Thou whom chance may hither lead

Robert Burns

1759 to 1796

Thou whom chance may hither lead,

Be thou clad in russet weed,

Be thou deck'd in silken stole,

Grave these maxims on thy soul.

Life is but a day at most,

Sprung from night, in darkness lost;

Day, how rapid in its flight--

Day, how few must see the night;

Hope not sunshine every hour,

Fear not clouds will always lower.

Happiness is but a name,

Make content and ease thy aim.

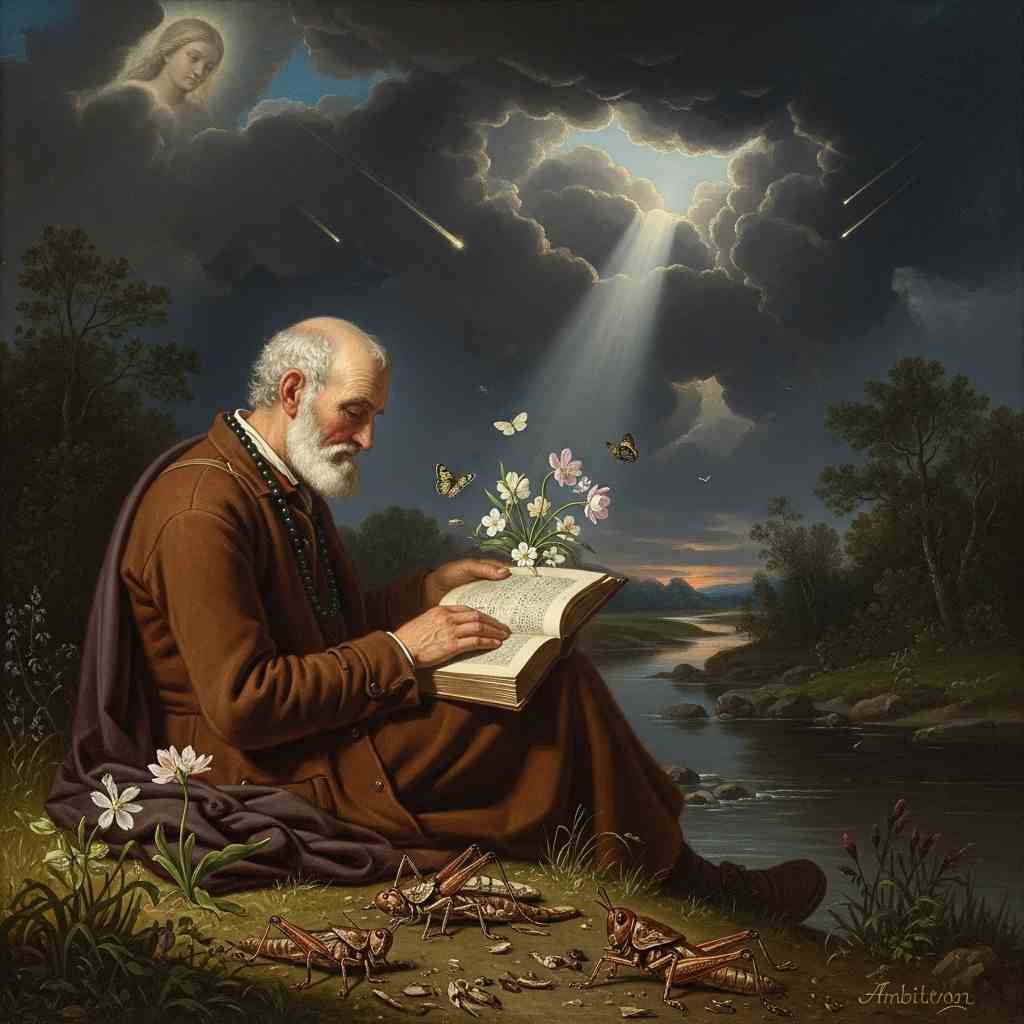

Ambition is a meteor gleam;

Fame, a restless idle dream:

Pleasures, insects on the wing

Round Peace, the tenderest flower of Spring;

Those that sip the dew alone,

Make the butterflies thy own;

Those that would the bloom devour,

Crush the locusts--save the flower.

For the future be prepar'd,

Guard wherever thou canst guard;

But, thy utmost duly done,

Welcome what thou canst not shun.

Follies past, give thou to air,

Make their consequence thy care:

Keep the name of man in mind,

And dishonour not thy kind.

Reverence with lowly heart

Him whose wondrous work thou art;

Keep His goodness still in view,

Thy trust--and thy example, too.

Stranger, go! Heaven be thy guide!

Quod the Beadsman on Nithside.

Robert Burns's Thou whom chance may hither lead

Robert Burns, Scotland’s national poet, remains one of the most enduring voices of the 18th century, celebrated for his lyrical intensity, philosophical depth, and keen observation of human nature. His poem “Thou whom chance may hither lead”—sometimes referred to by its opening line or as “The Beadsman’s Advice”—is a meditation on life’s transience, the folly of ambition, and the necessity of moral fortitude. Though less famous than “To a Mouse” or “Auld Lang Syne,” this poem encapsulates Burns’ characteristic blend of rustic wisdom, moral instruction, and emotional resonance.

This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its literary devices, central themes, and emotional impact. Additionally, we will consider Burns’ philosophical influences, possible biographical connections, and how the poem fits within the broader tradition of memento mori literature.

Historical and Cultural Context

The Scottish Enlightenment and Religious Sentiment

Burns wrote during the Scottish Enlightenment, a period marked by intellectual flourishing in philosophy, science, and literature. Thinkers like David Hume and Adam Smith emphasized reason, empirical inquiry, and moral philosophy. Yet, Burns’ work also reflects the lingering influence of Calvinism, with its focus on human frailty, divine providence, and moral accountability.

The poem’s didactic tone resembles Puritanical moralizing, yet its emphasis on contentment and the rejection of worldly ambition also aligns with Stoic and Epicurean thought. The speaker—identified in the final line as a “Beadsman” (a religious hermit or almsman)—dispenses wisdom that is both practical and spiritual, suggesting a synthesis of Enlightenment rationality and traditional piety.

Rural Scotland and Social Commentary

Burns was deeply rooted in rural Ayrshire, and his poetry often reflects the struggles and values of peasant life. The poem’s opening lines—“Be thou clad in russet weed, / Be thou deck'd in silken stole”—address both the poor (“russet weed,” coarse clothing) and the wealthy (“silken stole”), implying that moral truths transcend class. This egalitarian perspective was radical in an era of rigid social hierarchies, reflecting Burns’ democratic sympathies.

The reference to “Nithside” (the River Nith in Dumfriesshire, where Burns spent his later years) grounds the poem in a specific Scottish landscape, reinforcing Burns’ connection to his homeland even as he speaks in universal terms.

Literary Devices and Structure

Aphoristic Style and Didacticism

The poem is composed in a series of maxims, reminiscent of classical moralists like Horace or Ecclesiastes. Lines such as “Life is but a day at most” and “Happiness is but a name” distill complex philosophical ideas into concise, memorable phrases. This aphoristic style lends the poem the quality of a sermon or proverb collection, reinforcing its instructional purpose.

Metaphor and Symbolism

Burns employs vivid natural imagery to convey abstract concepts:

-

Life as a fleeting day: “Sprung from night, in darkness lost” evokes the brevity of existence, recalling Shakespeare’s “life’s but a walking shadow” (Macbeth).

-

Ambition as a “meteor gleam”: This metaphor suggests that fame is transient and illusory, burning brightly but vanishing quickly.

-

Pleasures as “insects on the wing”: Some pleasures (“those that sip the dew alone”) are harmless, like butterflies, while others (“those that would the bloom devour”) are destructive, like locusts. The imagery reinforces the need for discernment in seeking joy.

Imperative Tone and Direct Address

The poem’s urgency comes from its repeated commands (“Hope not,” “Fear not,” “Make content and ease thy aim”). The direct address (“Thou whom chance may hither lead”) creates an intimate, almost confessional tone, as if the reader is being personally admonished by a wise elder.

Contrast and Paradox

Burns balances opposing ideas to underscore life’s uncertainties:

-

“Hope not sunshine every hour, / Fear not clouds will always lower” advocates emotional equilibrium.

-

“For the future be prepar'd, / Guard wherever thou canst guard; / But thy utmost duly done, / Welcome what thou canst not shun” combines prudence with acceptance, echoing Stoic philosophy.

Themes and Philosophical Undercurrents

The Transience of Life

The poem’s opening lines establish its central theme: life’s ephemerality. The metaphor of life as a single day (“how rapid in its flight”) underscores human mortality, aligning with the memento mori tradition. Unlike the Romantic glorification of emotion, Burns’ perspective is sobering yet not despairing—he advocates not resignation but mindful living.

The Folly of Ambition and Fame

Burns dismisses ambition as a “meteor gleam” and fame as a “restless idle dream,” echoing classical and biblical warnings against vanity (cf. Ecclesiastes: “All is vanity”). This skepticism toward worldly success reflects Burns’ own conflicted relationship with fame—he enjoyed literary acclaim but remained financially struggling and disillusioned by aristocratic patronage.

Contentment and Moral Duty

The poem’s ethical core lies in its advocacy of contentment (“Make content and ease thy aim”) and moral responsibility (“Keep the name of man in mind, / And dishonour not thy kind”). The injunction to “Reverence with lowly heart / Him whose wondrous work thou art” suggests humility before divine creation, blending Deistic wonder with Christian piety.

Stoic Resignation and Active Virtue

Burns’ advice—“Welcome what thou canst not shun”—parallels Stoic teachings on accepting fate while striving for virtue. The poem does not advocate passivity but balanced action: prepare for the future, guard against folly, yet accept inevitable hardships.

Emotional Impact and Universal Resonance

Despite its didacticism, the poem avoids preachiness through its lyrical beauty and empathetic tone. The imagery of fleeting days and fragile flowers evokes melancholy, while the final benediction (“Stranger, go! Heaven be thy guide!”) offers solace. The Beadsman’s voice is weary yet compassionate, a sage who has witnessed life’s trials and dispenses hard-won wisdom.

Burns’ ability to merge rustic simplicity with profound insight ensures the poem’s enduring appeal. Its themes—mortality, humility, the search for meaning—are timeless, resonating across cultures and eras.

Comparative and Biographical Perspectives

Comparisons with Other Works

-

Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”: Both poems meditate on mortality and the equality of death, though Gray’s tone is more elegiac, while Burns’ is pragmatic.

-

Wordsworth’s “The World Is Too Much With Us”: Both critique materialism, but Burns’ solution is moral discipline rather than Wordsworth’s Romantic communion with nature.

Biographical Echoes

Burns’ own life—marked by financial instability, tumultuous relationships, and bouts of depression—lends authenticity to the poem’s warnings against ambition and its plea for contentment. His later years, spent in relative isolation in Dumfries, may have inspired the Beadsman’s voice—a figure detached from worldly strife yet deeply engaged in moral reflection.

Conclusion: A Testament to Burns’ Moral and Artistic Vision

“Thou whom chance may hither lead” exemplifies Burns’ ability to distill profound wisdom into accessible, evocative verse. Its blend of rustic imagery, classical philosophy, and religious humility creates a work that is both instructive and deeply moving. While lesser-known than his more rollicking or sentimental pieces, this poem captures the essence of Burns’ worldview: a clear-eyed recognition of life’s brevity, tempered by a call to live with dignity, purpose, and quiet joy.

In an age of relentless ambition and fleeting pleasures, Burns’ words remain a poignant reminder of what endures: not fame or wealth, but the quiet cultivation of virtue and contentment. The Beadsman’s advice, though centuries old, still whispers across time, urging us to “Keep His goodness still in view”—a guiding light in the darkness of an uncertain world.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more