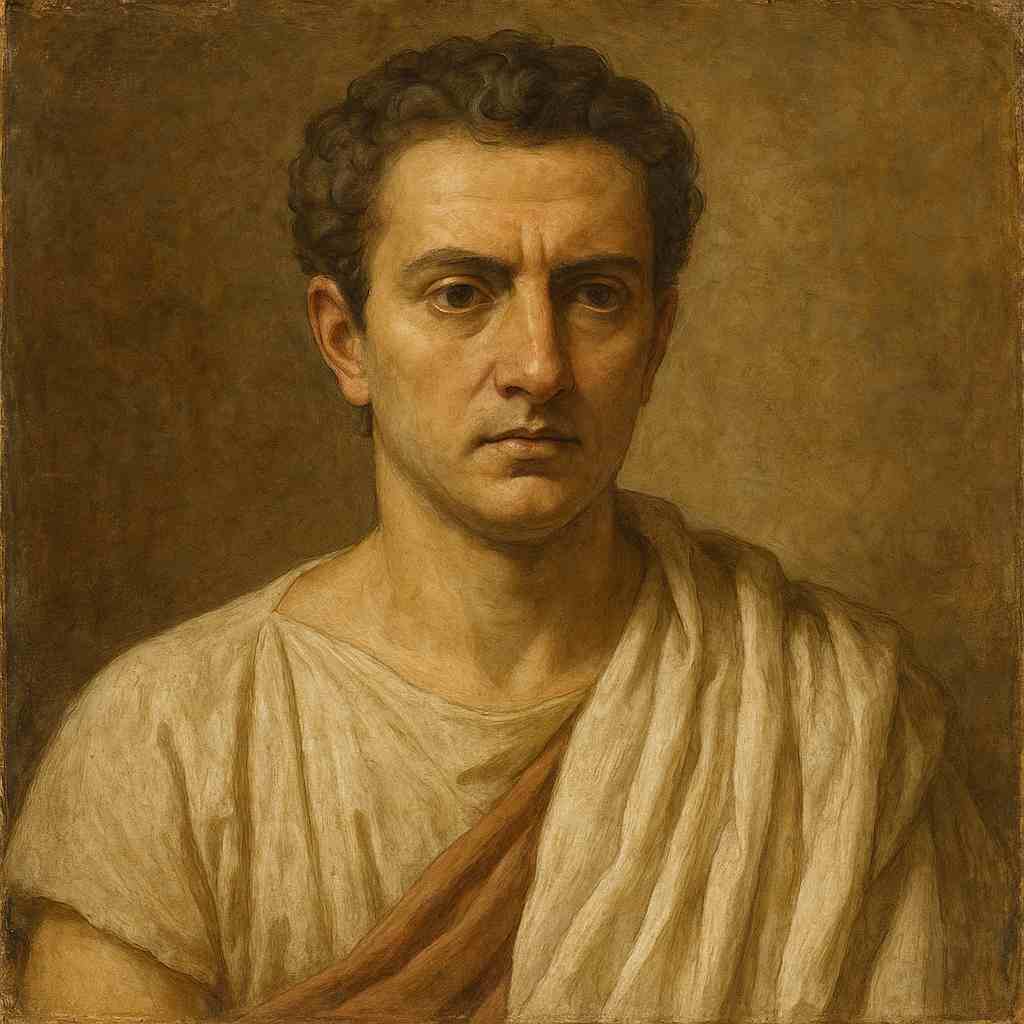

2 Poems by Gaius Valerius Catullus

84 BCE - 54 BCE

Gaius Valerius Catullus Biography

Gaius Valerius Catullus, born around 84 BCE in Verona, stands out in Roman poetry not only for his stylistic innovation but also for his deeply personal, often volatile reflections on love, friendship, and enmity. In an age where poetry served as a public tribute to Roman ideals and political figures, Catullus dared to bring his most intimate emotions to the forefront, establishing himself as a rare poetic voice that transcended the conventions of his time. Though much of his life remains shrouded in mystery, the emotional intensity and personal quality of his work have allowed readers across centuries to connect with him, creating a vivid portrait of a man immersed in passionate love, bitter betrayal, and unrestrained wit. His works, though relatively few in number, demonstrate a mastery of language and form, revealing his ability to evoke the thrill of romance, the sting of insult, and the melancholy of loss with unmatched fervor and immediacy.

Catullus was born into a wealthy equestrian family in Verona, a Roman colony in northern Italy. This provincial origin set him apart from the cosmopolitan circles of Rome, where he would later seek recognition and distinction. His family was well-connected—historical accounts suggest that Julius Caesar himself was acquainted with Catullus’s father, hinting at a background of influence and privilege. However, the poet's verses reveal a mind far more interested in the subtleties of personal experience than in the grandeur of statecraft. His move to Rome as a young man likely marked the beginning of his involvement with the neoteric poets, a group that sought to redefine the nature of Roman literature by drawing inspiration from the refined, intricate works of Hellenistic poets like Callimachus. These "new poets" emphasized polish, wit, and brevity, often turning away from the lengthy epics of their predecessors to explore themes of love, beauty, and art.

Among the many relationships that Catullus chronicled in his poetry, none is more famous or more complex than his romance with "Lesbia." This pseudonym, likely chosen in homage to the poet Sappho from the island of Lesbos, conceals the identity of the woman who dominates much of his verse and his emotional life. Scholars generally agree that Lesbia was Clodia, a notorious aristocrat known for her intelligence, beauty, and libertine lifestyle. Clodia was married, and her relationships, as well as her political influence, were the subject of public fascination and scorn. The affair between Catullus and Lesbia was thus highly scandalous, but it also served as the raw material for some of his most arresting poetry. Through the Lesbia poems, Catullus reveals a deeply conflicted man whose love oscillates between adoration and resentment, devotion and disdain. His lines range from the blissful sensuality of their early romance to a profound sense of betrayal and self-loathing as their relationship disintegrates. This progression is most famously captured in his declaration of odi et amo—I hate and I love—a paradox that epitomizes the tension between passion and reason, a central theme in his work.

Catullus’s poems about Lesbia, such as Poem 5 (“Let us live, my Lesbia, and let us love”) or Poem 51 (an adaptation of Sappho’s famous ode on the sensations of love), reveal his remarkable command of tone and nuance. In Poem 5, he implores Lesbia to ignore the judgments of “the old men” and embrace their love in the moment, counting the kisses they will share as if love could transcend mortality through sheer intensity. But this bright optimism is undercut by other poems in which he feels abandoned or deceived, transforming the very language of love into a weapon of reproach. In these verses, Catullus seems to question his own susceptibility to passion and its power to unmoor him from rationality and self-respect. His heartbreak over Lesbia resonates not only as a personal agony but as a universal experience, depicted with such sincerity and poignancy that it feels timeless.

Beyond his tumultuous love life, Catullus’s poetry engages with broader social and political themes, although often through a highly personal lens. His friendships, for instance, are frequently lauded, and his circle of companions, such as Calvus, Varus, and Cinna, feature prominently in his work. Yet, even these friendships are not immune to his sharp wit and criticism. When his friends disappoint or betray him, Catullus does not hesitate to express his anger. For example, in Poem 30, he upbraids his friend Alfenus for abandoning him in a time of need, combining his disappointment with sarcasm and wit. In another instance, his famous invective against Gellius, a probable rival in love, highlights the fierceness of his emotions when confronted with betrayal. This personal animosity spills over into public satire as well, with Catullus directing scathing verses at prominent figures of his day, including Julius Caesar and Cicero. His attack on Mamurra, a corrupt officer close to Caesar, and his scornful address to Caesar himself demonstrate that even those at the highest echelons of power were not beyond the reach of his lampoons. Remarkably, while Catullus’s poems could be brutal in their contempt, Caesar reportedly forgave the poet, recognizing the young man’s talent and perhaps acknowledging the literary tradition that allowed for poetic dissent.

Catullus’s thematic breadth is matched by his technical mastery, encompassing various forms and meters. His collection, the Carmina, includes short lyric poems, epigrams, elegies, and even mini-epics. Some of his longer poems reveal his debt to Hellenistic aesthetics, displaying a meticulous attention to structure and form. In Poem 64, his retelling of the myth of Peleus and Thetis, Catullus crafts an epic-style narrative that explores themes of love, fate, and human folly. Here, he showcases his erudition and his ability to weave mythological allusions into a narrative that feels both grand and intimate. The digression within this poem, which details the tragic love story of Ariadne and Theseus, serves as a mirror for his own experiences with love’s volatility. This juxtaposition between the mythic and the personal highlights Catullus’s insight into the timeless patterns of human emotion, and his willingness to interrogate them with a rare mix of empathy and irony.

Catullus’s unique voice was further distinguished by his innovations in Latin diction and the colloquial boldness of his language. While many Roman poets adhered to a formal and elevated vocabulary, Catullus freely incorporated the vernacular, lending his poetry an immediacy that other writers often lacked. His use of diminutives, for instance, endows his verses with a playful, almost teasing tone, which he employs to charming and sardonic effect. In his invective poems, his language becomes vividly obscene, a feature that aligns him with the tradition of Greek iambic poetry but stands in stark contrast to the decorum expected in Roman literature. Such vulgarity was daring, even revolutionary, for its time, as Catullus openly flouted the strictures of Roman respectability. His willingness to challenge conventions of taste was matched by his disregard for traditional moral judgments, as he seemed intent on presenting his emotions with unvarnished honesty, whether they be expressions of love, lust, anger, or grief.

Though Catullus's literary career was brief—he is thought to have died around 54 BCE, possibly before reaching the age of thirty—his influence on later Roman poets was profound. Horace, Propertius, and Ovid all drew inspiration from his candid treatment of personal themes and his embrace of the Greek-influenced aesthetics of the neoteric movement. Even Virgil, whose Aeneid embodies the epic grandeur that Catullus often rejected, shows traces of Catullus’s influence in his lyricism and in his sensitivity to the emotional lives of his characters. The deeply personal nature of Catullus’s poetry, along with his stylistic inventiveness, paved the way for the Roman love elegy, a genre that would reach its zenith in the works of Propertius, Tibullus, and Ovid. By centering the self in his poetry, Catullus laid the foundation for a literary tradition that prioritized introspection and personal expression, allowing for an intimacy in poetry that Roman literature had rarely seen before.

Despite his enduring impact on Latin poetry, Catullus’s work was nearly lost to history. After the fall of Rome, his poems fell into obscurity, and it was not until the Renaissance that they were rediscovered and recognized for their brilliance. Since then, Catullus has fascinated scholars and poets alike, from the humanists of the 16th century to modernists in the 20th century. His unfiltered examination of human desire and vulnerability has resonated across ages, offering a poetic model that blends emotional intensity with linguistic precision. Modern readers, in particular, find in Catullus an almost contemporary sensibility, as he captures the contradictions and passions of human relationships in a manner that feels astonishingly relevant. His work, with its alternating tenderness and scorn, invites readers into the turbulent psyche of a poet whose love and anger alike reveal an unflinching engagement with life’s complexities.

In Catullus, we find a poet who, though writing in a time of strict social codes and political tension, refused to censor his emotions or conform to literary expectations. His poetry reminds us that love can be as fierce as it is fragile, that satire can serve as both a shield and a weapon, and that the personal can indeed be the most profound. Through his work, Catullus grants us a glimpse into the timeless struggles of the heart and mind, exploring the boundaries of desire and the sting of betrayal with a clarity that remains unmatched.

His legacy endures not only in the canon of Latin literature but in the broader tradition of poetry that seeks to capture the full spectrum of human experience. In his life and his lines, Catullus challenges us to confront our own passions and prejudices, inviting us to share in the highs and lows of a man who dared to make his heart the subject of his art.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Username Information

No username is open

Everything is free to use, but donations are always appreciated.

Quick Links

© 2024-2025 R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody).

All music on this site by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Attribution Requirement:

When using this music, you must give appropriate credit by including the following statement (or equivalent) wherever the music is used or credited:

"Music by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) – https://v2melody.com"

Support My Work:

If you enjoy this music and would like to support future creations, your thanks are always welcome but never required.

Thanks!