Nothing Gold Can Stay

Robert Frost

1874 to 1963

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

Nature's first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold,

Her early leaf's a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

Robert Frost's Nothing Gold Can Stay

Robert Frost's poem "Nothing Gold Can Stay" stands as a masterpiece of concision and depth, encapsulating profound philosophical insights within its mere eight lines. This brief yet potent work, published in 1923 as part of Frost's Pulitzer Prize-winning collection "New Hampshire," exemplifies the poet's ability to distill complex observations about nature, time, and human experience into deceptively simple verses. Through a meticulous examination of its formal elements, imagery, and thematic resonances, we can uncover the layers of meaning embedded in this compact lyric and appreciate its enduring significance in American poetry.

Formal Structure and Sonic Artistry

The poem's formal structure is integral to its impact and meaning. Composed of four rhyming couplets (AABBCCDD), the poem's tight construction mirrors its thematic focus on brevity and transience. The consistent meter—each line containing exactly six syllables—creates a rhythmic regularity that paradoxically underscores the poem's central theme of impermanence. This tension between form and content is characteristic of Frost's work, demonstrating his mastery of traditional poetic techniques in service of modern sensibilities.

The sonic qualities of "Nothing Gold Can Stay" are equally significant. Frost employs a combination of alliteration, assonance, and consonance to create a musical texture that enhances the poem's emotional resonance. The repetition of 'g' sounds in "gold," "green," and "grief" links these key concepts sonically, while the assonance in "hour" and "flower" reinforces their conceptual connection. The hard consonants in "hardest" and "hold" evoke a sense of struggle against inevitable change, contrasting with the softer sounds in "subsides" and "sank," which suggest surrender to natural processes.

Imagery and Symbolism

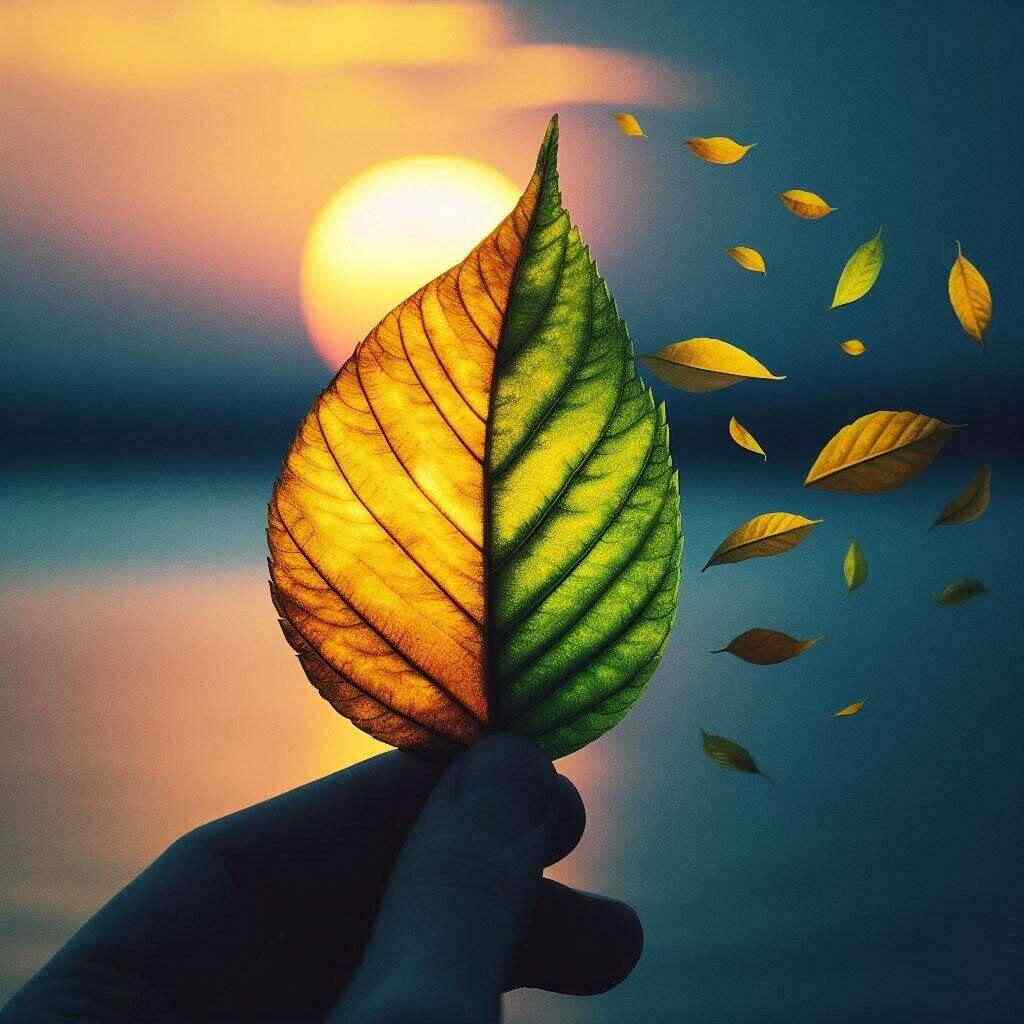

Frost's imagery in "Nothing Gold Can Stay" is both vivid and multifaceted. The poem opens with a paradoxical statement: "Nature's first green is gold." This line immediately establishes the central motif of transformation and introduces the color symbolism that runs throughout the poem. Gold, traditionally associated with value, permanence, and divinity, is here linked to the fleeting beauty of early spring. The "green" of new growth is metaphorically transmuted into "gold," suggesting both its preciousness and its ephemeral nature.

The progression of images in the poem traces the lifecycle of a leaf, from its earliest emergence to its eventual fall. This microcosm of natural change serves as a powerful metaphor for broader cycles of existence. The description of the early leaf as a "flower" evokes the delicate beauty of new life, while also hinting at its fragility. The transition from "flower" to "leaf" represents maturation, but also a loss of initial splendor.

Frost's reference to Eden in the sixth line broadens the poem's scope, connecting the natural imagery to biblical and mythological concepts. The allusion to humanity's fall from grace adds a layer of spiritual and existential meaning to the poem's reflections on change and loss. This juxtaposition of the quotidian (a leaf changing color) with the cosmic (the loss of paradise) is characteristic of Frost's ability to find profound significance in everyday observations.

Thematic Complexity

At its core, "Nothing Gold Can Stay" is a meditation on the transience of beauty, youth, and life itself. However, the poem's thematic richness extends far beyond this initial observation. Frost explores the tension between desire and reality, the human struggle against time, and the bittersweet nature of existence.

The repetition of "So" at the beginning of lines 6 and 7 creates a sense of inevitability, linking the fall of Eden, the passage of dawn into day, and by extension, all processes of change and decline. This fatalistic tone is tempered, however, by the poem's appreciation for the beauty that exists precisely because of its impermanence. The golden hue of early spring leaves is "hardest... to hold" not despite but because of its fleeting nature.

Moreover, the poem invites consideration of the cyclical nature of existence. While the focus is primarily on decline and loss, the imagery of dawn and spring suggests the possibility of renewal. This ambiguity is characteristic of Frost's nuanced worldview, which recognizes both the tragedy and the necessity of change.

Literary and Philosophical Contexts

"Nothing Gold Can Stay" can be productively situated within multiple literary and philosophical traditions. Its concern with mutability and the passage of time echoes themes found in Shakespeare's sonnets and the metaphysical poetry of John Donne. The poem's use of natural imagery to explore existential questions aligns it with the American Transcendentalist tradition, particularly the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

Philosophically, the poem engages with concepts central to existentialism and phenomenology. Its focus on the lived experience of time and change resonates with Martin Heidegger's explorations of temporality and being-in-the-world. The tension between the desire for permanence and the reality of flux recalls ancient Greek philosophy, particularly Heraclitus's famous assertion that one cannot step into the same river twice.

Frost's Poetic Vision

"Nothing Gold Can Stay" exemplifies several key aspects of Frost's poetic vision. His ability to find universal truths in particular observations of nature is on full display here. The poem also demonstrates Frost's characteristic blend of traditional form and modern sensibility, using familiar rhyme schemes and metrical patterns to convey complex, often ambiguous ideas.

Furthermore, the poem showcases Frost's talent for compressing expansive concepts into concise, memorable phrases. The title itself, repeated as the poem's final line, has entered the cultural lexicon as a shorthand for the brevity of youth and beauty. This capacity for creating aphoristic statements that resonate beyond their immediate context is a hallmark of Frost's enduring popularity and influence.

Conclusion

Robert Frost's "Nothing Gold Can Stay" stands as a testament to the power of poetry to encapsulate profound truths in minimal space. Through its deft use of formal elements, evocative imagery, and thematic depth, the poem offers a meditation on the nature of existence that continues to resonate with readers a century after its composition. Its exploration of beauty, transience, and the human experience of time invites multiple readings and interpretations, ensuring its place in the canon of American literature.

As we engage with this compact masterpiece, we are reminded of poetry's unique capacity to crystallize complex emotions and ideas into language that is at once accessible and profound. "Nothing Gold Can Stay" not only exemplifies Frost's mastery of his craft but also serves as a touchstone for understanding the human condition in all its fleeting glory and inevitable decline. In its brief span, the poem achieves what all great art aspires to: it makes us see the familiar world anew, with heightened awareness of both its beauty and its impermanence.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more