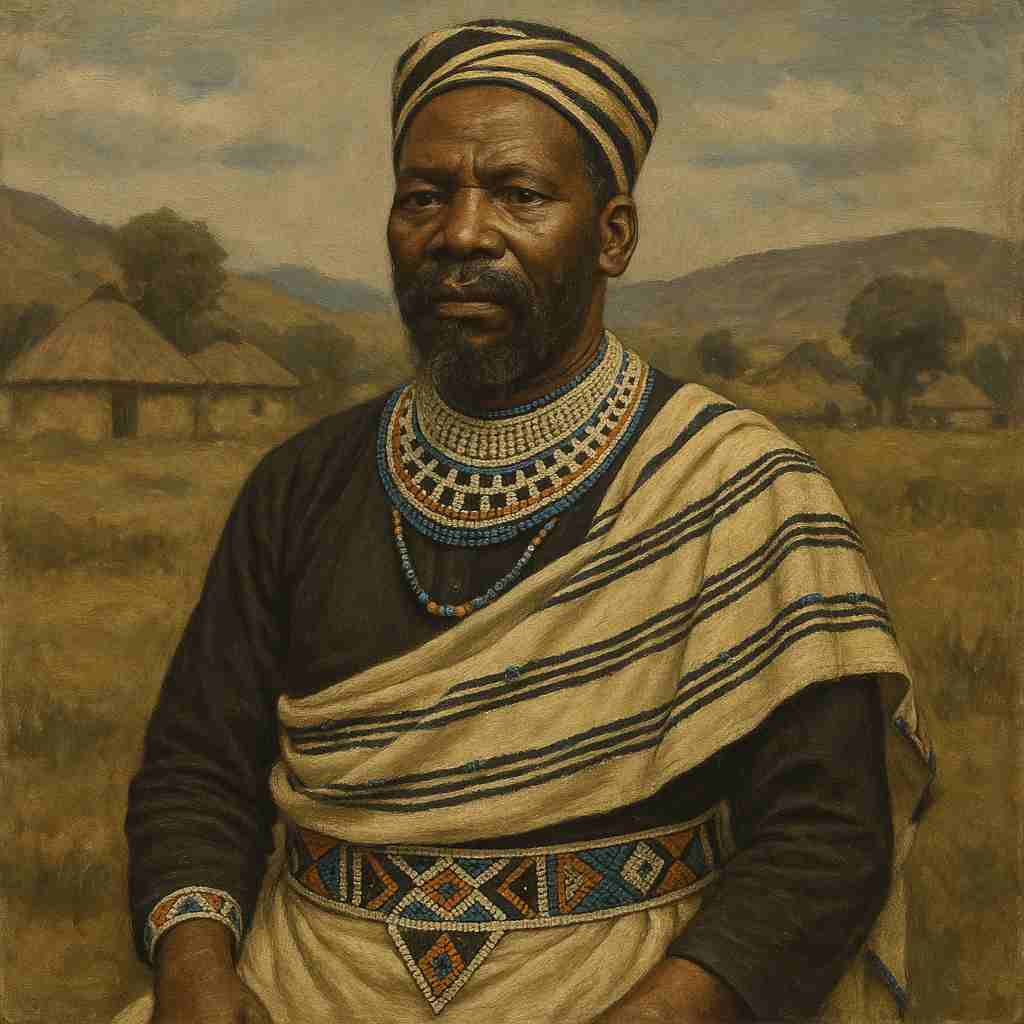

S.E.K. Mqhayi's Sinking of the Mendi

The "Sinking of the Mendi" by S.E.K. Mqhayi stands as one of the most significant poems in South African literature, commemorating the tragic sinking of the SS Mendi in 1917, where over 600 South African Native Labour Corps members perished in the English Channel during World War I. Mqhayi's elegiac masterpiece transcends mere historical documentation, weaving together traditional African oral poetry forms with profound theological and philosophical reflections on sacrifice, destiny, and the complex relationship between colonial powers and African subjects.

Historical Context and Political Significance

The poem's historical backdrop is crucial to understanding its multilayered meanings. The sinking of the SS Mendi represented one of South Africa's worst maritime disasters, yet it carried additional weight as a symbol of African participation in a European war. Mqhayi's opening lines "Yes, indeed this was meant to be— / We, who know, are not shocked to see!" establish an immediate tension between acceptance and critique of colonial power structures.

The poet's reference to "We, who know" suggests an indigenous wisdom that transcends the immediate tragedy, positioning African understanding as equal to, if not superior to, colonial knowledge systems. This subtle subversion continues throughout the work, particularly in lines like "It wasn't your loyalty to the King, / Nor to Britain's crown offering," which directly challenges the colonial narrative of willing African participation in the war effort.

Poetic Structure and Traditional Elements

Mqhayi masterfully employs traditional isiXhosa poetic techniques while creating a work that speaks to both African and Western literary traditions. The poem's structure, with its consistent rhyming couplets in the original isiXhosa, echoes the call-and-response pattern of traditional praise poetry while maintaining a formal elegance that would be recognized in Western poetic traditions.

The repetition of key phrases, particularly in the stanza "When you left home, we spoke with you, / When you left family, we showed you true," demonstrates the poem's oral heritage while serving the dramatic purpose of emphasizing the magnitude of the sacrifice being commemorated. This repetition creates a rhythmic drumbeat throughout the work, reminiscent of both traditional African ceremonies and the marching cadence of soldiers.

Religious and Sacrificial Imagery

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Mqhayi's poem is its sophisticated integration of Christian and traditional African religious imagery. The references to Abel and the Messiah ("Are we not like Abel's earth offering? / Are we not like Heaven's Messiah bringing?") create a powerful syncretic religious framework that elevates the soldiers' sacrifice to a sacred level.

The sacrificial theme is developed through multiple layers of meaning. The direct comparison to Abel's offering suggests both the purity of the sacrifice and its tragic nature, while the Messianic parallel introduces a redemptive element to the soldiers' deaths. This Christian imagery is seamlessly interwoven with traditional African concepts of sacrifice for the community, as evidenced in the lines "What's the home's sacrifice, do you know? / Are we not the male calves of home?"

Colonial Critique and Resistance

While maintaining a tone of dignity and restraint, Mqhayi embeds a sophisticated critique of colonialism within the poem's elegiac framework. The repeated emphasis on "We did not send you with mere pleas; / We did not buy you with small fees" serves to undermine any suggestion that African participation in the war was driven by material gain or colonial coercion.

The poem's treatment of the relationship between African soldiers and colonial authorities is particularly nuanced. Rather than presenting a simple narrative of exploitation, Mqhayi constructs a complex understanding of sacrifice that maintains African agency while acknowledging the tragic circumstances of colonial participation in the war.

Prophetic Vision and Resolution

The poem's concluding section moves from historical commemoration to prophetic vision. The speaker's desire to "stand with them on Rising Day" transforms the specific historical tragedy into an eschatological moment. This temporal shift is significant, suggesting that the meaning of the Mendi sacrifice extends beyond its historical moment into a future where justice and recognition will be realized.

The final lines, with their image of shining "like Tomorrow's brightest ray," create a powerful sense of hope and redemption while maintaining the poem's engagement with both Christian and African spiritual traditions. The closing "So let it be" echoes both Christian "Amen" and traditional African affirmations, creating a fitting conclusion to the poem's synthetic achievement.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Mqhayi's "Sinking of the Mendi" remains remarkably relevant to contemporary discussions of historical memory, sacrifice, and post-colonial identity. The poem's sophisticated treatment of sacrifice, resistance, and redemption offers valuable insights into how communities can commemorate tragedy while maintaining dignity and agency.

The work's ability to speak simultaneously to different cultural traditions while maintaining its integrity as a uniquely African artwork demonstrates its enduring significance. Its treatment of themes such as sacrifice, duty, and the relationship between community and individual continues to resonate in post-apartheid South Africa and beyond.

Conclusion

"The Sinking of the Mendi" stands as a masterpiece of South African literature, demonstrating how poetry can serve both as historical commemoration and as a vehicle for sophisticated political and theological reflection. Mqhayi's achievement lies not only in his elegant synthesis of different cultural and religious traditions but in his ability to create a work that speaks powerfully to both the specific historical moment of the Mendi disaster and to broader questions of sacrifice, colonialism, and redemption that continue to resonate today.

The poem's enduring power derives from its ability to transform a specific historical tragedy into a meditation on universal themes while maintaining its grounding in African experience and expression. In doing so, it demonstrates the capacity of African literature to speak to both local and universal concerns, creating a work of lasting significance that continues to reward careful study and reflection.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!