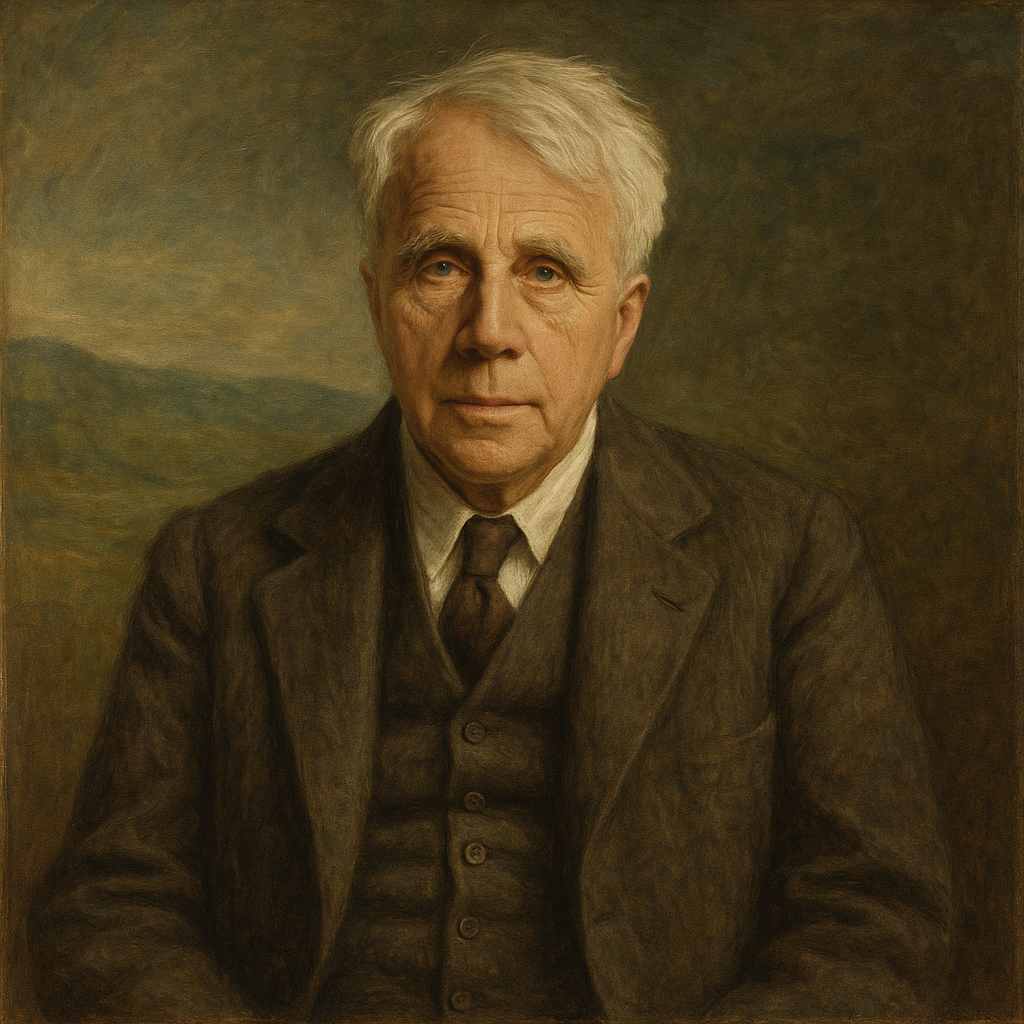

5 Poems by Robert Frost

1874 - 1963

Robert Frost Biography

Robert Frost, born on March 26, 1874, in San Francisco, California, is widely regarded as one of the most significant and popular American poets of the 20th century. His work, known for its realistic depictions of rural life and its profound philosophical undertones, has become an integral part of the American literary canon.

Frost's early life was marked by loss and upheaval. His father, William Prescott Frost Jr., died of tuberculosis when Robert was only eleven, leaving the family in difficult financial circumstances. Following his father's death, Frost moved with his mother and sister to Lawrence, Massachusetts, his paternal grandfather's home. This move from the urban West Coast to rural New England would profoundly influence Frost's poetry, providing the backdrop for many of his most famous works.

Frost's formal education began at Lawrence High School, where he excelled academically and first began to write poetry. He briefly attended Dartmouth College in 1892 but left after a few months. In 1894, he sold his first poem, "My Butterfly: An Elegy," to The Independent, a New York literary journal. This early success encouraged him to pursue a career in poetry.

In 1895, Frost married Elinor White, his high school co-valedictorian and longtime sweetheart. Their marriage, which lasted until Elinor's death in 1938, was complex and sometimes troubled, marked by personal tragedies including the loss of four of their six children. These experiences of loss and hardship would deeply inform Frost's poetry, contributing to the undercurrent of darkness that often runs beneath the surface of his seemingly simple verses.

Despite his early publication, Frost struggled to establish himself as a poet in the United States. In 1912, at the age of 38, he moved his family to England, hoping to find a more receptive audience for his work. This move proved pivotal for his career. In England, he found a community of fellow poets, including Ezra Pound, who helped promote his work. Frost's first two books of poetry, "A Boy's Will" (1913) and "North of Boston" (1914), were published in England to critical acclaim.

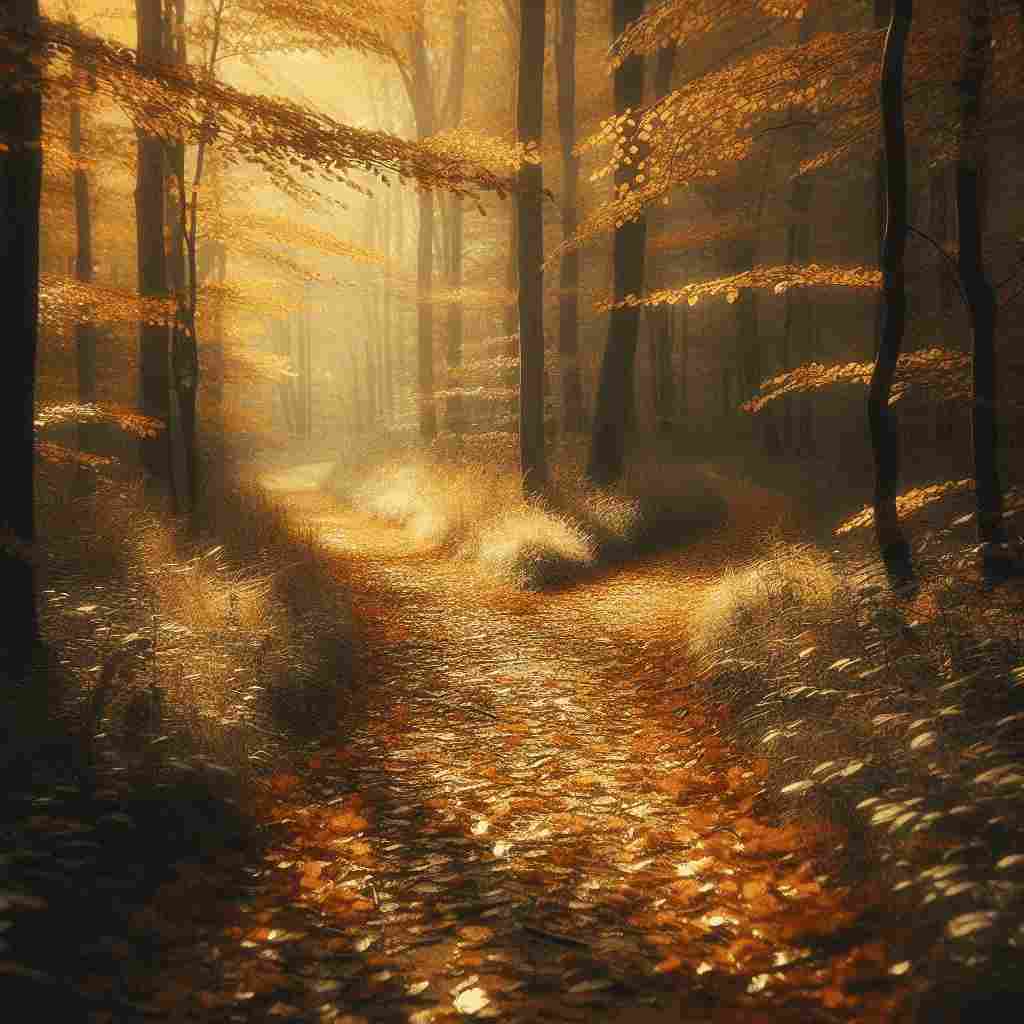

Frost returned to the United States in 1915, buoyed by his success abroad and the growing interest in his work at home. He settled on a farm in Franconia, New Hampshire, which would serve as his home for the next five years and inspire much of his poetry. During this period, he produced some of his most famous works, including "The Road Not Taken," "Mending Wall," and "Birches."

Frost's poetry is characterized by its accessibility, its use of colloquial language, and its exploration of complex philosophical themes through simple, often rural, imagery. He frequently employed traditional forms and meters, particularly blank verse and the sonnet, but did so with a conversational tone that made his work feel both familiar and profound.

One of Frost's most distinctive features as a poet is his use of the dramatic monologue and dialogue. Poems like "Mending Wall" and "The Death of the Hired Man" showcase his ability to capture the rhythms and nuances of New England speech, while also exploring deeper themes of human interaction and isolation.

Nature plays a central role in much of Frost's poetry, but rarely in a simple or idealized way. Instead, he often uses natural settings and phenomena as metaphors for human experiences and emotions. In "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening," for example, the snowy woods become a symbol for the temptation of death or oblivion, while the speaker's choice to continue on his journey represents the pull of social obligations and the human will to live.

Frost's poetry often grapples with the tension between individual desires and societal expectations, between the beauty of nature and its indifference to human concerns. This complexity is evident in poems like "The Road Not Taken," which is often misinterpreted as a straightforward celebration of individualism, but actually contains a more nuanced reflection on the way we construct narratives about our choices.

As Frost's reputation grew, he became increasingly involved in academic life. He held teaching positions at Amherst College, the University of Michigan, and Harvard University, among others. These roles allowed him to influence a new generation of poets and to refine his own poetic theories, which he expounded in essays and lectures.

Frost's later years were marked by both public acclaim and personal tragedy. He received numerous honors, including four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry (in 1924, 1931, 1937, and 1943), and was increasingly recognized as a national cultural figure. In 1961, at the age of 86, he recited his poem "The Gift Outright" at President John F. Kennedy's inauguration, cementing his status as America's unofficial poet laureate.

However, these years also saw the deaths of his wife, two daughters, and a son, experiences that deepened the vein of sorrow in his later work. Poems from this period, such as "Directive" and "Acquainted with the Night," reflect a growing preoccupation with themes of loss, isolation, and the search for meaning in a seemingly indifferent universe.

Frost died on January 29, 1963, in Boston, leaving behind a body of work that continues to be widely read and studied. His influence on American poetry has been profound and lasting. He helped to establish a distinctly American poetic voice, one that combined traditional forms with the rhythms of everyday speech and the imagery of ordinary life.

In the realm of literary criticism, Frost's work has been subject to varied interpretations over the years. While initially praised primarily for its depictions of rural New England life, later critics have focused on the psychological depth and philosophical complexity of his poetry. His use of ambiguity and understatement has been particularly noted, with many scholars arguing that the apparent simplicity of his poems often masks deeper, more troubling insights.

Robert Frost's legacy extends far beyond the world of poetry. His verses have become part of the American cultural lexicon, quoted in political speeches, inscribed on monuments, and taught in classrooms across the country. His ability to blend accessible language with profound insight, to find universal truths in the particulars of rural New England life, has ensured his place as one of the most beloved and enduring poets in the English language.

Frost once defined poetry as "a way of taking life by the throat." This vivid metaphor encapsulates much of what makes his work so powerful and enduring. Through his poetry, Frost grappled with the fundamental questions of human existence – love, death, the nature of choice, the relationship between humans and the natural world – in a way that was both deeply personal and universally resonant. His work continues to challenge, console, and inspire readers, affirming his place as a central figure in American literature and culture.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Username Information

No username is open

Everything is free to use, but donations are always appreciated.

Quick Links

© 2024-2025 R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody).

All music on this site by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Attribution Requirement:

When using this music, you must give appropriate credit by including the following statement (or equivalent) wherever the music is used or credited:

"Music by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) – https://v2melody.com"

Support My Work:

If you enjoy this music and would like to support future creations, your thanks are always welcome but never required.

Thanks!