Yr Afon (Welsh)

Watcyn Wyn

1844 to 1905

Yn ei gwely—byth yn cysgu,

Ar ei gyrfa—byth yn gorphwys:

Yn y ffynon—byth yn tarddu,

Yn yr aber—byth yn arllwys:

Gloewi ei drych,

A chânu 'n llon,

O grych i grych,

O dòn i dòn:

Rhwng y ceryg, dros y gro,

Byth yn troi 'n ol yn y tro:

Wedi dysgu ei thònau gwan,

I beidio aros yn un man:

Casglu nerth pwy bella teithia,

Penderfyniad yn y troion;

A diwydrwydd, a glanweithdra,

Yn ei thònau 'n wersi gloewon.

Watcyn Wyn's Yr Afon

Watcyn Wyn’s Yr Afon (The River) is a lyrical meditation on motion, persistence, and the inexorable passage of time, rendered with a simplicity that belies its profound philosophical depth. Written in Welsh, the poem draws upon the natural world to explore themes of labor, purity, and the ceaseless forward march of existence. Through its vivid imagery and rhythmic cadence, Yr Afon transcends mere description, becoming a metaphysical reflection on life’s unyielding progression. This essay will examine the poem’s historical and cultural context, its literary devices, thematic concerns, and emotional resonance, while also considering its place within the broader tradition of nature poetry.

Historical and Cultural Context

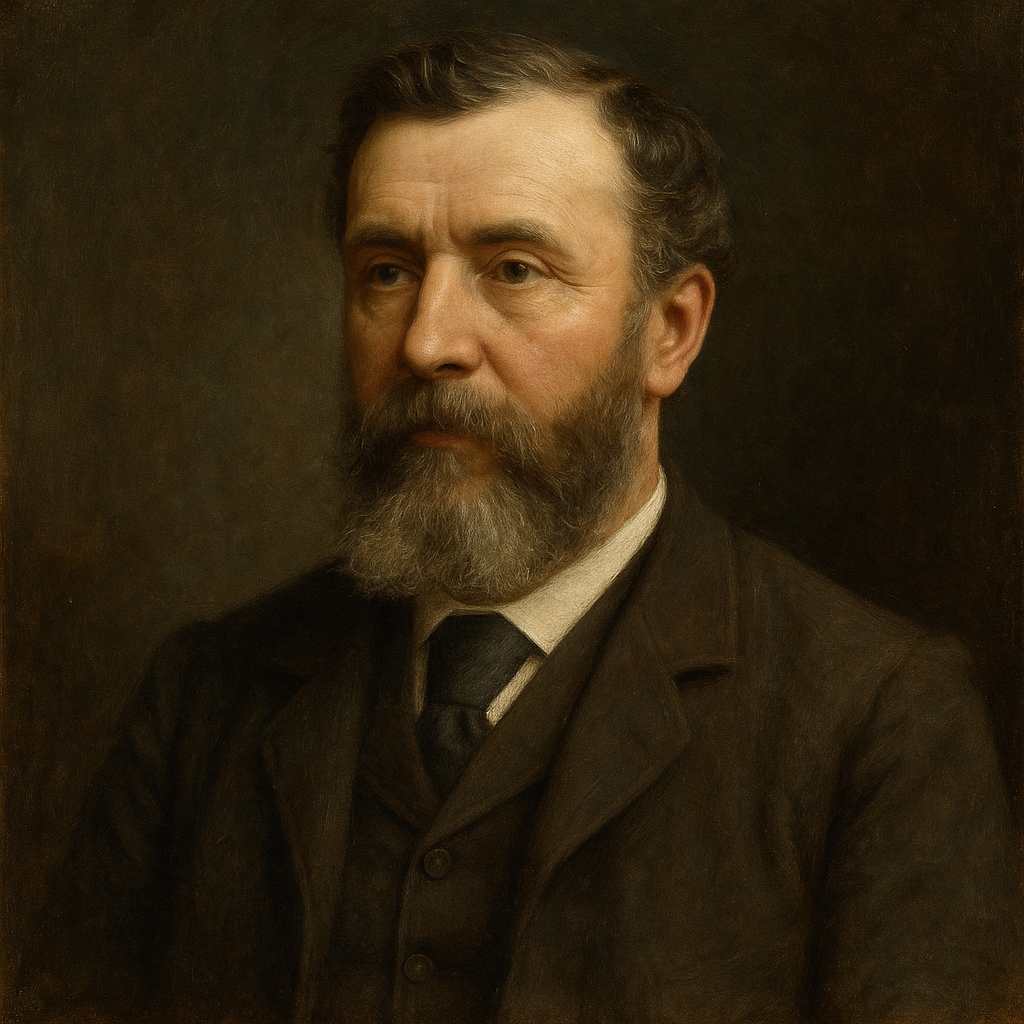

Watcyn Wyn (1844–1905), born Watkin Hezekiah Williams, was a Welsh poet, schoolmaster, and hymnist whose work emerged during a period of significant cultural and linguistic revival in Wales. The 19th century saw a resurgence of interest in Welsh literature, partly in response to the pressures of industrialization and Anglicization. Wyn’s poetry often reflects a deep engagement with Welsh identity, landscape, and moral philosophy, blending Romantic sensibilities with a didactic impulse.

Yr Afon fits within the long tradition of Welsh nature poetry, which includes figures such as Dafydd ap Gwilym and later R. S. Thomas. However, unlike the medieval bards who often celebrated nature’s beauty in ornate terms, Wyn’s poem is more contemplative, focusing on the river as a symbol of relentless movement and moral instruction. The poem’s emphasis on perseverance (Penderfyniad yn y troion—"determination in its turns") may also reflect the Victorian ethos of industriousness, yet it avoids overt moralizing, instead allowing the river’s natural behavior to serve as its own lesson.

Literary Devices and Structure

Though the poem’s rhyme scheme will not be analyzed in detail, its rhythmic structure is worth noting. The lines are short and flowing, mimicking the river’s perpetual motion. The repetition of byth yn ("never") in the opening lines creates a hypnotic effect, reinforcing the river’s eternal restlessness:

Yn ei gwely—byth yn cysgu,

Ar ei gyrfa—byth yn gorphwys:

(In its bed—never sleeping,

On its course—never resting:)

This anaphoric structure establishes the river as a tireless force, a motif sustained throughout the poem. The parallelism in Gloewi ei drych, / A chânu 'n llon ("Brightening its mirror, / And singing joyfully") further enhances the sense of rhythmic continuity.

Wyn employs rich visual and auditory imagery to evoke the river’s journey. The crych i grych ("ripple to ripple") and dòn i dòn ("wave to wave") suggest both the physical undulations of water and the passage of time. The river’s movement over stones (rhwng y ceryg) and gravel (dros y gro) is tactile, grounding the poem in sensory experience while also symbolizing life’s obstacles.

Metaphorically, the river is both a mirror (Gloewi ei drych) and a teacher (wersi gloewon—"bright lessons"). Its clarity and constancy become moral exemplars, a common trope in Romantic and Victorian nature poetry. Yet Wyn avoids sentimentality; the river is not merely pretty but purposeful, gathering strength (Casglu nerth) as it travels further.

Themes and Philosophical Undercurrents

1. The Inevitability of Motion

The river’s defining characteristic is its refusal to stagnate. It never sleeps, never rests, never stops pouring into the estuary (Yn yr aber—byth yn arllwys). This relentless movement mirrors Heraclitus’ famous dictum that one cannot step into the same river twice—a philosophical meditation on flux. Wyn’s river is not just water in motion but an emblem of time itself, always advancing, never turning back (Byth yn troi 'n ol yn y tro).

2. Labor and Purity

The poem subtly aligns the river’s journey with virtues of diligence (diwydrwydd) and cleanliness (glanweithdra). Unlike human labor, which may be tainted by fatigue or corruption, the river’s work is pure, its lessons gloewon ("bright" or "clear"). This purity may reflect a Victorian idealization of nature as morally instructive, yet Wyn’s treatment feels less prescriptive than observational. The river does not preach; it simply is, and in its being, it teaches.

3. The Illusion of Permanence

The river’s waves (thònau gwan—"weak waves") learn not to linger (I beidio aros yn un man). This line carries existential weight: nothing in life remains static, and even the most fleeting elements must move forward. The river’s strength comes not from resistance but from surrender to its course, a Stoic acceptance of fate.

Comparative Perspectives

Yr Afon invites comparison with other river poems, such as Tennyson’s The Brook ("For men may come and men may go, / But I go on forever"). Both poems personify waterways as eternal travelers, but where Tennyson’s brook is chatty and self-assured, Wyn’s river is more solemn, its lessons embedded in silence.

A more striking parallel exists with the poetry of R. S. Thomas, who also used Welsh landscapes to explore metaphysical questions. Thomas’ The Moor presents nature as austere and indifferent, whereas Wyn’s river, though relentless, is not unkind—it sings (chânu 'n llon) as it flows.

Emotional Resonance

The poem’s emotional power lies in its quiet persistence. There is joy in the river’s song, but also inevitability, even melancholy. The river cannot stop, cannot rest—its beauty is inseparable from its burden. For the reader, this evokes both admiration and a faint unease: are we, like the river, compelled forward without reprieve?

Yet there is comfort in the river’s clarity. Its wersi gloewon suggest that movement itself is a form of wisdom. In a world of uncertainty, the river’s constancy is almost reassuring—it will not turn back, and neither, ultimately, can we.

Conclusion

Yr Afon is a masterful synthesis of natural observation and philosophical inquiry. Watcyn Wyn transforms a simple river into a vessel for profound meditation on time, labor, and the necessity of forward motion. The poem’s brilliance lies in its restraint: it does not shout its themes but lets them flow, like water over stones, leaving the reader with a sense of both transience and eternal recurrence.

In an age of rapid industrialization and cultural change, Wyn’s river stands as a quiet counterpoint—a reminder that some forces remain untamed, some lessons timeless. The poem endures not just as a piece of Welsh literature but as a universal reflection on the currents that shape our lives.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!