The Sleeper in the Valley (French)

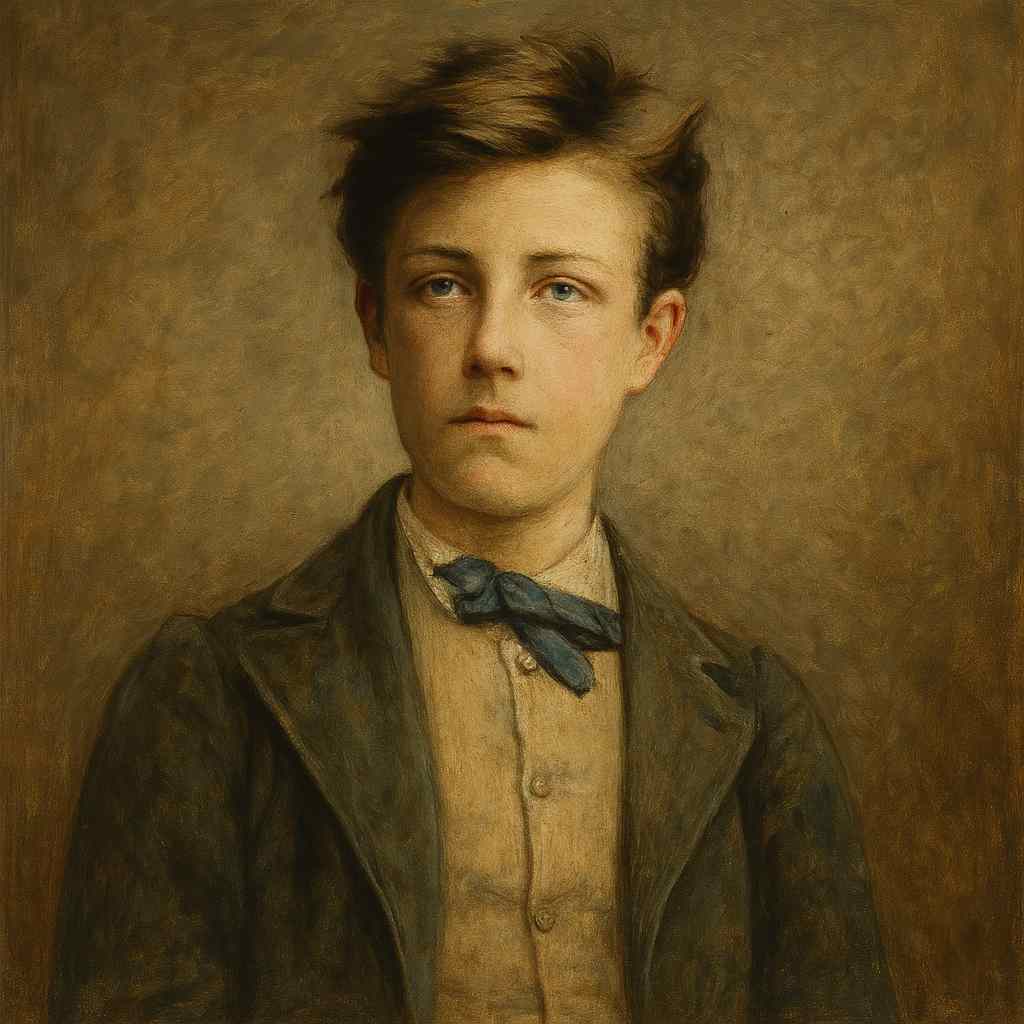

Arthur Rimbaud

1854 to 1891

Le Dormeur du Val

C'est un trou de verdure où chante une rivière,

Accrochant follement aux herbes des haillons

D'argent ; où le soleil, de la montagne fière,

Luit : c'est un petit val qui mousse de rayons.

Un soldat jeune, bouche ouverte, tête nue,

Et la nuque baignant dans le frais cresson bleu,

Dort ; il est étendu dans l'herbe, sous la nue,

Pâle dans son lit vert où la lumière pleut.

Les pieds dans les glaïeuls, il dort. Souriant comme

Sourirait un enfant malade, il fait un somme :

Nature, berce-le chaudement : il a froid.

Les parfums ne font pas frissonner sa narine ;

Il dort dans le soleil, la main sur sa poitrine,

Tranquille. Il a deux trous rouges au côté droit.

Arthur Rimbaud's The Sleeper in the Valley

Arthur Rimbaud’s The Sleeper in the Valley (Le Dormeur du Val) presents a serene and deceptively peaceful image of a soldier lying in a sunlit valley. Written in 1870, amidst the Franco-Prussian War, this poem captures both the innocence and horror of war, merging pastoral beauty with the tragic inevitability of death. Rimbaud’s technique—juxtaposing idyllic natural imagery with the shocking reality of a soldier's death—offers a profound anti-war message, conveyed through gentle irony and subtle yet impactful detail.

Form and Structure

This sonnet follows a 14-line structure typical of the form, organized into two quatrains and two tercets with a regular rhyme scheme (ABAB in the quatrains and CDD EEF in the tercets). Rimbaud’s use of the sonnet, traditionally associated with love and beauty, amplifies the irony, as the form's structure supports a pastoral theme that ultimately reveals the violence of war. The sonnet’s cadence, with enjambments that encourage fluid reading, lulls the reader into a tranquil mood before confronting them with the stark reality of the soldier’s death.

Imagery and Symbolism

The opening lines describe a valley alive with natural beauty: “It is a green hollow where a river sings, / Madly clinging to the grasses in rags / Of silver.” Here, Rimbaud introduces the setting as one filled with light and life, where the river “sings” and sunlight plays off the grasses. The "rags of silver" imagery, while beautiful, subtly foreshadows decay or something out of place within the pastoral scene. The sun, "from the proud mountain," illuminates this "little valley foaming with light," an image that emphasizes vibrancy and the dynamic force of nature.

In the second quatrain, the reader is introduced to the young soldier, who “sleeps” in a pose of quiet repose, his “mouth open, head bare, / And the nape of his neck bathing in cool blue cress.” This portrait of restfulness reinforces the idea of innocence. The color palette—cool blues and greens, the “pale” tone of his skin—intensifies the scene's serenity, while also implying the soldier’s vulnerability. The valley itself appears as a protective cradle for the soldier, yet this sense of shelter and peace is undermined by Rimbaud’s gradual hints that something is amiss.

The Ironic Tone and Subversion of Peaceful Imagery

Rimbaud skillfully leads readers to interpret the scene as one of rest rather than death, using language that connotes peace. The line “He sleeps” repeats several times, reinforcing the idea of slumber, which is gently subverted by descriptions such as “Pale in his green bed.” The soldier's smile, “like a sick child would smile,” suggests innocence but also unease. His expression, peaceful yet faintly troubled, hints at the tragedy lying beneath the surface.

The plea to Nature in the third stanza—“Nature, cradle him warmly: he is cold”—adds a further layer of irony. The tenderness of this line is laced with bitterness, as Nature cannot warm him; he is beyond its care. This invocation reveals Nature’s indifference to human suffering and death, highlighting the futility of war and the disconnect between humanity and the natural world.

The Devastating Revelation

The poem’s final line delivers its heartbreaking revelation: “He has two red holes in his right side.” This image of the bullet wounds shatters the previous illusion of sleep, confirming that the young soldier is dead. The shock lies not only in the revelation but in the gentle manner in which it is delivered, almost as an afterthought. Rimbaud masterfully withholds this detail until the last possible moment, allowing the reader to fully experience the beauty of the scene and the soldier's serene appearance before confronting the stark reality of his violent death. The peaceful tableau is thus violently disrupted, leaving the reader to grapple with the horror of war intruding upon nature’s tranquility.

Themes

The Sleeper in the Valley explores themes of innocence, nature, and the tragic costs of war. The soldier, depicted as a childlike figure, symbolizes the youth sacrificed in warfare. His "sleep" evokes both innocence and death, portraying war as an unnatural and tragic interruption of life. Nature’s beauty, contrasted with human brutality, emphasizes the senselessness of war; the valley, while calm and nurturing, becomes the unfeeling witness to human destruction. Rimbaud suggests that war disrupts the natural order, turning a place of peace into one of loss.

The poem’s subtle anti-war sentiment arises from its contrast between the soldier's innocence and the violence done to him. Rather than depict explicit battlefield horrors, Rimbaud relies on understatement and irony to underscore the tragedy, allowing readers to arrive at their own conclusions about the senselessness of war.

Conclusion

Arthur Rimbaud’s The Sleeper in the Valley is a poignant critique of war wrapped in the guise of pastoral imagery. Through his serene, almost reverent depiction of a young soldier’s body lying in a sunlit valley, Rimbaud captures both the beauty of life and the tragedy of its untimely end. The contrast between the valley’s peaceful setting and the soldier’s quiet death serves as a haunting reminder of the human cost of conflict. In this brief yet powerful sonnet, Rimbaud challenges readers to consider the violence of war not through scenes of battle, but through the silent, dignified image of a young life cut short in nature’s embrace.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!