Why is a pale white not paler than blue

Gertrude Stein

1874 to 1946

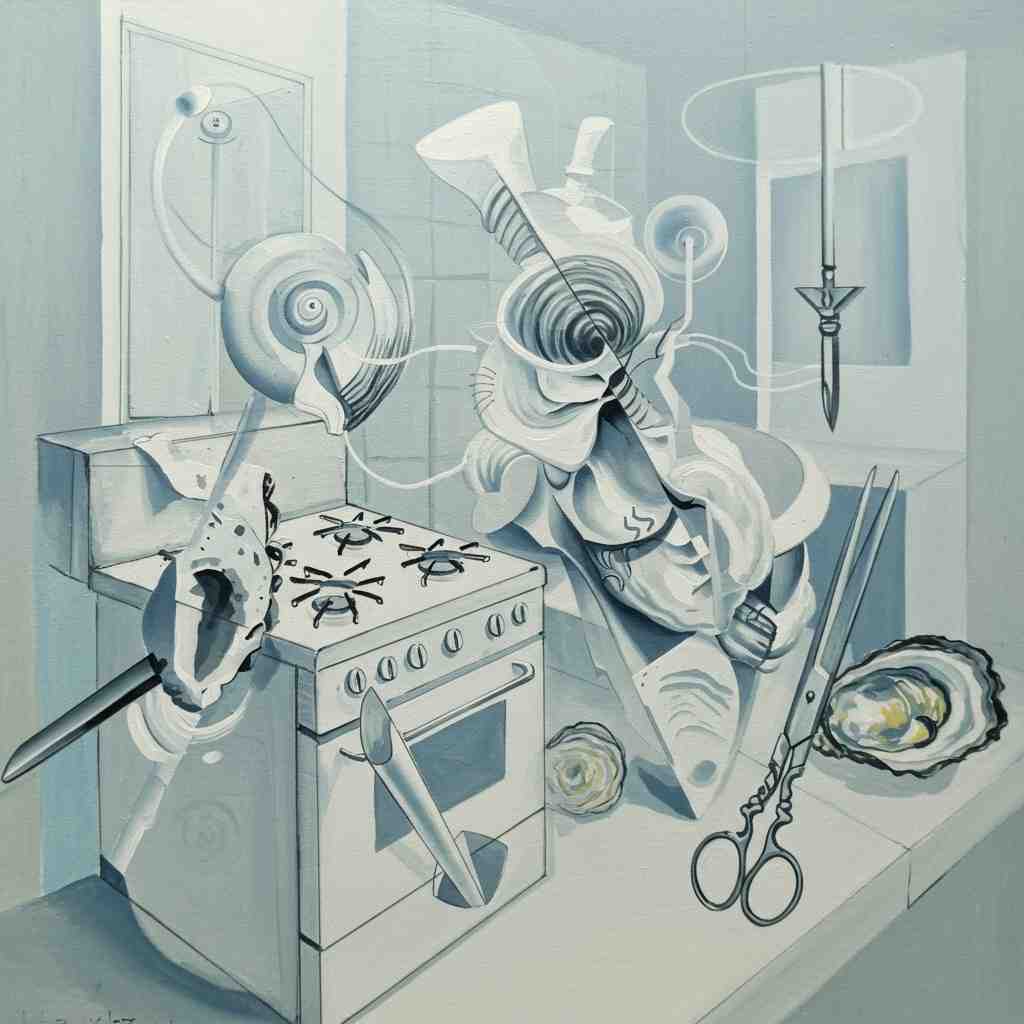

Why is a pale white not paler than blue, why is a connection made by a stove, why is the example which is mentioned not shown to be the same, why is there no adjustment between the place and the separate attention. Why is there a choice in gamboling. Why is there no necessary dull stable, why is there a single piece of any color, why is there that sensible silence. Why is there the resistance in a mixture, why is there no poster, why is there that in the window, why is there no suggester, why is there no window, why is there no oyster closer. Why is there a circular diminisher, why is there a bather, why is there no scraper, why is there a dinner, why is there a bell ringer, why is there a duster, why is there a section of a similar resemblance, why is there that scissor.

Gertrude Stein's Why is a pale white not paler than blue

Gertrude Stein’s Why is a pale white not paler than blue is a quintessential example of her avant-garde poetic style, one that challenges conventional linguistic structures, semantic coherence, and the very foundations of meaning-making in poetry. Written during the height of modernism, Stein’s work resists traditional interpretation, instead inviting readers into a labyrinth of repetition, abstraction, and syntactic play. This analysis will explore the poem through multiple lenses—linguistic deconstruction, historical and biographical context, philosophical implications, and emotional resonance—to uncover the ways in which Stein disrupts and redefines poetic expression.

The Disruption of Language and Meaning

At its core, Stein’s poem is an exercise in linguistic experimentation. The relentless repetition of the interrogative "why is" creates a rhythmic insistence, yet the questions themselves defy logical resolution. Each line presents a seemingly arbitrary juxtaposition of images and concepts: "a pale white not paler than blue," "a connection made by a stove," "a circular diminisher." These phrases resist straightforward interpretation, instead functioning as linguistic objects that demand active engagement from the reader.

Stein’s approach aligns with her broader artistic philosophy, influenced by her interest in Cubism—a movement that sought to fragment and reassemble visual perspectives. Just as Picasso and Braque broke objects into geometric planes, Stein dismantles language, forcing readers to confront words not as transparent vessels of meaning but as material entities with their own textures and resistances. The line "why is there that sensible silence" exemplifies this: silence, typically an absence, is rendered "sensible," thus made palpable, almost tactile. Stein’s language does not describe; it enacts perception.

Historical and Biographical Context

Stein wrote during a period of radical artistic upheaval. The early 20th century saw the rise of modernism, a movement characterized by its break from tradition, its embrace of fragmentation, and its fascination with the subconscious. Stein, an expatriate in Paris, was at the center of this revolution, surrounded by artists like Picasso, Matisse, and writers such as Hemingway and Fitzgerald. Her work, however, was even more radical in its rejection of narrative and symbolic conventions.

Biographically, Stein’s fascination with repetition and linguistic play can be traced to her academic background in psychology under William James, whose theories on stream of consciousness and habitual thought influenced her. The repetitive, almost incantatory quality of Why is a pale white not paler than blue suggests a meditation on the nature of questioning itself—less about finding answers than about the process of inquiry.

Philosophical Underpinnings: Stein and Wittgenstein

An illuminating parallel can be drawn between Stein’s poetic method and Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophical investigations into language. Wittgenstein’s later work, particularly Philosophical Investigations, argues that meaning is derived from use rather than fixed definitions. Stein’s poem operates similarly: the meaning of "why is there no oyster closer" is not found in a dictionary but in the way the phrase interacts with the surrounding lines, creating a network of associations rather than a linear argument.

Furthermore, the poem’s relentless questioning mirrors existential and phenomenological inquiries. The lack of resolution in each line—"why is there no adjustment between the place and the separate attention"—reflects the human tendency to seek patterns and connections even in the face of ambiguity. Stein’s refusal to provide answers becomes, paradoxically, an answer in itself: language, like perception, is unstable, and meaning is perpetually deferred.

Themes of Perception and Reality

One of the central themes in the poem is the instability of perception. The opening line—"why is a pale white not paler than blue"—immediately destabilizes color as a fixed category. Colors are relational, contingent on context, and Stein’s phrasing suggests that even descriptive language is inadequate to capture perceptual experience. This aligns with her broader project of defamiliarization, forcing readers to see (or hear) language anew.

Similarly, the references to everyday objects—"a stove," "a window," "a dinner"—are stripped of their utilitarian meanings. A stove does not cook; it makes "a connection." A window is not for looking through but is questioned for its very existence: "why is there no window." Stein’s world is one where objects are liberated from function, existing purely as linguistic constructs.

Emotional Resonance: Playfulness and Disorientation

Despite its abstract nature, the poem elicits a distinct emotional response. The repetitive questioning creates a childlike curiosity, yet the lack of resolution produces a sense of unease. The reader is caught between amusement and frustration, a tension that mirrors the modernist preoccupation with the breakdown of coherent reality.

There is also a musicality to Stein’s phrasing—the assonance in "circular diminisher," the abruptness of "why is there that scissor"—that engages the ear even when the mind struggles for meaning. This sonic quality suggests that the poem is as much about the experience of hearing language as it is about deciphering it.

Comparative Readings: Stein and the Surrealists

Stein’s work shares affinities with Surrealist automatic writing, which sought to bypass rational thought to access deeper subconscious truths. However, while Surrealists like Breton embraced dream logic, Stein’s repetitions feel more deliberate, more concerned with the materiality of language itself. A comparison with Dadaist poetry, particularly Hugo Ball’s sound poems, further highlights Stein’s unique position: where Dada sought to dismantle meaning entirely, Stein reconstructs it in abstract, non-referential forms.

Conclusion: The Enduring Challenge of Stein’s Poetry

Why is a pale white not paler than blue remains a provocative work precisely because it refuses to conform to interpretive demands. It is a poem that must be experienced rather than decoded, a meditation on the limits of language and the fluidity of perception. In resisting closure, Stein invites readers to participate in the creation of meaning, making each encounter with the poem a unique act of collaboration between text and mind.

Ultimately, Stein’s genius lies in her ability to make language strange, to remind us that words are not just tools but living, shifting entities. Her poem does not provide answers—it asks us to reconsider the very nature of questioning. In doing so, it captures the essence of modernist experimentation: a bold, relentless reimagining of what art can be.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem analysis. This exercise is designed for classroom use.