There is a tide in the affairs of men

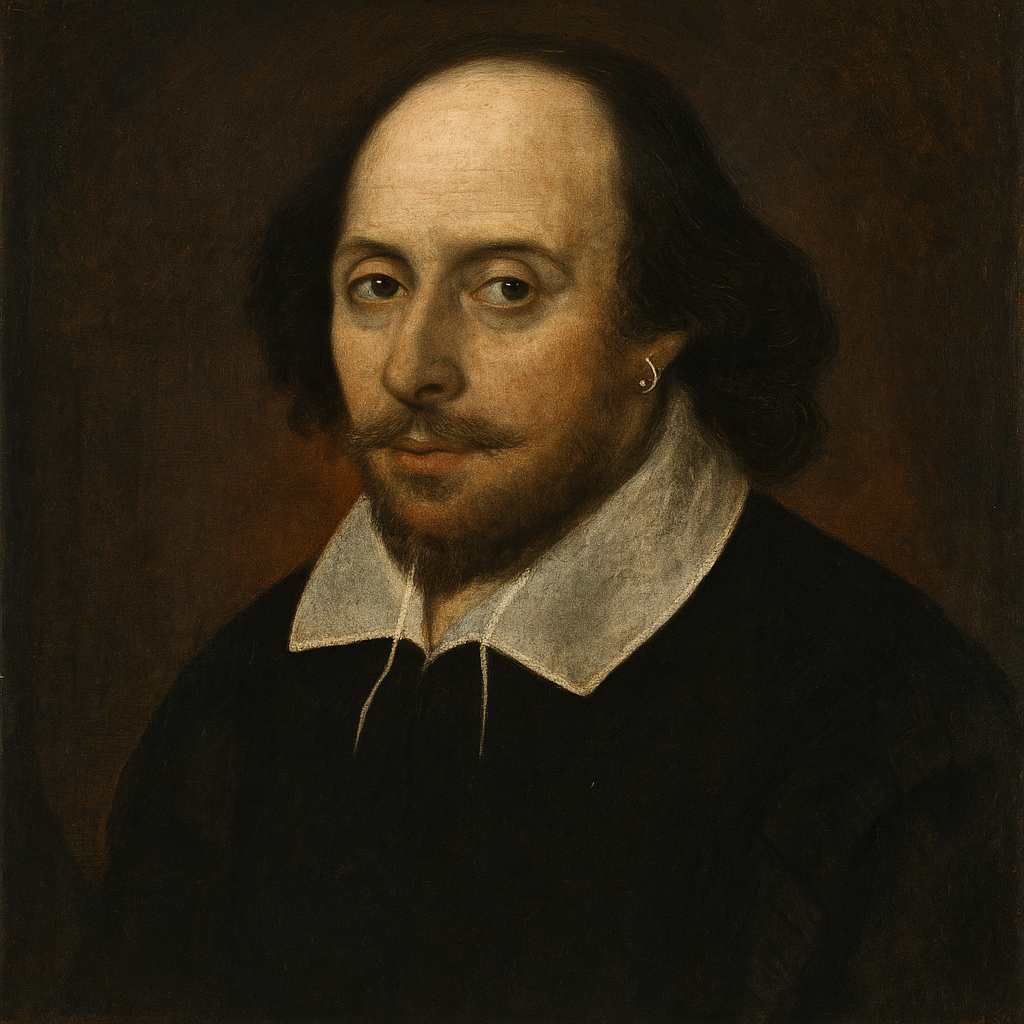

William Shakespeare

1564 to 1616

There is a tide in the affairs of men

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

On such a full sea are we now afloat,

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.

William Shakespeare's There is a tide in the affairs of men

Within the vast corpus of William Shakespeare's dramatic works, few passages capture the essence of human agency and temporal opportunity as powerfully as Brutus's meditation on the "tide in the affairs of men" from Julius Caesar. This seven-line excerpt, spoken in Act IV, Scene 3, transcends its immediate dramatic context to become one of literature's most enduring reflections on the nature of decision-making, timing, and the human condition. The passage reveals Shakespeare's masterful ability to compress profound philosophical insights into vivid, accessible imagery that continues to resonate with audiences more than four centuries after its composition.

The metaphor of life as a maritime voyage, with its tides and currents that must be navigated with skill and timing, speaks to fundamental human experiences that transcend cultural and temporal boundaries. Shakespeare's choice to place these words in the mouth of Marcus Junius Brutus, the conflicted assassin of Julius Caesar, adds layers of dramatic irony and moral complexity that illuminate both the character's psychology and the broader themes of the play. This analysis will explore how Shakespeare employs nautical imagery to examine questions of fate versus free will, the weight of moral choice, and the tragic consequences of missed opportunities.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate the depth of Shakespeare's maritime metaphor, we must first understand the cultural and historical milieu in which it was conceived. Written around 1599, Julius Caesar emerged during the height of the English Renaissance, a period when England was rapidly establishing itself as a formidable naval power. The defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 had solidified English dominance of the seas, and maritime exploration was expanding English influence across the globe. For Shakespeare's contemporary audience, references to tides, currents, and navigation would have carried immediate cultural resonance.

The Elizabethan era was characterized by a profound sense of England's destiny as a maritime nation. Explorers like Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh had become household names, and the language of seafaring permeated everyday discourse. Shakespeare himself lived in a Thames-side London where the rhythm of tides dictated much of daily life, from trade to transportation. The Globe Theatre, where Julius Caesar was likely first performed, stood within sight and sound of the Thames, its audiences intimately familiar with the ebb and flow of tidal waters.

More broadly, the Renaissance represented a period of intense interest in classical antiquity, particularly Roman history and philosophy. Shakespeare's decision to set his play in ancient Rome while employing distinctly English maritime imagery creates a deliberate anachronism that serves multiple purposes. It allows contemporary audiences to see their own world reflected in the ancient one, while also suggesting that the fundamental patterns of human behavior remain constant across time and culture. The "tide in the affairs of men" becomes not merely a Roman observation, but a universal truth applicable to all human societies.

The concept of fortune as a force that must be seized at the opportune moment was deeply embedded in Renaissance thought. Niccolò Machiavelli's influential work The Prince (1532) had popularized the notion that political success required the ability to recognize and act upon favorable circumstances. The Italian term "fortuna" encompassed both luck and the skill needed to capitalize on it, while "virtù" represented the courage and wisdom necessary to seize opportunities when they arose. Shakespeare's metaphor of the tide perfectly captures this Renaissance understanding of the dynamic relationship between chance and human agency.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Shakespeare's genius lies not merely in his choice of nautical imagery, but in how he develops and sustains this metaphor throughout the passage. The extended metaphor of life as a sea voyage creates a coherent symbolic framework that operates on multiple levels simultaneously. The "tide" represents those crucial moments when circumstances align to create opportunities for significant change or advancement. The metaphor's effectiveness stems from its basis in observable natural phenomena that audiences can readily understand and relate to.

The personification of the tide as something that "leads on to fortune" imbues natural forces with intention and purpose, suggesting that the universe itself may be conspiring to create opportunities for those wise enough to recognize them. This personification is subtly reinforced by the active voice construction, where the tide becomes the subject performing the action of leading, rather than merely existing as a passive condition.

Shakespeare's use of maritime terminology creates a lexicon of decision-making that feels both specific and universal. The phrase "taken at the flood" refers to the nautical practice of timing departures to coincide with high tide, when ships can most easily clear shallow waters and begin their journeys. This technical detail adds authenticity to the metaphor while emphasizing the crucial importance of timing in human affairs. The flood tide represents the peak moment of opportunity, when maximum advantage can be gained from natural forces.

The antithetical structure of the passage creates a powerful sense of binary choice. The consequences of seizing the tide ("leads on to fortune") are contrasted with the results of missing it ("bound in shallows and in miseries"). This stark dichotomy reflects the high-stakes nature of the decision Brutus faces, while also suggesting that life often presents us with critical junctures where the consequences of our choices are magnified far beyond their immediate context.

The imagery of being "bound in shallows" is particularly evocative, conjuring the image of a ship trapped in shallow waters, unable to reach the deep sea where great voyages are possible. The shallows represent not just failure, but a kind of living death—a state of perpetual limitation and frustrated potential. The word "bound" suggests both physical constraint and the binding nature of fate, implying that those who miss their tide become prisoners of their own inaction.

Thematic Analysis

The passage explores several interconnected themes that are central to both Julius Caesar and Shakespeare's broader dramatic concerns. The tension between fate and free will permeates every line, as Brutus grapples with the question of whether human beings can truly control their destinies or are merely subject to larger forces beyond their comprehension.

The metaphor suggests a complex relationship between determinism and agency. While the tide is a natural phenomenon beyond human control, the decision of whether to embark upon it remains firmly within human hands. This reflects Shakespeare's nuanced understanding of human psychology and moral responsibility. We are not entirely masters of our fate, the passage suggests, but neither are we entirely its victims. The crucial factor is our ability to recognize opportunity when it presents itself and to act decisively when action is required.

The theme of timing recurs throughout Shakespeare's works, from the young lovers' tragic timing in Romeo and Juliet to Hamlet's hesitation and delay. In this passage, timing becomes not merely a practical consideration but a moral imperative. The tide waits for no one, and those who hesitate risk condemning themselves to perpetual limitation. This creates a sense of urgency that drives the dramatic action forward while also commenting on the broader human condition.

The concept of fortune in the passage is particularly complex. Rather than representing mere luck or chance, fortune becomes something that must be actively pursued and seized. This aligns with Renaissance thinking about the relationship between virtue and success, where true achievement required both favorable circumstances and the courage to act upon them. The tide metaphor suggests that fortune is not randomly distributed but follows patterns that can be understood and anticipated by those with sufficient wisdom and courage.

Emotional Impact and Psychological Depth

The emotional power of the passage derives largely from its combination of cosmic scope and intimate personal stakes. Brutus speaks not as a distant philosopher but as a man facing a crucial decision that will determine not only his own fate but the fate of Rome itself. The maritime metaphor transforms what might otherwise be an abstract discussion of political strategy into something visceral and immediate.

The language creates a sense of movement and urgency that mirrors the psychological state of a person standing at a crossroads. The flowing rhythm of the lines mimics the motion of water, while the accumulating metaphors build toward a crescendo that demands resolution. This reflects Shakespeare's understanding of how great decisions are made—not through cool rational calculation alone, but through a combination of reason, intuition, and emotional commitment.

The passage also reveals the psychological burden of leadership and moral choice. Brutus must weigh not only his own interests but those of Rome itself. The metaphor of the tide suggests that such moments of decision are both rare and precious—they cannot be manufactured or summoned at will, but must be recognized and seized when they naturally occur. This creates a sense of the weight of responsibility that Brutus carries, knowing that his choice will have far-reaching consequences.

The emotional resonance is further enhanced by the implied contrast between action and inaction. The vivid imagery of being "bound in shallows and in miseries" creates a visceral sense of claustrophobia and frustration that makes the alternative—seizing the tide—seem not just attractive but necessary. This psychological dynamic drives the dramatic action while also speaking to universal human fears about missed opportunities and wasted potential.

Comparative Analysis

The tide metaphor can be productively compared to similar imagery in other works of literature, revealing both Shakespeare's originality and his participation in broader literary traditions. The classical tradition of fortune as a wheel, popularized by Boethius and later employed by Chaucer, presents a more cyclical view of human fate. Shakespeare's tide metaphor, by contrast, suggests a more linear progression where opportunities, once missed, may not return in the same form.

The passage also invites comparison with other maritime metaphors in Shakespeare's works. In The Tempest, the sea becomes a realm of transformation and renewal, where characters are shipwrecked into new understanding. In Macbeth, the metaphor of wading through blood suggests the irreversible nature of moral choices. The tide metaphor in Julius Caesar occupies a middle ground, acknowledging both the transformative potential of decisive action and the irreversible consequences of choice.

Contemporary works also employed maritime imagery to explore similar themes. Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene features numerous sea voyages that serve as metaphors for moral and spiritual journeys. John Donne's later poem "Death Be Not Proud" would use the metaphor of sleep and waking to explore themes of mortality and transformation. What distinguishes Shakespeare's usage is its integration into dramatic action and character development, making the metaphor serve not just poetic but theatrical purposes.

Philosophical Perspectives

The passage engages with several philosophical traditions that were influential during Shakespeare's time. The Stoic emphasis on accepting what cannot be changed while acting decisively on what can be controlled resonates throughout the metaphor. The tide represents those external circumstances that lie beyond human influence, while the decision to embark represents the realm of human agency where moral choice operates.

The metaphor also reflects Renaissance Humanism's emphasis on human potential and the importance of individual action in shaping history. Unlike medieval conceptions of fate that emphasized divine providence or classical notions that stressed the arbitrary nature of fortune, Shakespeare's tide metaphor suggests that opportunity and preparation can intersect in ways that allow human beings to influence their own destinies.

The passage can also be read through the lens of what would later be called existentialist philosophy. The emphasis on decisive action in the face of uncertainty, the weight of individual choice, and the consequences of hesitation all prefigure themes that would become central to existentialist thought. Brutus faces what might be termed an existential moment—a point at which he must choose his essential nature through action, knowing that this choice will define not only his future but his fundamental character.

Dramatic Function and Character Development

Within the context of Julius Caesar, the tide metaphor serves crucial dramatic functions beyond its philosophical content. It reveals Brutus's analytical nature and his tendency to intellectualize moral choices. Rather than acting on immediate emotion or simple political calculation, Brutus seeks to understand the deeper patterns that govern human affairs. This intellectual approach is both his strength and his weakness—it allows him to see the broader implications of his choices but also leads to the kind of hesitation that can prove fatal in political action.

The metaphor also foreshadows the tragic trajectory of the play. Even as Brutus speaks of seizing the tide, we sense that he may already be too late—that the flood tide of opportunity has already begun to ebb. This creates dramatic irony, as the audience recognizes that Brutus's very tendency to analyze and philosophize may prevent him from acting with the decisiveness his own metaphor demands.

The passage serves as a moment of transition in the play, marking the point where Brutus commits fully to the course of action that will ultimately lead to his destruction. The maritime metaphor transforms what might otherwise be a simple strategic discussion into a meditation on the nature of heroic action and tragic choice. It elevates Brutus from a mere political conspirator to a figure of tragic dimension, someone whose fate is bound up with larger questions about human agency and moral responsibility.

Universal Resonance and Contemporary Relevance

The enduring power of Shakespeare's tide metaphor lies in its ability to speak to universal human experiences while remaining grounded in specific, concrete imagery. Every reader can relate to the feeling of standing at a crossroads, sensing that a crucial decision must be made but uncertain about the consequences of action or inaction. The metaphor captures both the anxiety and the exhilaration of such moments, when the future seems to hang in the balance.

In contemporary contexts, the passage continues to resonate with anyone who has faced career changes, relationship decisions, or moral choices where timing seemed crucial. The metaphor has entered common usage precisely because it captures something essential about the human condition—the sense that life presents us with opportunities that must be seized when they occur or risk being lost forever.

The passage also speaks to contemporary concerns about agency and determinism in an era of global interconnection and rapid change. In a world where individual choices can have far-reaching consequences, the metaphor of the tide offers a framework for understanding how personal decisions intersect with larger historical forces. The image of being "bound in shallows" resonates particularly strongly in an age where many people feel trapped by circumstances beyond their control.

Conclusion

Shakespeare's metaphor of the tide in human affairs represents a pinnacle of poetic and philosophical achievement, combining vivid imagery with profound insight into the nature of choice, timing, and human agency. The passage succeeds on multiple levels simultaneously—as poetry, as drama, as philosophy, and as psychological observation. Its effectiveness lies not in any single element but in the masterful integration of form and content, image and meaning, specific context and universal truth.

The maritime metaphor transforms abstract questions about fate and free will into something immediate and visceral, while the dramatic context grounds these philosophical concerns in the concrete reality of political action and moral choice. The passage reveals Shakespeare's unique ability to make the cosmic personal and the personal cosmic, creating art that speaks to both the intellect and the emotions.

More than four centuries after its composition, the tide metaphor continues to offer insight into the human condition. It reminds us that while we cannot control all the circumstances that shape our lives, we retain the power to choose how we respond to those circumstances. The tide will come and go according to its own rhythms, but the decision of whether to embark upon it remains forever within human hands. In this recognition lies both the burden and the glory of human existence—the knowledge that we are, in some fundamental sense, the architects of our own destinies.

The passage stands as a testament to the enduring power of great literature to illuminate the deepest questions of human existence. Through the simple image of ships and tides, Shakespeare creates a lens through which we can examine our own lives and choices, finding in his words both challenge and consolation, both warning and encouragement. The tide continues to rise and fall, and we must still decide whether to embark upon it or remain safely—but perhaps regretfully—on shore.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

Superb performances!!!

They captures the urgency alongwith the force and power of the poem!