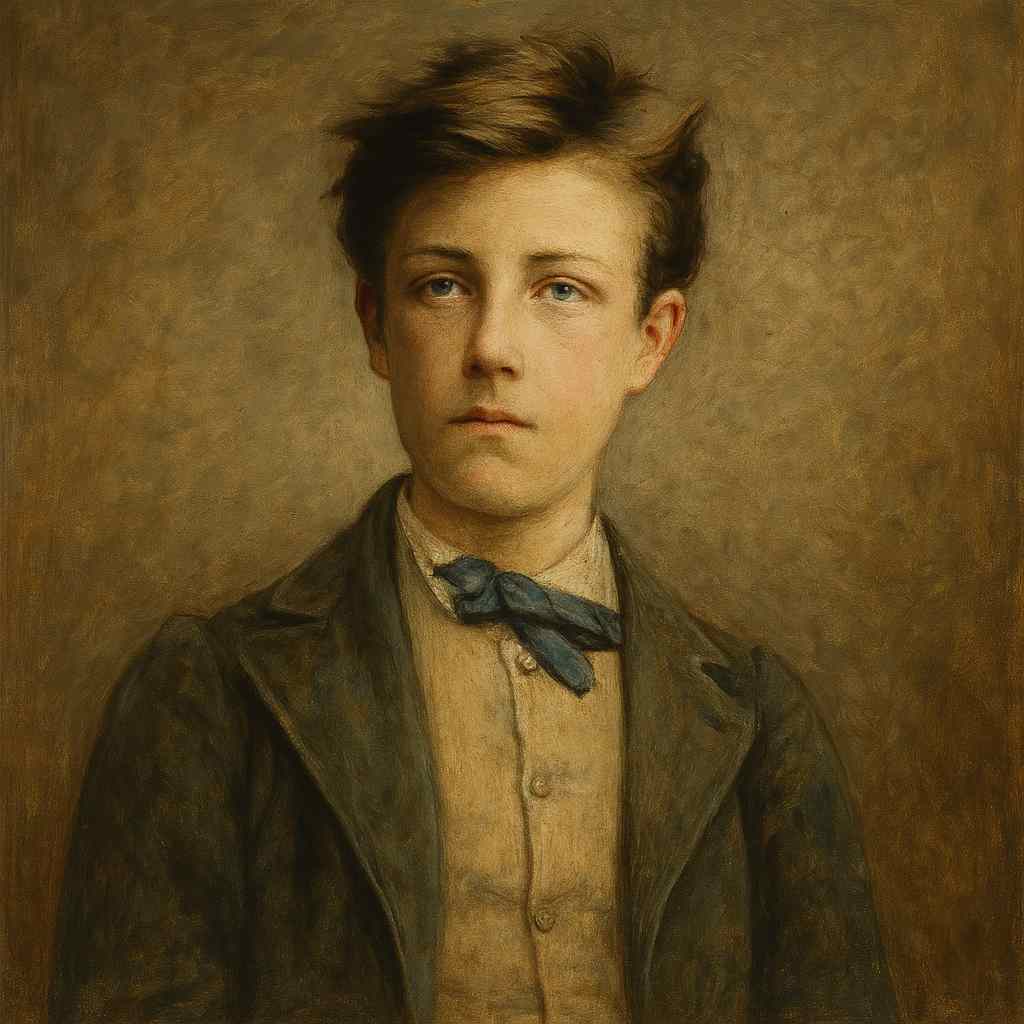

1 Poems by Arthur Rimbaud

1854 - 1891

Arthur Rimbaud Biography

Arthur Rimbaud, the enigmatic French poet, remains one of literature’s most captivating figures, embodying both youthful genius and the mythic allure of the rebel. Born on October 20, 1854, in Charleville, a small town in northeastern France, Rimbaud’s life was marked by a meteoric rise in the literary world, producing some of the most visionary and revolutionary poetry in the French canon before abandoning his craft at the age of twenty-one. His life was as intense and vivid as his poetry, and his works, though written in a brief period, have exerted a lasting influence on literature, inspiring the Surrealists, the Beats, and countless others drawn to his fervent exploration of consciousness and his disavowal of convention.

Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud was born to Marie Catherine Vitalie Cuif and Captain Frédéric Rimbaud, an army officer who was frequently absent from family life. His father’s departure from the household when Arthur was just six years old left the Rimbaud children to be raised under the strict, pious, and controlling guidance of their mother. Madame Rimbaud was a rigid woman who demanded moral uprightness and academic excellence from her children, instilling a discipline that would later clash with Rimbaud’s own burgeoning rebellious spirit. The constricted world of Charleville, coupled with his mother’s severity, created in young Arthur a profound longing for escape and adventure, themes that would later dominate his poetry.

An exceptionally gifted child, Rimbaud excelled academically, demonstrating an astonishing facility with language and literature from an early age. His teachers were frequently stunned by his intelligence, and he won multiple prizes in school competitions. But Rimbaud’s precociousness came with a disdain for authority; he developed a contempt for both academic institutions and his provincial surroundings. In these early years, he immersed himself in the works of the Romantic poets, especially Victor Hugo, who he famously idolized as “a Shakespeare of France.” Even as a schoolboy, Rimbaud’s writings reflected his profound dissatisfaction with bourgeois society, foreshadowing the radical impulses that would later characterize his poetry.

At fifteen, Rimbaud began writing poetry of remarkable maturity, grappling with themes of rebellion, disillusionment, and an intense desire to break free from social norms. In 1870, the Franco-Prussian War disrupted his studies, further fueling his desire to escape the confines of his small-town life. The war marked a turning point in French society, leading to the brief and radical Paris Commune, and igniting in Rimbaud a fascination with revolutionary ideals. He ran away to Paris several times, traveling without money and living as a vagabond. During these excursions, Rimbaud cultivated the image of a wild, unkempt poet—a role that became central to his mystique. By the time he was sixteen, he had not only written some of his most significant poems but had also fashioned himself as a defiant figure, rebelling against social expectations with a boldness unusual for his age.

Rimbaud’s work is characterized by a visionary intensity and an ambition to transcend traditional forms of poetic expression. His early poems often reveal a complex relationship with the Romanticism that preceded him. While he was drawn to the Romantic ideals of beauty, nature, and introspection, Rimbaud also rejected Romanticism’s emphasis on individual sentimentality, instead embracing a mode of expression that sought to dissolve the boundaries between the self and the world. In “The Drunken Boat” (“Le Bateau ivre”), one of his most famous poems, he imagines himself as a liberated vessel adrift on a sea of images, sensations, and metaphysical revelations. The poem is both an exploration of the ecstatic and terrifying dissolution of the self and a critique of the constraints of ordinary experience. Here, he uses hallucinatory imagery and a fluid, associative structure that would later be associated with Surrealism. The poem conveys both a profound sense of yearning for transcendence and an acknowledgment of the existential risks involved in the pursuit of visionary experiences.

Perhaps the most transformative relationship in Rimbaud’s life was his tumultuous and ultimately destructive affair with Paul Verlaine, a poet of the Parnassian school. In September 1871, Rimbaud sent Verlaine several of his poems, including “The Drunken Boat,” in an effort to gain the attention of established literary circles. Verlaine, deeply impressed by Rimbaud’s precocious genius, invited him to Paris, and the two began an intense relationship marked by mutual fascination and violent conflict. Verlaine, then twenty-seven and already married, became both mentor and lover to Rimbaud, introducing him to the Parisian avant-garde and immersing him in a bohemian lifestyle of absinthe and debauchery. Their relationship was scandalous and notorious, and it came to embody a fusion of artistic collaboration and destructive passion. Verlaine famously described Rimbaud as “an angel with a terrible face,” a phrase that captured the paradox of his beauty and cruelty, his innocence and danger.

Together, Rimbaud and Verlaine embarked on a journey through Belgium and England, living in a haze of alcohol and antagonism. The relationship reached a breaking point in July 1873, when Verlaine, in a drunken rage, shot Rimbaud in the wrist, leading to his arrest and imprisonment. Following the shooting incident, Rimbaud returned to his family home in Charleville to recover. During this period, he wrote A Season in Hell (Une Saison en Enfer), a work that reads like both a spiritual confession and a manifesto. The text is a hybrid of prose and poetry, chronicling Rimbaud’s journey through despair, ecstasy, and eventual disillusionment. In it, he reflects on his relationship with Verlaine, his disillusionment with life, and his attempts to understand his own psyche and artistic identity. The work’s confessional tone and fragmented structure echo the turmoil of his personal experiences, marking it as one of the most innovative literary texts of the nineteenth century.

Rimbaud’s subsequent work, Illuminations, further departs from traditional poetic forms and continues his exploration of visionary experience. Comprising a series of prose poems, Illuminations delves into surreal, dreamlike landscapes where images merge and dissolve in a kaleidoscope of colors, sounds, and sensations. The language in Illuminations is dense, symbolic, and at times opaque, resembling the associative logic of dreams. In poems like “Cities” and “Childhood,” he envisions worlds that are both fantastical and nightmarish, populated by surreal figures and landscapes that seem to elude fixed interpretation. This work not only prefigures Surrealism but also aligns with Symbolism, a movement that embraced ambiguity and the ineffable aspects of human experience.

Rimbaud’s departure from poetry is as mysterious as his arrival. In 1875, after a final meeting with Verlaine, he abandoned writing altogether, despite having established himself as a central figure in French literature. He embarked on a series of travels across Europe, the Middle East, and eventually Africa, where he worked as a trader, explorer, and arms dealer. His life in Africa marked a complete departure from his earlier identity as a poet; he became deeply involved in commerce and even learned Arabic, seemingly erasing all traces of his former literary life. This radical shift puzzled those who had known him as a poet, and for decades, his whereabouts remained unknown to the French literary establishment. For Rimbaud, it was as though his youthful literary career had been an aberration, a chapter in his life that he consciously closed.

The reasons for Rimbaud’s abandonment of poetry remain speculative, though it seems he saw his writing as a form of self-immolation, a path that led him through revelation and despair but ultimately proved unsustainable. In A Season in Hell, he alludes to his desire to renounce “the delusion of martyrdom,” suggesting that he viewed his poetic career as a form of personal sacrifice that could not continue indefinitely. His poetry had been an attempt to “derange the senses” and to achieve a kind of transcendence, but the intensity of this pursuit may have left him exhausted, unable or unwilling to continue living on the brink of spiritual and psychological annihilation.

Rimbaud returned to France in 1891, suffering from a debilitating illness that led to the amputation of his leg. He spent his final months in Marseille, cared for by his sister, and died on November 10, 1891, at the age of thirty-seven. Though his life was brief, Rimbaud’s influence on literature is immeasurable. His rejection of conventional forms, his embrace of experimental language, and his unrelenting pursuit of the “unknown” transformed him into a symbol of artistic rebellion. The Surrealists, especially André Breton, saw in Rimbaud a precursor to their own quest for the unconscious and the irrational. The Beats, including Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, found in Rimbaud’s life and work a model of the outsider, the visionary, and the iconoclast.

Rimbaud’s legacy lies not only in his extraordinary poetry but also in the myth of the artist he embodied—a myth that continues to captivate those who seek to transcend the boundaries of ordinary experience. His quest for the absolute, his audacity to push the limits of poetic language, and his refusal to conform have made him a lasting symbol of youthful genius and artistic defiance. To read Rimbaud is to encounter a mind in constant revolt, a poet who sought to “change life” through the alchemy of words, only to abandon his art when it could no longer satisfy his restless spirit. His work remains a testament to the power of poetry to evoke the sublime, the terrifying, and the unknown—a legacy that has secured his place among the immortals of literature.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Username Information

No username is open

Everything is free to use, but donations are always appreciated.

Quick Links

© 2024-2025 R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody).

All music on this site by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Attribution Requirement:

When using this music, you must give appropriate credit by including the following statement (or equivalent) wherever the music is used or credited:

"Music by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) – https://v2melody.com"

Support My Work:

If you enjoy this music and would like to support future creations, your thanks are always welcome but never required.

Thanks!