Here lie the beasts

Dylan Thomas

1914 to 1953

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

Here lie the beasts of man and here I feast,

The dead man said,

And silently I milk the devil’s breast.

Here spring the silent venoms of his blood,

Here clings the meat to sever from his side.

Hell’s in the dust.

Here lies the beast of man and here his angels,

The dead man said,

And silently I milk the buried flowers.

Here drips a silent honey in my shroud,

Here slips the ghost who made of my pale bed

The heaven’s house.

Dylan Thomas's Here lie the beasts

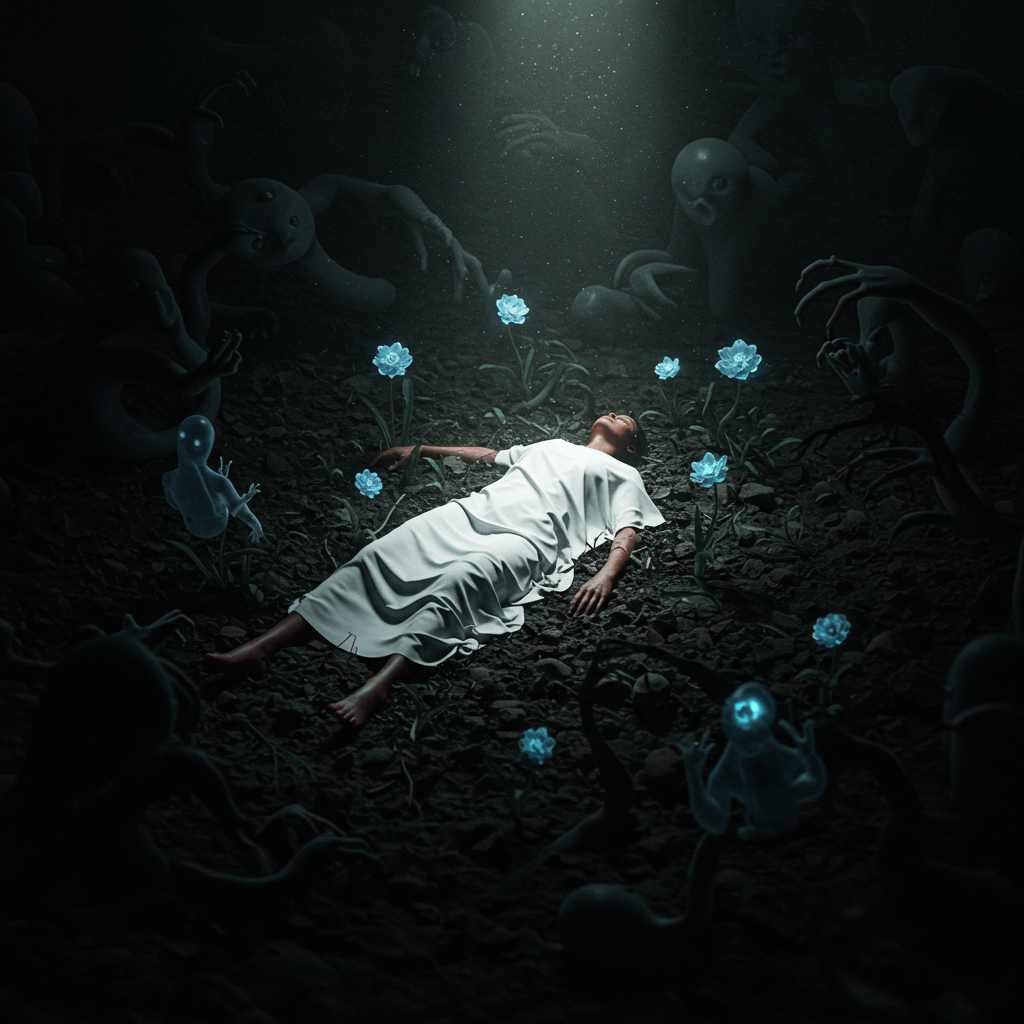

Dylan Thomas’s enigmatic poem Here Lie the Beasts is a haunting meditation on mortality, sin, and the paradoxical coexistence of the sacred and the profane. Written in Thomas’s characteristically dense, lyrical style, the poem explores themes of death, corruption, and transcendence through vivid, often grotesque imagery. Its historical and cultural context—rooted in mid-20th-century existential anxieties—alongside its rich literary devices and emotional intensity, make it a compelling subject for analysis. This essay will examine the poem’s historical backdrop, its use of metaphor and symbolism, its thematic concerns, and its visceral emotional impact. Additionally, we will consider Thomas’s broader body of work and philosophical influences to illuminate the poem’s deeper resonances.

Historical and Cultural Context

Dylan Thomas (1914–1953) wrote during a period of profound upheaval—World War II and its aftermath cast long shadows over literature, fostering existential dread and a preoccupation with mortality. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Thomas was not overtly political; instead, his work grappled with universal human fears and desires, often through a lens of mysticism and bodily decay. Here Lie the Beasts reflects this sensibility, blending religious imagery with visceral, almost surreal depictions of death.

The mid-20th century also saw the rise of psychoanalytic thought, which may inform Thomas’s fascination with the subconscious and the duality of human nature. The poem’s juxtaposition of "beasts" and "angels" suggests a Freudian tension between base instincts and spiritual aspirations. Furthermore, Thomas’s Welsh heritage, steeped in bardic tradition and Christian symbolism, infuses the poem with a mythic quality, as if the speaker is both a corpse and a prophet.

Literary Devices and Symbolism

Thomas’s poetry is renowned for its dense, musical language, and Here Lie the Beasts is no exception. The poem employs a range of literary devices to evoke its unsettling vision of death and transcendence.

1. Paradox and Juxtaposition

The poem thrives on contradictions, merging the sacred and the grotesque. The opening line—"Here lie the beasts of man and here I feast"—immediately establishes a paradox: the dead man is both a decaying body and an active participant in his own dissolution. The act of feasting, typically associated with vitality, becomes macabre when performed by a corpse. Similarly, the line "silently I milk the devil’s breast" conflates nurturing imagery with diabolic connotations, suggesting that even in death, the speaker is sustained by sin or corruption.

2. Religious and Mythic Symbolism

Thomas frequently drew upon Christian and pagan imagery, and this poem is rife with allusions to both. The "devil’s breast" evokes the succubus or Lilith, figures of temptation, while "buried flowers" and "silent honey" suggest a corrupted Eden. The final lines—"The heaven’s house"—transform the grave into a site of ascension, implying that death is not an end but a transmutation. This duality reflects Thomas’s ambivalent relationship with religion: though he rejected orthodox faith, his work is suffused with spiritual longing.

3. Sensory Imagery

The poem’s power lies in its tactile, almost visceral descriptions. Phrases like "Here clings the meat to sever from his side" and "Here drips a silent honey in my shroud" engage multiple senses—touch, taste, even smell—to create a disquieting intimacy with decay. The "silent honey" is particularly striking, as it suggests something sweet yet cloying, perhaps the lingering remnants of life or memory.

4. Repetition and Refrain

The repetition of "The dead man said" functions like a chant or incantation, reinforcing the speaker’s liminal state between life and death. The refrain also lends the poem a ritualistic quality, as if the dead man is reciting his own epitaph.

Themes

1. The Duality of Human Nature

The central tension in the poem is between the "beasts of man" and his "angels"—the primal and the divine. Thomas suggests that these forces are not separate but intertwined; even in death, the speaker is both corrupted and exalted. This aligns with Thomas’s broader preoccupation with the body as a site of both decay and transcendence, as seen in poems like And death shall have no dominion.

2. Death as Transformation

Rather than portraying death as mere annihilation, the poem presents it as an alchemical process. The speaker "milks the buried flowers," extracting sustenance from decay, and his "pale bed" becomes "the heaven’s house." This echoes mystical traditions (such as alchemy or Kabbalah) where death is a necessary stage in spiritual rebirth.

3. Sin and Redemption

The imagery of the "devil’s breast" and "silent venoms" suggests that the speaker is complicit in his own corruption. Yet, there is also a suggestion of redemption—the "ghost" who transforms the grave into heaven implies that even in sin, there is the potential for transcendence. This ambiguity reflects Thomas’s complex relationship with morality, where beauty and horror coexist.

Emotional Impact

The poem’s emotional force lies in its unsettling beauty. The juxtaposition of decay and delicacy—rotting meat alongside dripping honey—creates a paradoxical sense of awe and revulsion. The speaker’s voice, both resigned and eerily serene, invites the reader to contemplate their own mortality without despair. There is a quiet triumph in the final lines, as if the grave is not an end but a threshold.

Comparative and Philosophical Perspectives

Thomas’s work often invites comparison with other poets who grapple with death and transcendence. The metaphysical preoccupations of John Donne (particularly Death Be Not Proud) come to mind, as does the grotesque beauty of Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal. Philosophically, the poem resonates with existentialist thought—the idea that meaning is not given but forged through confrontation with mortality.

Conclusion

Here Lie the Beasts is a masterful exploration of death’s duality, blending visceral decay with spiritual elevation. Through its rich symbolism, paradoxes, and sensory imagery, the poem captures the unsettling yet transcendent nature of mortality. Situated within Thomas’s oeuvre and mid-20th-century existential anxieties, it remains a powerful meditation on the beasts and angels within us all. Its emotional resonance lingers, like the "silent honey" in the shroud, long after the final line.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more