Adlestrop

Edward Thomas

1878 to 1917

Yes. I remember Adlestrop —

The name, because one afternoon

Of heat the express-train drew up there

Unwontedly. It was late June.

The steam hissed. Some one cleared his throat.

No one left and no one came

On the bare platform. What I saw

Was Adlestrop — only the name

And willows, willow-herb, and grass,

And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry,

No whit less still and lonely fair

Than the high cloudlets in the sky.

And for that minute a blackbird sang

Close by, and around him, mistier,

Farther and farther, all the birds

Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.

Edward Thomas's Adlestrop

Introduction

Edward Thomas's "Adlestrop" stands as a quintessential example of early 20th-century English poetry, encapsulating the essence of rural England and the fleeting nature of memory. This deceptively simple sixteen-line poem, published posthumously in 1917, has become one of Thomas's most celebrated works, inviting readers into a moment of unexpected stillness amidst the rush of modern life. Through a close examination of its structure, imagery, and thematic concerns, we can uncover the layers of meaning that have made "Adlestrop" a enduring fixture in the canon of English literature.

Historical Context and Biographical Significance

To fully appreciate "Adlestrop," one must consider the historical and personal context in which it was written. Composed in 1914, just before the outbreak of World War I, the poem captures a moment of peace that would soon be shattered by global conflict. Thomas, who would tragically lose his life in the war in 1917, imbues the poem with a sense of nostalgia and a celebration of the English countryside that would resonate deeply with readers in the post-war years.

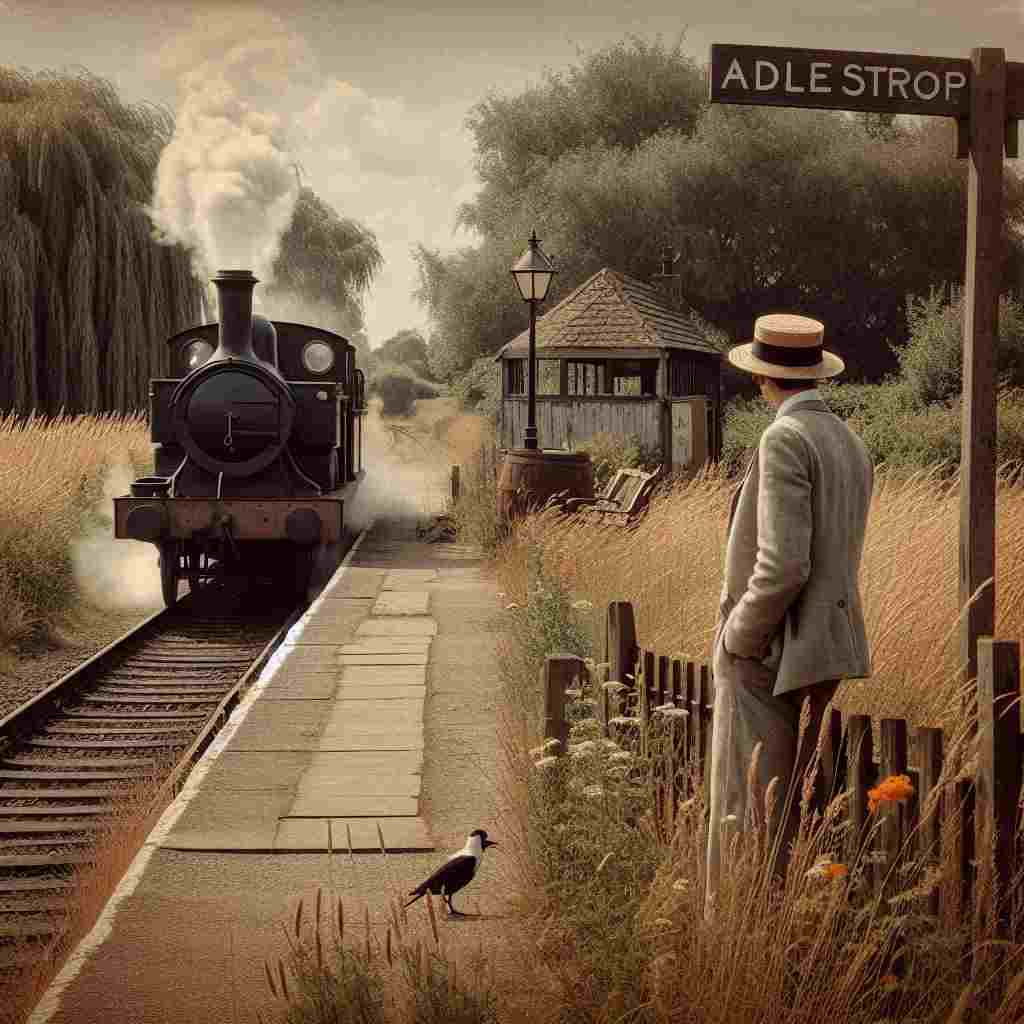

The poem's setting, a real village in Gloucestershire where Thomas's train made an unscheduled stop, serves as a microcosm of rural England. This brief encounter with Adlestrop became, for Thomas, a crystallization of national identity and natural beauty, preserved in amber by his poetic craftsmanship.

Structure and Form

"Adlestrop" consists of four quatrains with an ABAB rhyme scheme, a form that echoes the traditional ballad stanza. This choice of structure lends the poem a sense of simplicity and directness that belies its complex emotional resonance. The regular meter, predominantly iambic tetrameter, creates a rhythm reminiscent of a train's steady movement, subtly reinforcing the poem's central narrative device.

However, Thomas employs subtle variations in this rhythm, particularly in the first line of each stanza, which often begins with a stressed syllable. This technique, known as a trochaic substitution, serves to emphasize key words and creates a sense of immediacy, as in the opening "Yes" and the repeated "And" that begins the third and fourth stanzas.

Imagery and Sensory Detail

The power of "Adlestrop" lies in its vivid, sensory evocation of a specific moment in time. Thomas's imagery is precise and evocative, drawing the reader into the scene with remarkable economy of language. The "heat" of the afternoon, the hissing steam, and the cleared throat create a multi-sensory tableau that brings the railway platform to life.

The progression of imagery from the man-made to the natural world is particularly noteworthy. Beginning with the train and platform, Thomas gradually shifts focus to the surrounding flora: "willows, willow-herb, and grass, / And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry." This transition mirrors the speaker's own shift in attention, as the unexpected stop allows for a moment of communion with nature.

The culmination of this imagery comes in the final stanza, where the solitary blackbird's song expands to encompass "all the birds / Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire." This auditory image serves as a powerful metaphor for the way a single moment can open up to reveal a broader, more profound experience of place and time.

Themes and Interpretation

At its core, "Adlestrop" is a meditation on memory, perception, and the relationship between humanity and nature. The poem's opening line, "Yes. I remember Adlestrop —," immediately establishes memory as a central concern. The use of the present tense "remember" suggests that this is not merely a recollection, but an active, ongoing process of remembering.

The tension between movement and stillness is another key theme. The express train's unexpected stop creates a liminal space where time seems to pause, allowing for a moment of heightened awareness. This juxtaposition of speed and stillness serves as a metaphor for modern life, suggesting the value of these rare moments of pause and reflection.

The poem also explores the idea of absence and presence. The assertion that "No one left and no one came / On the bare platform" emphasizes the emptiness of the human world, contrasting sharply with the richness of the natural environment. This contrast invites us to consider what we might be missing in our daily rush through life.

Furthermore, "Adlestrop" can be read as a celebration of English rural identity. The specific naming of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire in the final lines roots the poem firmly in the English countryside, while the catalog of native plants creates a distinctly English pastoral scene. In the context of the impending war, this celebration of Englishness takes on an added poignancy.

Language and Poetic Technique

Thomas's use of language in "Adlestrop" is deceptively simple yet highly crafted. The poem's diction is largely monosyllabic, with occasional polysyllabic words like "Unwontedly" and "Gloucestershire" standing out against this backdrop. This simplicity of language contributes to the poem's directness and accessibility, while also mimicking the clarity of the remembered moment.

Repetition plays a crucial role in the poem's effect. The repeated "And" at the beginning of lines serves to build a sense of accumulation, as if the speaker is gradually recalling more details of the scene. The repetition of "Adlestrop" itself — first as a place name, then as "only the name" — emphasizes the power of words to evoke entire worlds of experience.

Thomas's use of enjambment, particularly in the third stanza, creates a sense of continuity that mirrors the expansiveness of the countryside. The run-on lines encourage the reader to move smoothly from one image to the next, reflecting the speaker's widening perception of the scene.

Conclusion

"Adlestrop" stands as a testament to Edward Thomas's skill as a poet and his deep connection to the English landscape. Through its careful construction, evocative imagery, and thematic depth, the poem transforms a brief, seemingly insignificant moment into a profound meditation on memory, nature, and national identity.

The enduring appeal of "Adlestrop" lies in its ability to capture a universal experience — that of unexpected beauty found in ordinary moments — while simultaneously evoking a specific time and place. As readers, we are invited to share in the speaker's moment of heightened awareness, to hear the blackbird's song echoing across the counties, and to reflect on our own experiences of unexpected stillness in a rushing world.

In the century since its composition, "Adlestrop" has become more than just a poem; it has become a cultural touchstone, a shorthand for a certain kind of English pastoral experience. Its influence can be traced through subsequent generations of poets, and its lines continue to resonate with readers who may never have set foot in Gloucestershire.

Ultimately, "Adlestrop" reminds us of the power of poetry to preserve moments, to make the fleeting permanent, and to find profound meaning in the simplest of experiences. In doing so, it secures Edward Thomas's place as one of the most significant voices in 20th-century English poetry.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!