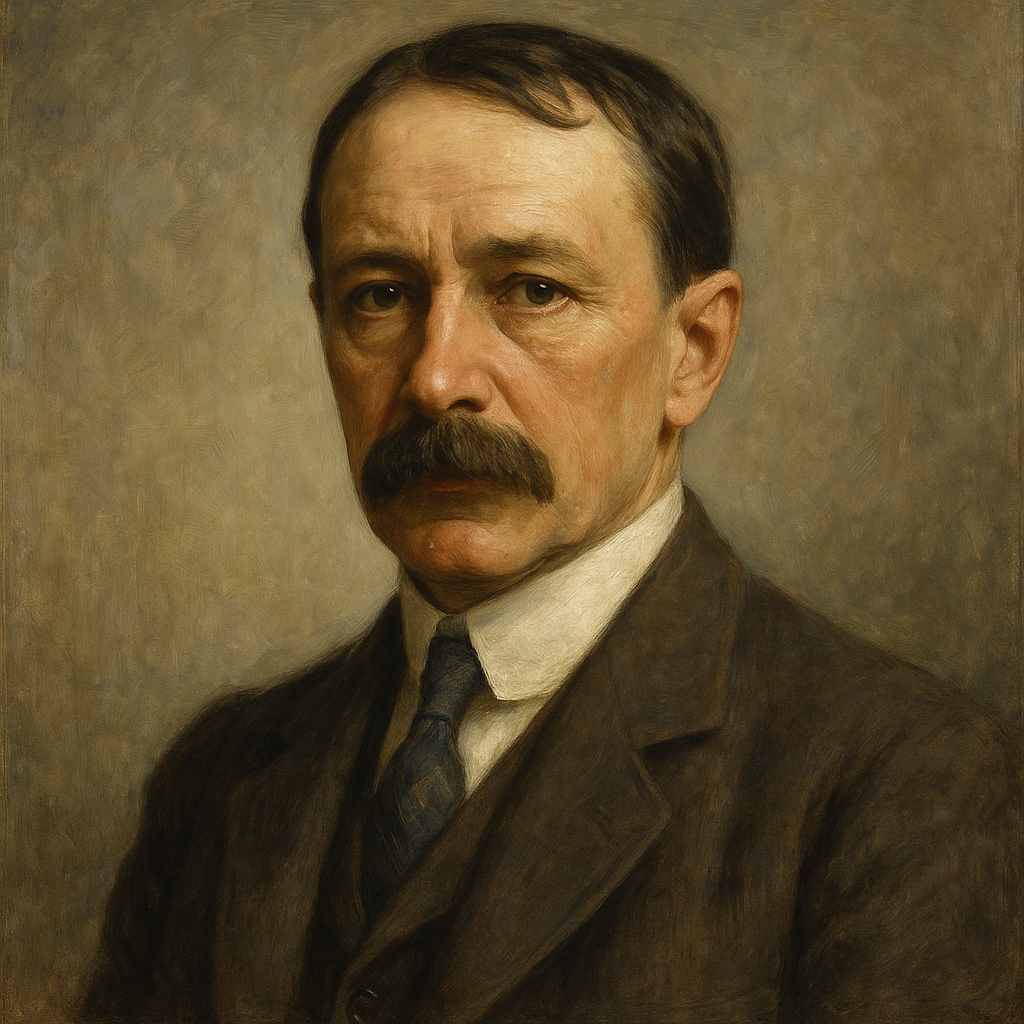

1 Poems by Edwin Arlington Robinson

1869 - 1935

Edwin Arlington Robinson Biography

Edwin Arlington Robinson stands as one of the most distinctive and influential voices in American poetry. Renowned for his psychologically nuanced portraits, precise craftsmanship, and unflinching explorations of the human condition, Robinson’s work bridges the 19th and 20th centuries, offering both the rigor of tradition and the insights of modernity. His journey from the small towns of Maine to the literary heights of New York is a tale of perseverance, artistry, and quiet revolution—a story as compelling as the characters that populate his verse.

Early Life: Shadows and Promise in Maine

Edwin Arlington Robinson was born on December 22, 1869, in the village of Head Tide, Maine, the third son of Edward and Mary Elizabeth (Palmer) Robinson. His family soon moved to Gardiner, a bustling mill town on the Kennebec River, which would later inspire the fictional Tilbury Town, the setting for many of his poems. The Robinson household was comfortable, even prosperous, but not without its shadows. Edwin’s father was a successful timber merchant, but the family’s fortunes would ultimately decline, mirroring the fates of many of the poet’s characters.

Robinson’s childhood was marked by a sense of isolation. He was a quiet, introspective boy, more interested in books than in the rough-and-tumble games of other children. His mother, cultured and sensitive, encouraged his literary interests, while his father remained distant. The poet’s name itself was the result of chance: his parents, expecting a girl, delayed naming him until a visiting stranger from Arlington, Massachusetts, suggested “Arlington.” The name “Edwin” was added later, reportedly drawn from a hat.

Tragedy would haunt Robinson’s early years. His eldest brother, Dean, succumbed to addiction; his middle brother, Herman, suffered a failed marriage and early death. These family misfortunes deeply affected Robinson, shaping the somber tone and themes of loss, regret, and failed aspirations that pervade his poetry.

Education and Awakening: Harvard and Beyond

Robinson’s formal education began in Gardiner, where he proved a diligent if unremarkable student. In 1891, he enrolled at Harvard University as a special student, attending for two years without pursuing a degree. At Harvard, Robinson encountered the intellectual ferment of the late 19th century, reading widely in literature and philosophy, and publishing his first poems in the Harvard Advocate. These years were formative, exposing him to the literary traditions and innovations that would inform his mature style.

Yet, Harvard was not a period of unalloyed happiness. Robinson was shy, self-conscious, and often lonely. The death of his father and the family’s declining fortunes forced him to return to Maine in 1893, where he found his family in disarray and his own prospects uncertain. The sense of being an outsider—intellectually ambitious but emotionally adrift—became a defining feature of his poetry.

The Struggling Poet: Early Career and First Publications

Back in Gardiner, Robinson faced years of poverty and obscurity. He tried his hand at farming and various odd jobs, but his true vocation was poetry. In 1896, he privately published his first book, The Torrent and the Night Before, at his own expense, hoping to surprise his ailing mother. Tragically, she died of diphtheria just days before the copies arrived. This early loss, compounded by the deaths of his brothers, deepened the melancholy that would become his poetic signature.

Robinson’s second collection, The Children of the Night (1897), fared little better commercially, but it contained some of his most enduring poems, including “Luke Havergal” and “Richard Cory.” The latter, a masterful portrait of a wealthy man’s hidden despair, would become one of the most anthologized poems in American literature.

Despite these early setbacks, Robinson’s work began to attract the attention of discerning readers. Among them was Kermit Roosevelt, son of President Theodore Roosevelt, who introduced his father to Robinson’s poetry. Impressed by the poet’s talent and aware of his financial struggles, President Roosevelt arranged a sinecure for Robinson at the New York Customs House, freeing him from poverty and allowing him to focus on his writing. This act of patronage was crucial, enabling Robinson to continue his artistic pursuits during a period when many poets abandoned their craft for more secure livelihoods.

New York and Literary Emergence

In 1897, Robinson moved to New York City, seeking both anonymity and opportunity. The city, with its teeming crowds and vibrant artistic scene, provided a stark contrast to the insular world of Gardiner. Robinson lived modestly, often relying on the support of friends, but he gradually established himself within the literary community. He cultivated friendships with other writers, artists, and intellectuals, and began to publish more regularly.

The publication of The Town Down the River (1910) and The Man Against the Sky (1916) marked turning points in Robinson’s career. The latter collection, in particular, brought him critical acclaim, showcasing his mastery of the dramatic lyric and his ability to probe the complexities of the human psyche. Robinson’s poetry, with its precise diction, structured stanzas, and psychological depth, stood apart from the prevailing currents of late Romanticism, introducing a new realism and moral seriousness to American verse.

Major Works: Portraits of the Human Condition

The Tilbury Town Poems

Robinson’s most celebrated poems are set in the fictional Tilbury Town, a thinly veiled version of Gardiner. In these works, he created a gallery of memorable characters—Richard Cory, Miniver Cheevy, Mr. Flood, and others—each grappling with disappointment, loneliness, or existential despair. These poems, though often brief and formally traditional, offer profound insights into the human condition.

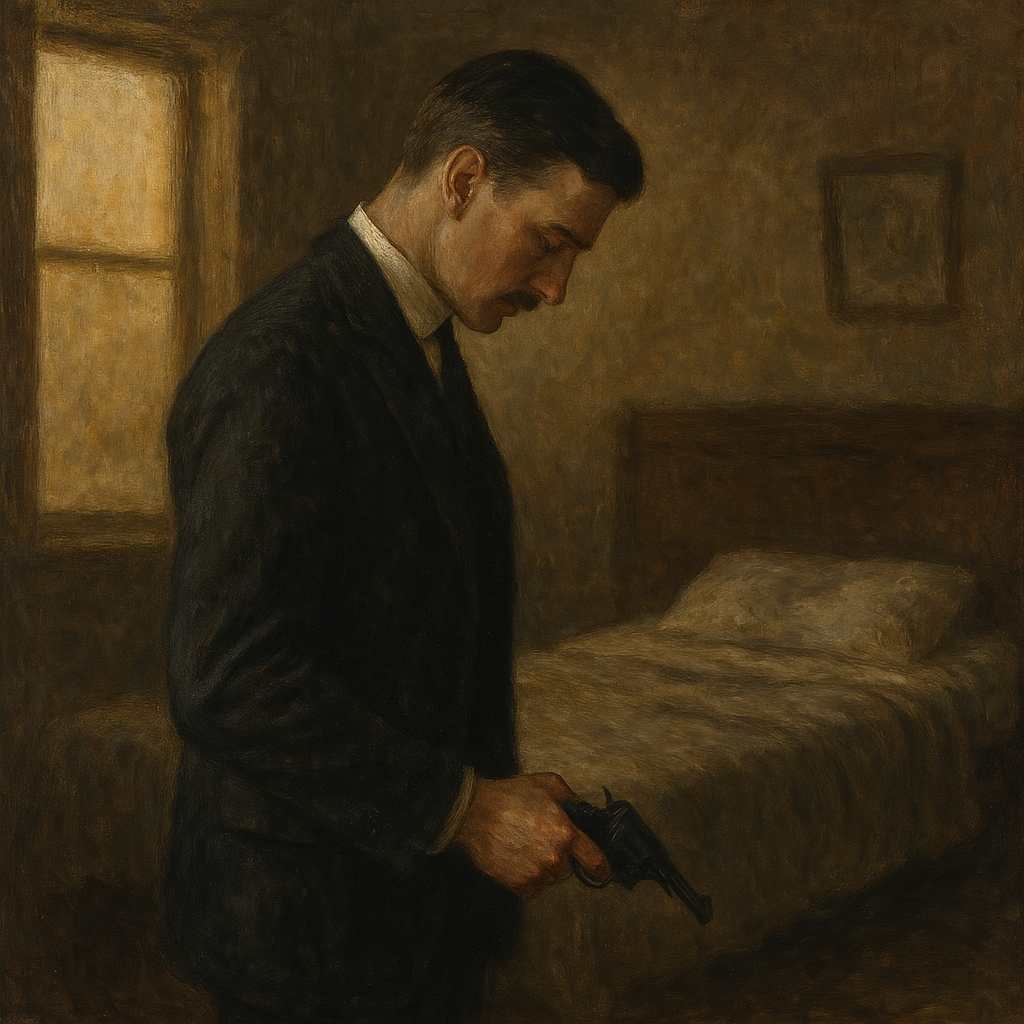

- “Richard Cory”: Perhaps Robinson’s most famous poem, “Richard Cory” tells the story of a wealthy, admired man who, despite his apparent success, takes his own life. The poem’s understated irony and psychological subtlety have made it a staple of American literature, prompting endless interpretations of its enigmatic protagonist.

- “Miniver Cheevy”: This portrait of a dreamer, nostalgic for a romanticized past, captures the tension between aspiration and reality. Miniver’s comic self-pity and escapism are rendered with both sympathy and gentle mockery, illustrating Robinson’s nuanced approach to character.

- “Mr. Flood’s Party”: In this later poem, Robinson explores the loneliness of old age through the figure of Eben Flood, who toasts himself in solitude. The poem’s blend of humor and pathos exemplifies Robinson’s ability to evoke empathy for even the most marginalized figures.

Narrative Poems and Arthurian Trilogy

In the second phase of his career, Robinson turned to longer narrative poems, often drawing on classical and Arthurian legends. His trilogy—Merlin (1917), Lancelot (1920), and Tristram (1927)—reimagines the stories of King Arthur’s court, using them as vehicles for psychological and philosophical exploration.

- “Merlin”: A study of romantic love and disillusionment, “Merlin” blends mythic grandeur with modern skepticism.

- “Lancelot”: This poem examines the figure of the doubter, torn between faith and reason.

- “Tristram”: Widely regarded as Robinson’s most successful long poem, “Tristram” achieved both critical and popular acclaim, winning the Pulitzer Prize and becoming a rare best-selling book-length poem in the 20th century.

Robinson’s narrative poems are notable for their psychological complexity, moral ambiguity, and formal innovation. While some critics have found these works diffuse or lacking the concentrated power of his shorter lyrics, others have praised their ambition and depth.

Other Notable Works

Robinson published over twenty books of poetry, including:

- The Torrent and the Night Before (1896)

- The Children of the Night (1897)

- Captain Craig and Other Poems (1902)

- The Man Against the Sky (1916)

- The Three Taverns (1920)

- Avon’s Harvest (1921)

- The Man Who Died Twice (1924)

- Amaranth (1934)

- King Jasper (1935)

His collected poems, published in 1921, won his first Pulitzer Prize. He would go on to win two more Pulitzers, for The Man Who Died Twice (1925) and Tristram (1928), a testament to his stature in American letters.

Style and Themes: The Art of Withholding

Robinson’s poetry is characterized by its formal precision, understated diction, and psychological insight. He favored traditional verse forms—sonnets, quatrains, blank verse—but infused them with modern sensibilities. His language is plain but exact, eschewing ornament for clarity and force.

A hallmark of Robinson’s style is his use of irony and the deliberate withholding of information. His poems often present enigmatic situations or characters whose motives remain obscure, inviting readers to engage actively with the text. This technique, combined with his mastery of imagery and metaphor, gives his work a depth and resonance that rewards repeated reading.

Thematically, Robinson’s poetry explores the limitations of human understanding, the loneliness of the individual, and the gap between appearance and reality. His characters are often “unheroic heroes”—derelicts, dreamers, failures—whose struggles reflect broader questions of meaning and value in modern life. Robinson’s skepticism is balanced by compassion; while he acknowledges the tragedy of unfulfilled hopes, he also affirms the dignity and resilience of the human spirit.

Critical Reception: From Obscurity to Acclaim

Robinson’s early career was marked by neglect and hardship. His first books sold poorly, and he endured years of poverty and self-doubt. Yet, as his work gained recognition, critical opinion shifted dramatically. By the 1920s, he was hailed as one of America’s greatest living poets, praised for his technical skill, psychological acuity, and moral seriousness.

His “Tilbury Town” poems, in particular, have been celebrated for their vivid characterizations and universal themes. Critics have compared Robinson’s psychological insight to that of Henry James and Edith Wharton, noting his ability to capture the complexities of motive and emotion. His mastery of form—especially the sonnet—has also earned him admiration among scholars and poets alike.

Not all assessments have been uniformly positive. Some critics have found his longer narrative poems diffuse or less compelling than his shorter works, arguing that the concentrated power of his lyrics is diluted in extended narratives. Others have noted a certain bleakness or pessimism in his worldview, though this is often tempered by irony and empathy.

Personal Life: Solitude, Friendship, and Artistic Integrity

Robinson was a private, even reclusive man, devoted to his craft and wary of the literary limelight. He never married, though he formed close relationships with several women, including the artist Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones, who attended his deathbed and memorialized him in her art. His lifelong attachment to his sister-in-law, Emma, was a source of both inspiration and sorrow; she twice rejected his marriage proposals, and her eventual return to Gardiner after her husband’s death marked a turning point in Robinson’s life.

Despite his successes, Robinson remained modest and self-effacing. He shunned publicity, preferring the company of a few trusted friends and the solitude of his study. His summers at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire provided a haven for writing and reflection, and he continued to produce poetry until his final days.

Final Years and Death

Robinson’s later years were marked by both recognition and continued productivity. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1927 and nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature four times. He continued to publish prolifically, exploring new themes and forms even as his health declined.

He died of cancer on April 6, 1935, in New York City, at the age of 65. His passing was mourned by friends, admirers, and the literary world at large. A memorial ceremony was held at Gardiner High School, and a monument was erected in his honor in Gardiner Common, funded by contributions from across the country. His childhood home in Gardiner was later designated a National Historic Landmark.

Legacy: The Enduring Voice of Tilbury Town

Edwin Arlington Robinson’s legacy endures in the richness and humanity of his poetry. His work, rooted in the particulars of small-town New England, speaks to universal experiences of longing, disappointment, and hope. He transformed the landscape of American poetry, bridging the gap between the 19th-century traditions of rationalism and the psychological realism of the modern era.

Robinson’s influence can be seen in the work of later poets, including Robert Frost and W. H. Auden, who admired his technical mastery and moral seriousness. His poems remain widely read and anthologized, their characters as vivid and compelling today as when they first appeared. The “Tilbury Town” poems, in particular, continue to resonate with readers, offering both the pleasures of narrative and the insights of psychological drama.

Critical Analysis: Strengths and Weaknesses

Robinson’s greatest strength lies in his ability to fuse traditional forms with modern themes, creating poetry that is both accessible and profound. His portraits of ordinary people—rendered with irony, compassion, and psychological depth—have set a standard for character-driven verse. His technical skill, especially in the sonnet and dramatic lyric, is widely acknowledged.

Yet, his work is not without limitations. Some critics have found his longer narrative poems less compelling, arguing that the diffuse structure and philosophical digressions weaken their impact. Others have noted a certain monotony or bleakness in his worldview, though this is often offset by humor and empathy.

Despite these criticisms, Robinson’s achievements are formidable. He revitalized American poetry at a time of transition, offering a model of artistic integrity and emotional honesty. His work continues to inspire both scholars and casual readers, a testament to his enduring vision.

Anecdotes and Personal Details

- The Accidental Name: Robinson’s unusual first names were chosen by chance, reflecting the serendipity that would characterize much of his life.

- Presidential Patronage: President Theodore Roosevelt’s intervention not only saved Robinson from poverty but also demonstrated the power of art to move even the highest offices in the land. lt’s intervention not only saved Robinson from poverty but also demonstrated the power of art to move even the highest offices in the land.

- Unrequited Love: Robinson’s lifelong attachment to Emma, his sister-in-law, and his close friendship with Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones, add a poignant dimension to his personal story.

- Solitary Genius: Despite his fame, Robinson remained a solitary figure, devoted to his craft and wary of public attention. His summers at the MacDowell Colony were among his happiest times, providing both community and creative solitude.

Conclusion

Edwin Arlington Robinson’s life and work exemplify the enduring power of poetry to illuminate the human experience. From the shadows of small-town Maine to the heights of literary acclaim, Robinson’s journey was one of quiet determination and artistic courage. His poems, with their vivid characters, psychological insight, and technical mastery, continue to speak to readers across generations. In the words of one critic, Robinson was “more artful than Hardy and more coy than Frost and a brilliant sonneteer”. His legacy is that of a poet who, in exploring the darkness, found a way to affirm the light.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Username Information

No username is open

Everything is free to use, but donations are always appreciated.

Quick Links

© 2024-2025 R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody).

All music on this site by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Attribution Requirement:

When using this music, you must give appropriate credit by including the following statement (or equivalent) wherever the music is used or credited:

"Music by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) – https://v2melody.com"

Support My Work:

If you enjoy this music and would like to support future creations, your thanks are always welcome but never required.

Thanks!