A Sleep Song

Nora Hopper Chesson

1871 to 1906

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

O Sleep, go. Sleep, hasten to my lover,

Leave my eyelids all forlorn of thy quiet breath;

Where my love lies wakeful, go thou and lean over,

Singing low, singing slow, dearest child of Death.

Fair Sleep, rare Sleep, Death that is thy father,

Night that is thy mother, both sow flowers for thee;

White poppies dashed with dew, drowsy flowers to gather,

Yellow rose that silence saith to the busiest bee.

Hear, Sleep, dear Sleep, ere my song be ended —

Gather me thy fairest flowers a soft dream to make

For my love — a dream of scent and of music blended.

Ay, and let me kiss the dream for the dreamer's sake.

O Sleep, blow sleep-dust upon his pillow

Till he dreams it is my breast, and to dream is fain;

Let him think it is my hair, not thy branch of willow,

Dark against the little light through the rain-blurred pane.

Nora Hopper Chesson's A Sleep Song

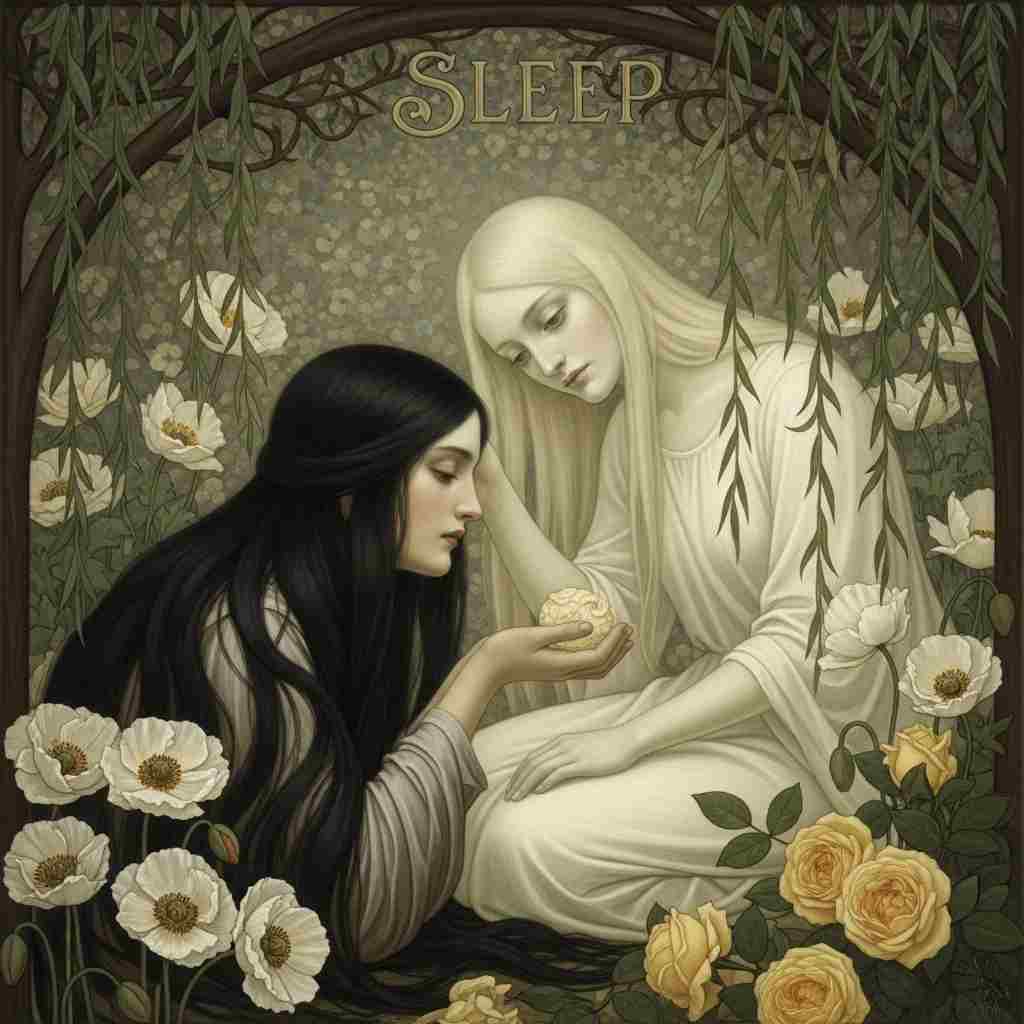

Nora Hopper Chesson’s A Sleep Song is a hauntingly beautiful lyric poem that explores the liminal space between wakefulness and slumber, love and loss, presence and absence. Through its invocation of Sleep as a personified force, the poem weaves together themes of longing, mortality, and the transcendent power of dreams. Chesson’s work is deeply rooted in the late-Victorian aesthetic, drawing from Celtic mythology, Decadent symbolism, and the broader fin-de-siècle fascination with the interplay between eros and thanatos. This essay will examine the poem’s historical and cultural context, its intricate literary devices, its thematic preoccupations, and its emotional resonance, while also considering its place within Chesson’s broader oeuvre and the literary movements of her time.

Historical and Cultural Context

Nora Hopper Chesson (1871–1906) was an Irish poet and novelist whose work was deeply influenced by the Celtic Revival and the Aesthetic movement. Writing in the 1890s and early 1900s, she was part of a generation of poets—including W.B. Yeats, Katharine Tynan, and Lionel Johnson—who sought to reclaim and reimagine Irish folklore within a modern poetic framework. A Sleep Song reflects this cultural moment, blending mythological imagery with a distinctly late-Victorian sensibility.

The poem’s preoccupation with Sleep as a mythological figure aligns with the Decadent and Symbolist movements, which often personified abstract concepts (such as Death, Love, and Sleep) to explore psychological and metaphysical states. The influence of French Symbolists like Paul Verlaine and Stéphane Mallarmé is evident in Chesson’s ethereal, dreamlike diction. Additionally, the poem’s focus on the liminal—the threshold between waking and dreaming—resonates with the Victorian fascination with the supernatural, as seen in the works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Christina Rossetti.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Chesson employs a rich tapestry of literary devices to create a hypnotic, incantatory effect. The poem’s most striking feature is its personification of Sleep, which is depicted as a divine intermediary between life and death. Sleep is described as the "dearest child of Death," suggesting an intimate connection between rest and mortality. This familial metaphor (with Night as mother and Death as father) evokes classical mythology, particularly figures like Hypnos (Sleep) and Thanatos (Death) from Greek lore.

The sensory imagery is lush and evocative, appealing to both sight and sound. Phrases like "white poppies dashed with dew" and "yellow rose that silence saith to the busiest bee" create a dreamscape that is at once delicate and intoxicating. The poppy, a traditional symbol of sleep and oblivion, reinforces the poem’s thematic concerns, while the "busiest bee" silenced by the rose suggests a cessation of worldly activity—a surrender to dream.

Another key device is the imperative voice, as the speaker repeatedly commands Sleep to act: "O Sleep, go," "Hear, Sleep," "O Sleep, blow sleep-dust." This creates a ritualistic quality, as if the poem itself were a spell or lullaby meant to conjure dreams. The urgency of these commands underscores the speaker’s desperation, reinforcing the emotional stakes of the poem.

Themes: Longing, Mortality, and the Power of Dreams

At its core, A Sleep Song is a poem about longing—specifically, the longing to bridge physical separation through dreams. The speaker implores Sleep to visit their absent lover, crafting a dream so vivid that it becomes a surrogate for physical presence:

"Let him think it is my hair, not thy branch of willow,

Dark against the little light through the rain-blurred pane."

Here, the "branch of willow" (a traditional symbol of mourning) is transformed into the lover’s hair, blurring the line between dream and reality. The "rain-blurred pane" further enhances this liminality, suggesting a world seen imperfectly, as if through tears or a veil.

The poem also grapples with mortality, framing Sleep as Death’s kin. This association is neither fearful nor morbid but rather tender, suggesting that sleep—and by extension, dreams—offer a temporary reprieve from the pain of separation. The speaker’s request to "kiss the dream for the dreamer’s sake" implies that dreams are not mere illusions but sacred, almost sacramental, experiences.

Comparative Analysis: Chesson and Her Contemporaries

Chesson’s work can be fruitfully compared to that of her contemporaries, particularly W.B. Yeats and Katharine Tynan. Like Yeats’s early poetry, A Sleep Song employs mythological motifs to explore emotional and spiritual longing. However, where Yeats often leans toward the political and nationalistic, Chesson’s focus remains intimate and personal.

Similarly, Katharine Tynan’s devotional and romantic lyrics share Chesson’s preoccupation with absence and desire. Yet Chesson’s imagery is more overtly sensual, aligning her with the Aesthetic movement’s celebration of beauty for its own sake. The line "Let him think it is my breast" carries an erotic charge that distinguishes her from more restrained Victorian poets.

Philosophical and Emotional Resonance

Philosophically, A Sleep Song engages with the nature of reality and illusion. The speaker does not dismiss dreams as mere fantasy but elevates them to a form of communion. This aligns with Arthur Schopenhauer’s notion that art and dreams provide temporary escape from the suffering of existence—a view that deeply influenced Decadent and Symbolist writers.

Emotionally, the poem is suffused with a quiet melancholy, a yearning that is both tender and sorrowful. The final image—of the lover mistaking a willow branch for the speaker’s hair—is achingly poignant, suggesting that even in dreams, presence is fragile and elusive.

Conclusion

Nora Hopper Chesson’s A Sleep Song is a masterful exploration of love, loss, and the liminal spaces between waking and dreaming. Through its rich symbolism, incantatory rhythm, and emotional depth, the poem transcends its late-Victorian context to speak to universal human experiences. It is a testament to Chesson’s skill as a poet that, over a century later, her words still resonate with such haunting beauty. For modern readers, the poem serves as a reminder of the power of dreams—not as escapes from reality, but as bridges across the distances that divide us.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more