Mutton

Gertrude Stein

1874 to 1946

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

A letter which can wither, a learning which can suffer and an outrage which is simultaneous is principal.

Student, students are merciful and recognised they chew something.

Hate rests that is solid and sparse and all in a shape and largely very largely. Interleaved and successive and a sample of smell all this makes a certainty a shade.

Light curls very light curls have no more curliness than soup. This is not a subject.

Change a single stream of denting and change it hurriedly, what does it express, it expresses nausea. Like a very strange likeness and pink, like that and not more like that than the same resemblance and not more like that than no middle space in cutting.

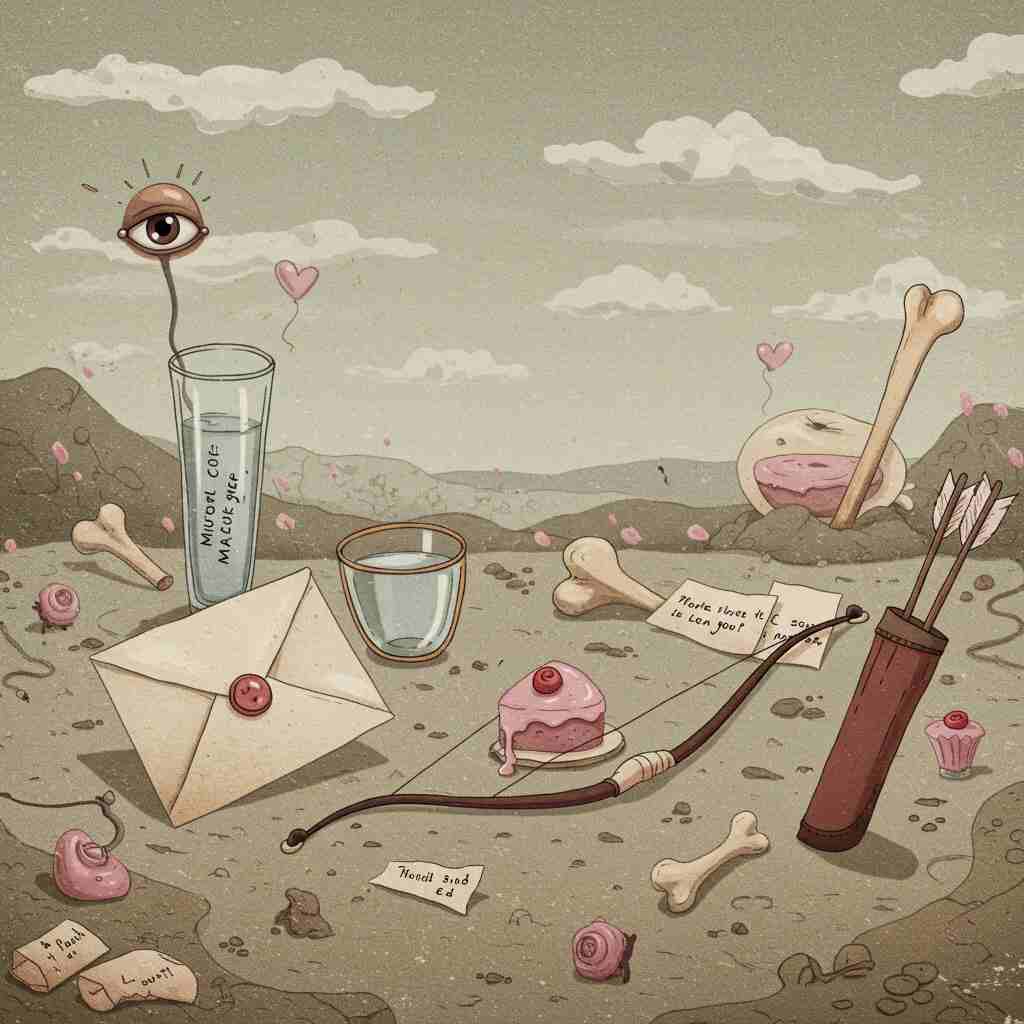

An eye glass, what is an eye glass, it is water. A splendid specimen, what is it when it is little and tender so that there are parts. A centre can place and four are no more and two and two are not middle.

Melting and not minding, safety and powder, a particular recollection and a sincere solitude all this makes a shunning so thorough and so unrepeated and surely if there is anything left it is a bone. It is not solitary.

Any space is not quiet it is so likely to be shiny. Darkness very dark darkness is sectional. There is a way to see in onion and surely very surely rhubarb and a tomato, surely very surely there is that seeding. A little thing in is a little thing.

Mud and water were not present and not any more of either. Silk and stockings were not present and not any more of either. A receptacle and a symbol and no monster were present and no more. This made a piece show and was it a kindness, it can be asked was it a kindness to have it warmer, was it a kindness and does gliding mean more. Does it.

Does it dirty a ceiling. It does not. Is it dainty, it is if prices are sweet. Is it lamentable, it is not if there is no undertaker. Is it curious, it is not when there is youth. All this makes a line, it even makes makes no more. All this makes cherries. The reason that there is a suggestion in vanity is due to this that there is a burst of mixed music.

A temptation any temptation is an exclamation if there are misdeeds and little bones. It is not astonishing that bones mingle as they vary not at all and in any case why is a bone outstanding, it is so because the circumstance that does not make a cake and character is so easily churned and cherished.

Mouse and mountain and a quiver, a quaint statue and pain in an exterior and silence more silence louder shows salmon a mischief intender. A cake, a real salve made of mutton and liquor, a specially retained rinsing and an established cork and blazing, this which resignation influences and restrains, restrains more altogether. A sign is the specimen spoken.

A meal in mutton, mutton, why is lamb cheaper, it is cheaper because so little is more. Lecture, lecture and repeat instruction.

Gertrude Stein's Mutton

Gertrude Stein’s Mutton, a subpoem within her avant-garde collection Tender Buttons (1914), defies conventional poetic logic to interrogate language, perception, and societal structures through a prism of radical fragmentation. Written during the zenith of modernist experimentation, the poem exemplifies Stein’s cubist-inspired dismantling of linguistic norms, weaving domesticity, mythology, and psychological introspection into a tapestry of disorienting yet resonant imagery. Below is a detailed analysis of its historical context, literary devices, and thematic undercurrents, anchored in scholarly perspectives and biographical insights.

Historical and Cultural Context: Modernism’s Culinary Revolt

Stein composed Tender Buttons amid early 20th-century upheavals in art and thought. Her association with Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, whom she championed as a patron3, informed her cubist approach to language-breaking objects into fractured, multidimensional perspectives. In Mutton, this manifests in the deconstruction of food as both a domestic staple and a socio-economic signifier. The line “a meal in mutton, mutton, why is lamb cheaper, it is cheaper because so little is more”2 transforms a culinary query into a critique of value systems, juxtaposing economic pragmatism (“little is more”) with the visceral act of consumption.

The poem’s focus on food aligns with Stein’s subversion of traditionally feminine domestic spaces. While Tender Buttons categorizes its subjects as “Objects,” “Food,” and “Rooms,” Stein destabilizes these groupings through paradoxical associations. For instance, “a splendid specimen, what is it when it is little and tender so that there are parts” conflates anatomical dissection with culinary preparation, reflecting her abandoned medical career4. This interplay between dissection and nourishment mirrors modernist anxieties about fragmentation and wholeness, themes also explored in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922). Unlike Eliot’s reliance on historical allusions, however, Stein’s “collage of ideas”2 rejects hierarchical structures, privileging immediacy over tradition.

Literary Devices: Cubist Syntax and Sonic Play

Stein’s prose-poetic form rejects linear narrative, instead employing repetition, paradox, and sonic texture to evoke sensory and intellectual dissonance:

-

Repetition and Fragmentation:

The insistent recurrence of “mutton” and “lecture” (“Lecture, lecture and repeat instruction”) mimics both the mechanical act of chewing2 and the futility of didactic communication. Words become objects to be “slowly chewed over”2, their meanings destabilized through iterative force. -

Sonic Materiality:

The poem’s acoustics-such as the “lip-buzzing m” and “tongue-tipping n” in “mutton”6-invoke the physicality of eating. Lines like “Light curls very light curls have no more curliness than soup” merge visual and tactile imagery, transforming language into a synesthetic experience. -

Paradox and Nonsense:

Stein’s deliberate contradictions (“darkness very dark darkness is sectional”) frustrate logical parsing, mirroring the disorientation of modern consciousness. The question “Is it lamentable, it is not if there is no undertaker” absurdly ties emotional gravity to practicality, undermining societal expectations of propriety.

Themes: Identity, Perception, and the Unsayable

-

The Instability of Language:

Stein treats words as mutable entities, divorced from fixed referents. The stanza “An eye glass, what is an eye glass, it is water” reductively redefines objects, challenging readers to question linguistic certainty. This aligns with her belief that “words as things in themselves”8 could transcend symbolic limitations, a concept paralleling Picasso’s cubist rejection of representational art3. -

Domesticity and Power Dynamics:

The poem’s focus on food-mutton, cherries, cake-subverts traditional gender roles. The “burst of mixed music” accompanying cherries alludes to George Washington’s mythologized honesty, yet Stein undercuts this patriotism by framing it within a domestic “line” of inquiry1. Similarly, “a real salve made of mutton and liquor” merges remedy and indulgence, complicating binaries of care and excess. -

Existential Solitude:

Recurring motifs of bones (“surely if there is anything left it is a bone”) and “sincere solitude” evoke emotional austerity. Critics link this imagery to Stein’s personal struggles, including her failed medical career and turbulent romantic relationships14. The “bone” symbolizes residual truths stripped of societal pretense-a stark counterpoint to the “melting” fluidity of language.

Emotional Impact: Disorientation and Intimacy

The poem’s fragmented syntax elicits a visceral response, oscillating between alienation and revelation. Lines like “Change a single stream of denting and change it hurriedly, what does it express, it expresses nausea” evoke modernist angst, yet Stein tempers this with whimsy (“All this makes cherries”). This duality mirrors her psychological studies under William James, whose theories on stream-of-consciousness influenced her exploration of “divided attention”5. The reader’s struggle to reconcile disparate images-“Mouse and mountain and a quiver, a quaint statue and pain in an exterior”-parallels the existential tension between coherence and chaos.

Comparative and Philosophical Perspectives

Stein’s work resonates with contemporary modernist experiments but diverges in its rejection of narrative rescue. Unlike Eliot’s The Waste Land, which seeks redemption through cultural synthesis, Mutton embraces ambiguity as its own truth. The poem’s focus on “surfaces” over depth2 aligns with Husserlian phenomenology, privileging immediate perception over abstract reconstruction. Furthermore, Stein’s queer identity inflects her subversion of domestic tropes; the line “custard is better than seeding”2 has been interpreted as a coded celebration of non-procreative love, challenging heteronormative paradigms.

Conclusion

Mutton exemplifies Stein’s radical reimagining of poetry as a site of linguistic and existential ferment. By destabilizing syntax, interrogating domesticity, and confronting the limits of communication, she crafts a work that is as intellectually provocative as it is emotionally resonant. The poem’s enduring power lies in its refusal to offer solace-instead, it invites readers to revel in the chaos of meaning-making, much like the modernist era itself. As Stein once wrote, “A rose is a rose is a rose,” yet in Mutton, even the rose is subject to decomposition and rebirth.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more