Richard Cory

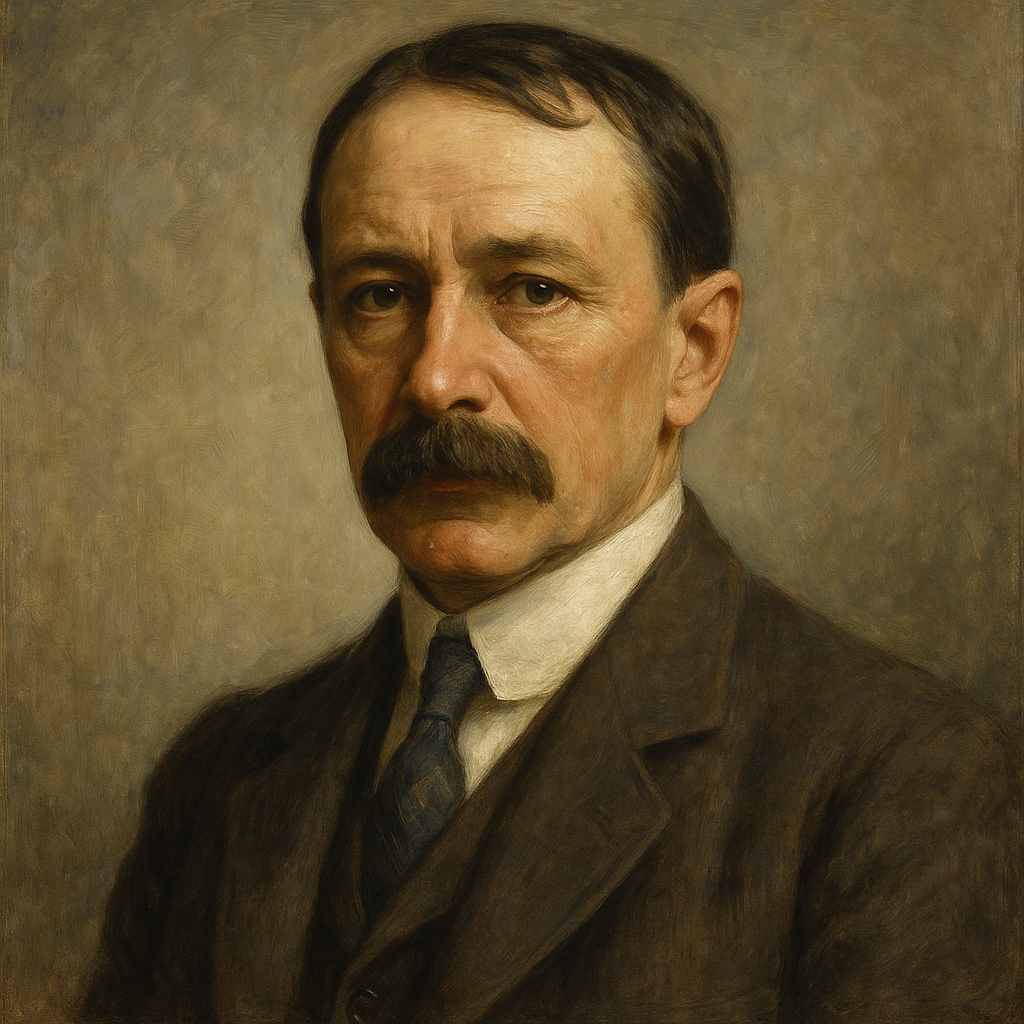

Edwin Arlington Robinson

1869 to 1935

Whenever Richard Cory went down town,

We people on the pavement looked at him:

He was a gentleman from sole to crown,

Clean favored, and imperially slim.

And he was always quietly arrayed,

And he was always human when he talked;

But still he fluttered pulses when he said,

"Good-morning," and he glittered when he walked.

And he was rich—yes, richer than a king—

And admirably schooled in every grace:

In fine, we thought that he was everything

To make us wish that we were in his place.

So on we worked, and waited for the light,

And went without the meat, and cursed the bread;

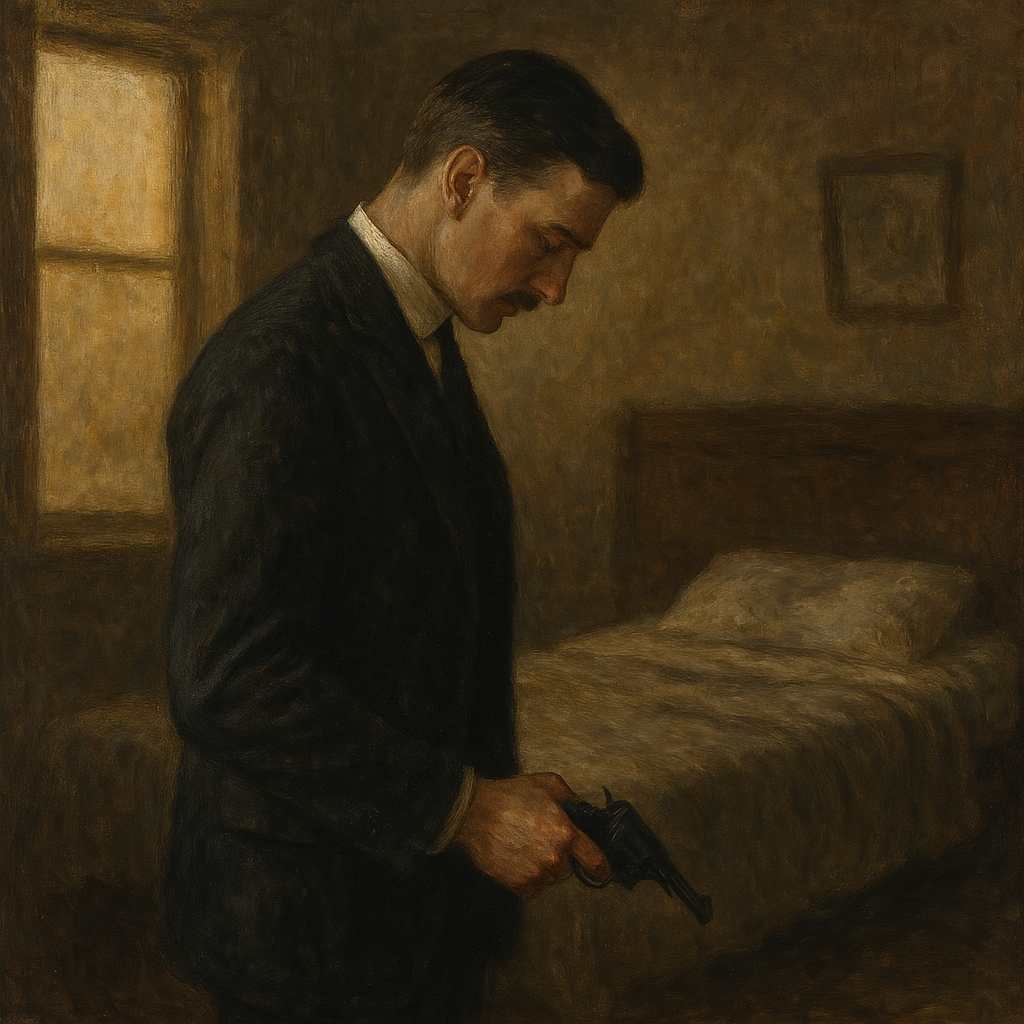

And Richard Cory, one calm summer night,

Went home and put a bullet through his head.

Edwin Arlington Robinson's Richard Cory

Few poems in American literature have achieved the enduring resonance and interpretive richness of Edwin Arlington Robinson’s “Richard Cory.” First published in 1897 in The Children of the Night, this brief yet haunting narrative has captivated readers for over a century, inviting reflection on the paradoxes of wealth, the illusions of happiness, and the silent agonies that lurk behind polished facades. Robinson’s poem, deceptively simple in structure and language, delivers a profound commentary on the human condition, the social hierarchies of his era, and the enduring mysteries of the individual psyche.

This essay embarks on an in-depth exploration of “Richard Cory,” situating it within its historical and cultural context, examining its literary devices, themes, and emotional impact, and drawing upon biographical and philosophical insights to illuminate its enduring power. Through a close reading and contextual analysis, we will uncover the layers of meaning that make this poem a touchstone for both scholarly inquiry and personal reflection.

Historical and Cultural Context

The Gilded Age and Its Discontents

“Richard Cory” emerged at the tail end of the 19th century, a period often referred to as the Gilded Age in American history. This era, spanning roughly from the 1870s to the early 1900s, was marked by rapid industrialization, economic expansion, and the conspicuous accumulation of wealth by a select few. Cities burgeoned, fortunes were made and lost overnight, and social divisions deepened between the affluent elite and the struggling working class.

The poem’s setting—a small American town with “people on the pavement” gazing at a solitary, affluent figure—mirrors the social stratification and longing that characterized the period. The townspeople’s envy of Richard Cory’s apparent perfection reflects the era’s obsession with material success and the belief that wealth equated to happiness and fulfillment. Yet, beneath the surface, the Gilded Age was also a time of anxiety, insecurity, and disillusionment. Economic depressions, labor unrest, and the growing awareness of inequality fueled a sense of malaise that found expression in the literature of the time.

Robinson’s Personal Lens

Edwin Arlington Robinson’s own life was deeply entwined with the themes of loss, disappointment, and the gap between outward appearance and inner reality. Born into a prosperous family in Maine, Robinson witnessed the decline of his family’s fortunes and the personal tragedies of his brothers, experiences that profoundly shaped his poetic vision. His fictional “Tilbury Town,” the setting for many of his poems, is a thinly veiled version of his hometown, Gardiner, Maine—a place marked by both community and isolation, prosperity and despair.

Robinson’s poetry often gives voice to the marginalized, the disillusioned, and the misunderstood—figures who, like Richard Cory, are defined as much by what they conceal as by what they reveal. In this sense, the poem is not only a product of its historical moment but also a deeply personal meditation on the limits of empathy and the dangers of superficial judgment.

Literary Devices and Techniques

Narrative Perspective and Voice

One of the most striking features of “Richard Cory” is its use of the collective first-person plural: “we people on the pavement.” This communal voice serves several functions. It establishes a clear division between the observer and the observed, reinforcing the social distance between Cory and the townspeople. It also invites the reader to identify with the crowd, to share in their admiration, envy, and ultimately, their shock.

The narrative voice is characterized by a tone of awe and deference. Phrases like “gentleman from sole to crown,” “imperially slim,” and “richer than a king” elevate Cory to a near-mythic status. Yet, this reverence is subtly undercut by the ordinariness of the townspeople’s lives—“we worked, and waited for the light, / And went without the meat, and cursed the bread”—a juxtaposition that heightens the poem’s emotional impact.

Imagery and Symbolism

Robinson’s imagery is precise and evocative. Richard Cory is described as “clean favored,” “quietly arrayed,” and “glittered when he walked.” These images not only convey his physical attractiveness and elegance but also suggest a kind of untouchable, almost otherworldly quality. The word “glittered,” in particular, connotes both allure and a certain coldness, hinting at the distance between Cory and those who admire him.

The poem’s final image—Cory returning home “one calm summer night” to “put a bullet through his head”—is all the more shocking for its understatement. The calmness of the night contrasts with the violence of the act, and the abruptness of the ending leaves the reader reeling, forced to confront the chasm between appearance and reality.

Irony and Withholding

Irony is the poem’s most potent device. The entire narrative builds toward an expectation of fulfillment and contentment, only to subvert it in the final line. The townspeople, and by extension the reader, are led to believe that Cory’s life is enviable in every respect. The revelation of his suicide is not only unexpected but also unexplained, leaving the poem’s central mystery unresolved.

Robinson’s technique of withholding—providing just enough detail to provoke curiosity but not enough to satisfy it—invites multiple interpretations. We are never given access to Cory’s inner life; his motivations remain opaque. This deliberate ambiguity is both a source of the poem’s power and a commentary on the limits of human understanding.

Diction and Tone

The diction of “Richard Cory” is notable for its restraint and clarity. Robinson eschews ornamentation in favor of directness, allowing the emotional weight of the story to emerge naturally. The tone is respectful, even reverential, but never sentimental. The poem’s language is accessible, yet its implications are profound, demonstrating Robinson’s mastery of understatement and suggestion.

Themes

The Illusion of Happiness

At its core, “Richard Cory” is a meditation on the illusion of happiness. The townspeople view Cory as the embodiment of success—wealthy, graceful, admired, and seemingly content. Their envy is palpable: “we thought that he was everything / To make us wish that we were in his place.” Yet, this perception is revealed to be tragically mistaken. Cory’s suicide exposes the hollowness of external markers of happiness and the dangers of equating material success with inner fulfillment.

This theme resonates powerfully in the context of the American Dream, a cultural ideal that equates prosperity with happiness and self-worth. Robinson’s poem challenges this narrative, suggesting that the pursuit of wealth and status may mask, rather than resolve, deeper existential anxieties.

Social Class and Alienation

The poem’s depiction of class divisions is subtle but pervasive. Cory’s wealth and refinement set him apart from the townspeople, who “went without the meat, and cursed the bread.” The physical and psychological distance between Cory and the community is reinforced by the repeated use of “we” and “he,” underscoring the impossibility of genuine connection.

Yet, Cory’s apparent perfection is itself a form of isolation. His every action is scrutinized, his humanity reduced to a series of admired traits. The poem suggests that privilege can be as much a burden as a blessing, fostering loneliness and alienation even in the midst of admiration.

The Limits of Empathy and Perception

“Richard Cory” is also a meditation on the limits of empathy. The townspeople observe Cory from a distance, constructing an image of his life based on outward appearances. Their inability to perceive his inner struggles is both a personal and a collective failing, a reminder of the dangers of superficial judgment.

The poem’s refusal to provide an explanation for Cory’s suicide is a powerful statement about the unknowability of others. We are left, like the townspeople, to grapple with the mystery of his despair, forced to acknowledge the limits of our understanding.

The Tragedy of Unfulfilled Longing

The townspeople’s longing for Cory’s life is a recurring motif. Their daily struggles—working, waiting for the light, going without—are contrasted with Cory’s apparent ease. Yet, the poem suggests that longing itself can be a source of suffering, blinding us to the complexities of others’ lives and to the possibilities of our own.

Emotional Impact

The Shock of the Final Line

The emotional impact of “Richard Cory” is concentrated in its final line, which arrives with the force of a thunderclap: “And Richard Cory, one calm summer night, / Went home and put a bullet through his head.” The abruptness of the revelation, following three stanzas of admiration and envy, is both devastating and thought-provoking.

This ending forces the reader to reevaluate everything that has come before, to question the assumptions and judgments that have shaped our understanding of Cory. The poem’s emotional power lies in its ability to provoke empathy, confusion, and self-reflection, leaving us unsettled and haunted by the mysteries of the human heart.

Universal Resonance

Part of the poem’s enduring appeal is its universality. The experience of envying others, of assuming that those who seem fortunate are in fact happy, is a common human failing. Robinson’s poem gives voice to this tendency, only to expose its dangers and limitations. The emotional resonance of “Richard Cory” lies in its capacity to evoke both sympathy for its protagonist and self-recognition in its readers.

Comparative Analysis and Literary Legacy

Robinson and His Contemporaries

Robinson’s approach to character and narrative distinguishes him from many of his contemporaries. While poets like Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson explored the self in expansive or idiosyncratic ways, Robinson’s focus is on the social self—individuals defined by their relationships to community, class, and expectation. In this sense, “Richard Cory” anticipates the psychological realism of later poets such as Robert Frost and the narrative experimentation of modernists like T. S. Eliot.

The poem’s influence can be seen in a wide range of subsequent literature. Its central conceit—the hidden despair of the privileged—has inspired countless reinterpretations, from Simon & Garfunkel’s song “Richard Cory” to contemporary novels and films exploring similar themes.

Biographical Insights

Robinson’s own experiences of loss, disappointment, and social observation inform the poem’s perspective. His acute awareness of the gap between appearance and reality, shaped by personal tragedy and the decline of his family’s fortunes, lends authenticity to his portrayal of Cory’s isolation. The poet’s lifelong fascination with the complexities of human motivation and the ambiguities of social perception is evident in every line.

Philosophical Perspectives

From a philosophical standpoint, “Richard Cory” can be read as an exploration of existential themes. The poem confronts the absurdity of existence—the possibility that a life outwardly marked by success and admiration may nonetheless be devoid of meaning or satisfaction. Cory’s suicide is an act that defies explanation, a gesture that exposes the limits of reason and the unpredictability of human desire.

The poem also engages with questions of authenticity and self-knowledge. The townspeople’s projections onto Cory reflect the human tendency to construct narratives about others based on incomplete information. Robinson’s refusal to resolve the poem’s central mystery is a philosophical statement in itself, a recognition of the irreducible complexity of the self.

Literary Devices: A Closer Look

Metonymy and Synecdoche

Robinson employs metonymy and synecdoche to great effect. Cory is described not as a fully realized individual but as a collection of attributes—“gentleman from sole to crown,” “imperially slim,” “quietly arrayed.” These descriptions reduce him to a set of symbols, reinforcing the townspeople’s (and the reader’s) tendency to see him as an ideal rather than a person.

Allusion and Intertextuality

The poem’s references to royalty (“richer than a king,” “imperially slim”) evoke a tradition of literary and cultural allusion, situating Cory within a lineage of tragic figures whose outward greatness conceals inner turmoil. This intertextual dimension enriches the poem’s meaning, inviting comparisons to figures such as Hamlet or Gatsby—characters whose public personas mask private suffering.

Repetition and Parallelism

The poem’s use of repetition—“And he was always...,” “And he was rich...”—creates a sense of ritual observation, as if the townspeople are reciting a litany of Cory’s virtues. This parallelism underscores the monotony of their own lives and the constancy of their admiration, while also hinting at the emptiness of such repetitive longing.

The Poem’s Structure and Its Effects

Although the poem’s technical structure is not the focus of this analysis, it is worth noting how its organization contributes to its impact. Each stanza builds upon the last, layering detail upon detail, until the final stanza abruptly shatters the illusion. The poem’s progression from admiration to shock mirrors the psychological journey of the reader, drawing us into the collective experience of the townspeople before confronting us with the limits of our understanding.

The Enduring Relevance of “Richard Cory”

Contemporary Resonance

More than a century after its publication, “Richard Cory” remains strikingly relevant. In an age of social media, where curated images of happiness and success abound, the poem’s warning against superficial judgment is more urgent than ever. The tendency to equate outward appearance with inner well-being persists, often with tragic consequences.

The poem also speaks to contemporary concerns about mental health, loneliness, and the pressures of societal expectation. Cory’s suicide, unexplained and unexpected, is a reminder of the hidden struggles that can afflict even those who seem most fortunate.

Educational and Cultural Impact

“Richard Cory” is a staple of American literary education, frequently anthologized and analyzed in classrooms across the country. Its accessibility and depth make it an ideal entry point for discussions of poetry, narrative perspective, and social critique. The poem’s capacity to provoke debate and reflection ensures its continued vitality in both academic and popular contexts.

Conclusion: The Mystery and Power of “Richard Cory”

“Richard Cory” endures because it refuses easy answers. Its brilliance lies in its capacity to evoke empathy, provoke self-examination, and illuminate the complexities of human desire and perception. Robinson’s poem is a masterclass in narrative economy, psychological insight, and emotional resonance, offering a portrait of a man—and a community—defined as much by what is hidden as by what is revealed.

In reading “Richard Cory,” we are invited to confront our own assumptions, to question the stories we tell about others and ourselves, and to recognize the profound mysteries that underlie even the most ordinary lives. The poem’s final, devastating line echoes across the decades, a testament to the enduring power of poetry to unsettle, to enlighten, and to move.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!