Mary, Pity Women!

Rudyard Kipling

1865 to 1936

You call yourself a man,

For all you used to swear,

An' leave me, as you can,

My certain shame to bear?

I 'ear! You do not care—

You done the worst you know.

I 'ate you, grinnin' there....

Ah, Gawd, I love you so!

Nice while it lasted, an' now it is over—

Tear out your 'eart an' good-bye to your lover!

What's the use o' grievin', when the mother that bore you

(Mary, pity women!) knew it all before you?

It aren't no false alarm,

The finish to your fun;

You—you 'ave brung the 'arm,

An' I'm the ruined one;

An' now you'll off an' run

With some new fool in tow.

Your 'eart? You 'aven't none....

Ah, Gawd, I love you so!

When a man is tired there is naught will bind 'im;

All 'e solemn promised 'e will shove be'ind 'im.

What's the good o' prayin' for The Wrath to strike 'im

(Mary, pity women!), when the rest are like 'im?

What 'ope for me or—it?

What's left for us to do?

I've walked with men a bit,

But this—but this is you.

So 'elp me Christ, it's true!

Where can I 'ide or go?

You coward through and through!...

Ah, Gawd, I love you so!

All the more you give 'em the less are they for givin'—

Love lies dead, an' you cannot kiss 'im livin'.

Down the road 'e led you there is no returnin'

(Mary, pity women!), but you're late in learnin'!

You'd like to treat me fair?

You can't, because we're pore?

We'd starve? What do I care!

We might, but this is shore!

I want the name—no more—

The name, an' lines to show,

An' not to be an 'ore....

Ah, Gawd, I love you so!

What's the good o' pleadin', when the mother that bore you

(Mary, pity women!) knew it all before you?

Sleep on 'is promises an' wake to your sorrow

(Mary, pity women!), for we sail to-morrow!

Rudyard Kipling's Mary, Pity Women!

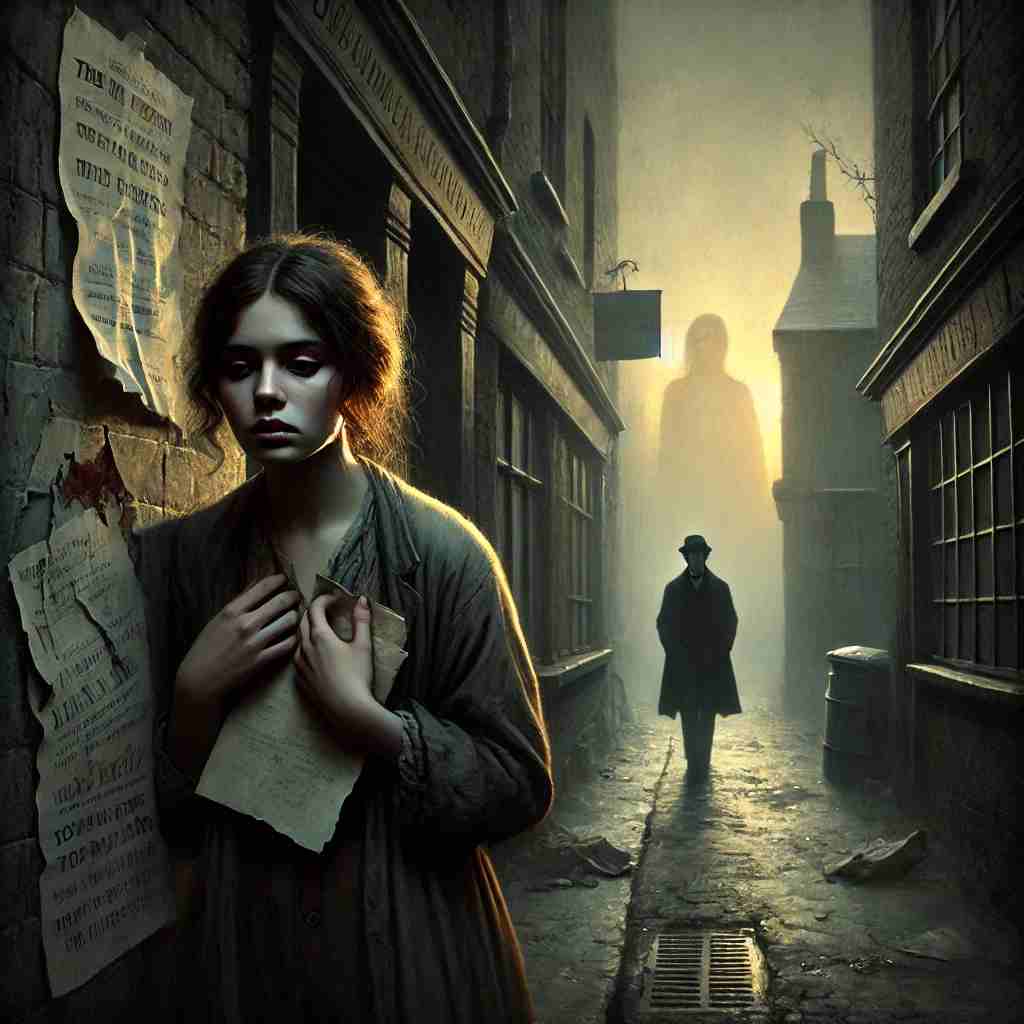

Rudyard Kipling’s "Mary, Pity Women!" is a poignant exploration of love, betrayal, and the gendered suffering of women in a patriarchal society. Written in Kipling’s signature vernacular style, the poem captures the raw emotional turmoil of a woman abandoned by her lover, oscillating between fury and desperate affection. Through its vivid imagery, biting irony, and invocation of divine pity, the poem critiques societal norms that leave women vulnerable to male exploitation. This essay will examine the poem’s historical and cultural context, its literary devices, central themes, and emotional impact, while also considering philosophical and comparative perspectives where relevant.

Historical and Cultural Context

Kipling wrote during the late Victorian and early Edwardian eras, a time when rigid gender roles dictated that women were morally and socially subordinate to men. The poem reflects the double standard in sexual morality: men could engage in premarital or extramarital affairs with relative impunity, while women faced ruin—social ostracism, economic destitution, and the loss of reputation—for the same behavior. The speaker’s lament, "An’ I’m the ruined one," underscores this disparity, highlighting the irreversible consequences women bore for male indiscretions.

The invocation of "Mary"—the Virgin Mary—situates the poem within a Christian framework that idealizes female purity while offering little practical solace to fallen women. The refrain "(Mary, pity women!)" functions as both a plea and an indictment, suggesting that divine compassion is the only recourse for women betrayed by men and abandoned by society.

Additionally, Kipling’s use of working-class dialect ("’ear," "’ate," "’ope") grounds the poem in a specific socio-economic reality. The speaker is not an aristocratic woman who might have some protection through family wealth or name; she is an ordinary woman whose ruin is absolute. This linguistic choice amplifies the poem’s emotional authenticity and social critique.

Literary Devices and Structure

1. Dramatic Monologue & Vernacular Speech

The poem adopts the form of a dramatic monologue, allowing the speaker’s voice to dominate with visceral immediacy. The colloquial diction and contractions ("’aven’t," "’ope," "’arm") lend authenticity to her anguish, making her fury and despair palpable. The abrupt shifts in tone—from condemnation ("You coward through and through!") to helpless adoration ("Ah, Gawd, I love you so!")—mirror the psychological turmoil of an abused lover who cannot extricate herself from emotional bondage.

2. Irony and Paradox

The central paradox of the poem lies in the speaker’s simultaneous hatred and love for her betrayer. The line "I 'ate you, grinnin' there.... / Ah, Gawd, I love you so!" encapsulates this contradiction, illustrating the tragic complexity of abusive relationships. The refrain "Mary, pity women!" is similarly ironic: it acknowledges that women’s suffering is so predictable that even the Virgin Mary, a symbol of maternal compassion, must have foreseen it.

3. Repetition and Refrain

The recurring line "(Mary, pity women!)" serves as a lamentation and a bitter commentary on the cyclical nature of female suffering. Each repetition reinforces the inevitability of betrayal, suggesting that women’s pain is a historical constant rather than an individual tragedy.

4. Imagery of Ruin and Abandonment

Kipling employs stark imagery to convey the speaker’s devastation:

-

"The finish to your fun; / You—you 'ave brung the 'arm, / An’ I’m the ruined one"—the man’s pleasure directly causes her destruction.

-

"Down the road 'e led you there is no returnin’"—a metaphor for irreversible ruin, suggesting that once a woman is "fallen," redemption is impossible in the eyes of society.

5. Allusion to Christian Theology

The references to Christ ("So 'elp me Christ, it’s true!") and the Virgin Mary frame the poem within a religious context that both condemns and consoles. The speaker’s cry for divine pity underscores the absence of earthly justice for women in her position.

Themes

1. The Cruelty of Male Betrayal

The poem exposes the callousness of a man who abandons his lover without remorse. Lines like "When a man is tired there is naught will bind 'im" and "All 'e solemn promised 'e will shove be'ind 'im" critique male fickleness and the ease with which men discard women once their desires are satisfied.

2. The Inescapability of Female Suffering

The refrain "knew it all before you" suggests that women’s pain is a foregone conclusion, passed down through generations. The speaker’s realization that "the rest are like 'im" implies systemic male treachery, leaving women with little hope for justice.

3. Love as Both Salvation and Torment

The speaker’s conflicted emotions—rage coexisting with helpless love—illustrate the psychological trap of abusive relationships. Her cry, "Ah, Gawd, I love you so!" is not romantic but tragic, revealing how societal conditioning keeps women emotionally bound to those who harm them.

4. Economic and Social Vulnerability

The lines "You can’t, because we’re pore? / We’d starve?" highlight the economic dimensions of female dependence. Without marriage, the speaker faces destitution, yet even the prospect of starvation does not outweigh her need for the "name—no more"—the respectability of marriage.

Emotional Impact and Philosophical Underpinnings

The poem’s emotional power lies in its unflinching portrayal of a woman’s despair. Unlike Victorian sentimental poetry, which often idealized female suffering, Kipling’s work is raw and accusatory. The speaker’s voice wavers between defiance and desolation, making her plight disturbingly relatable.

Philosophically, the poem aligns with Schopenhauer’s view of love as a cruel illusion that perpetuates suffering. The speaker’s love persists despite her betrayal, illustrating how emotion overrides reason, dooming her to misery.

Comparatively, the poem echoes Thomas Hardy’s "The Ruined Maid," which also critiques the sexual double standard. However, while Hardy employs irony to expose societal hypocrisy, Kipling’s approach is more visceral, immersing the reader in the speaker’s anguish.

Conclusion

"Mary, Pity Women!" is a masterful blend of social critique and emotional intensity. Through its vernacular diction, ironic refrains, and stark imagery, Kipling exposes the gendered injustices of his time while crafting a timeless lament for betrayed women. The poem’s enduring relevance lies in its unflinching depiction of love’s destructive power and the societal structures that perpetuate female suffering. In invoking Mary’s pity, Kipling does not offer salvation but rather underscores the tragic inevitability of women’s sorrow—a sorrow as old as history itself.

This poem remains a testament to Kipling’s ability to channel raw human emotion into verse, ensuring that the speaker’s cry—"Ah, Gawd, I love you so!"—resonates across generations as both a confession and a condemnation.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more