The Treadmill Song

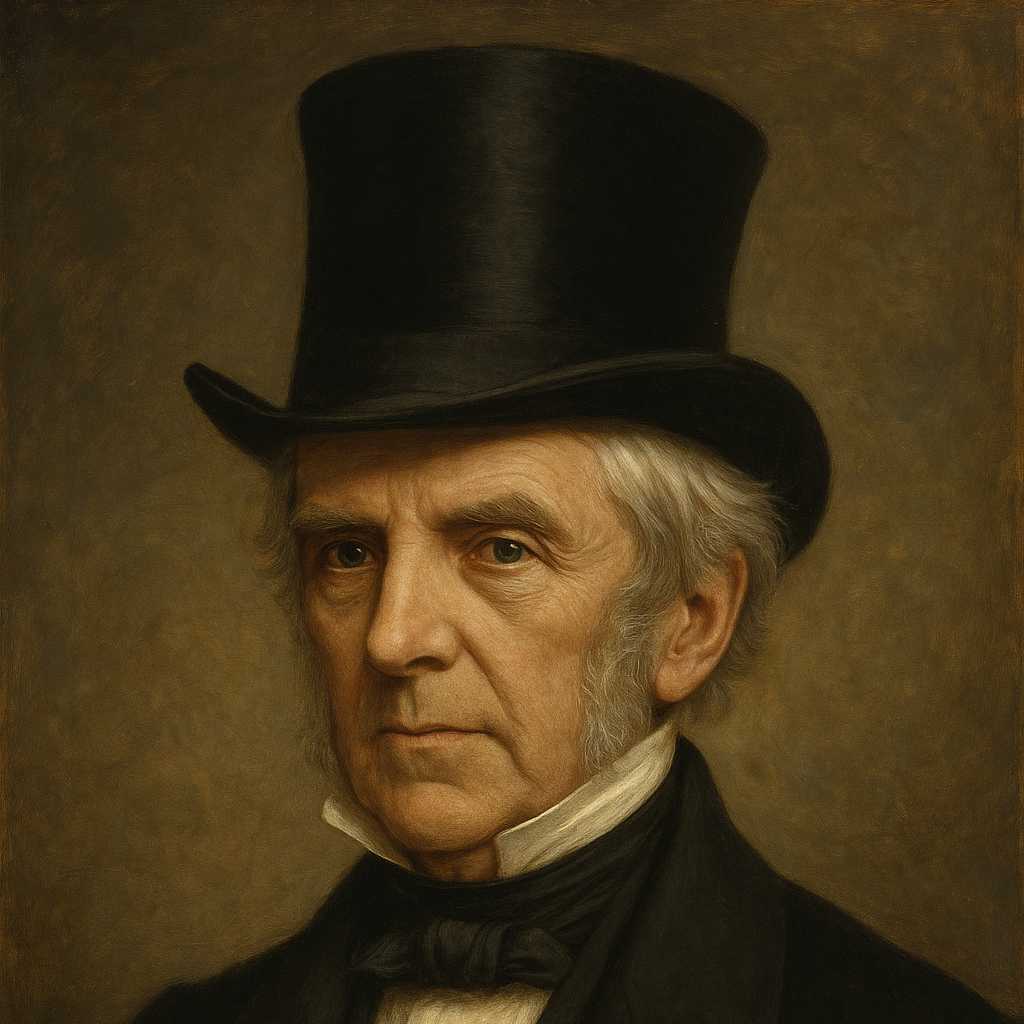

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

1809 to 1894

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

The stars are rolling in the sky,

The earth rolls on below,

And we can feel the rattling wheel

Revolving as we go.

Then tread away, my gallant boys,

And make the axle fly;

Why should not wheels go round about,

Like planets in the sky?

Wake up, wake up, my duck-legged man,

And stir your solid pegs

Arouse, arouse, my gawky friend,

And shake your spider legs;

What though you're awkward at the trade,

There's time enough to learn,—

So lean upon the rail, my lad,

And take another turn.

They've built us up a noble wall,

To keep the vulgar out;

We've nothing in the world to do

But just to walk about;

So faster, now, you middle men,

And try to beat the ends,—

It's pleasant work to ramble round

Among one's honest friends.

Here, tread upon the long man's toes,

He sha'n't be lazy here,—

And punch the little fellow's ribs,

And tweak that lubber's ear,—

He's lost them both,—don't pull his hair,

Because he wears a scratch,

But poke him in the further eye,

That is n't in the patch.

Hark! fellows, there's the supper-bell,

And so our work is done;

It's pretty sport,—suppose we take

A round or two for fun!

If ever they should turn me out,

When I have better grown,

Now hang me, but I mean to have

A treadmill of my own!

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.'s The Treadmill Song

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.’s The Treadmill Song is a deceptively jaunty poem that masks a biting critique of 19th-century penal labor and the dehumanizing nature of repetitive toil. At first glance, the poem’s rollicking rhythm and playful tone suggest a lighthearted work song, but beneath its surface lies a scathing indictment of institutionalized punishment and the illusion of productivity. Through its historical context, literary devices, and thematic depth, The Treadmill Song reveals Holmes’s keen social awareness and his ability to blend satire with genuine pathos.

Historical and Cultural Context: The Treadmill as Symbol of Oppression

To fully appreciate The Treadmill Song, one must understand the treadmill’s role in early 19th-century penal systems. Invented in 1818 by Sir William Cubitt as a method of hard labor for prisoners, the treadmill was a large, wheel-like device that inmates would step on endlessly, often grinding grain or pumping water—though sometimes serving no purpose other than sheer punishment. The device was both physically grueling and psychologically monotonous, reducing human beings to cogs in an unfeeling machine.

Holmes, a physician and polymath, was deeply attuned to social issues, and his poem reflects the absurdity and cruelty of such forced labor. The treadmill was not merely a tool of discipline but a metaphor for the Industrial Revolution’s dehumanizing effects, where workers—whether prisoners or factory laborers—were subjected to mindless, repetitive tasks. The poem’s cheerful tone thus becomes deeply ironic, highlighting the disconnect between the authorities’ justifications for the treadmill and the grim reality endured by those forced to operate it.

Literary Devices: Irony, Persona, and Dark Humor

Holmes employs a striking contrast between form and content, using a singsong rhythm that mimics the relentless motion of the treadmill itself. The poem’s speaker adopts the voice of a jovial overseer or fellow prisoner, urging his companions to “tread away” as if they were engaged in merry sport rather than punitive labor. This ironic cheerfulness amplifies the horror of the situation, much like the forced jollity of a chain-gang work song.

The poem’s dark humor emerges in lines such as:

"What though you're awkward at the trade, / There's time enough to learn,—"

Here, the speaker’s encouragement is laced with grim fatalism—there is nothing but time in this endless cycle of exertion. The treadmill is not a skill to be mastered but a sentence to be endured.

Another notable device is the dehumanizing language used to describe the prisoners:

"Wake up, wake up, my duck-legged man, / And stir your solid pegs"

The reduction of limbs to “pegs” and “spider legs” underscores how the system strips individuals of their humanity, rendering them mere mechanical parts. The poem’s middle stanzas, where the prisoners jostle and poke one another, suggest both camaraderie and petty cruelty—a microcosm of how oppression breeds both solidarity and resentment among the oppressed.

Themes: Confinement, False Camaraderie, and the Illusion of Purpose

1. The Futility of Forced Labor

The treadmill, by design, accomplishes nothing beyond its own operation. Holmes underscores this futility in the lines:

"We've nothing in the world to do / But just to walk about;"

The prisoners are not producing anything of value; their labor is performative, meant only to satisfy societal demands for punishment. This mirrors critiques of modern bureaucratic labor, where tasks are often created to justify systems rather than serve meaningful ends.

2. The Delusion of Camaraderie

The speaker’s repeated exhortations to “take another turn” and “ramble round / Among one’s honest friends” suggest a forced sense of community. Yet the interactions between prisoners—stepping on toes, punching ribs, tweaking ears—reveal underlying aggression and frustration. The treadmill does not foster true solidarity but rather a desperate, almost manic, attempt to make light of suffering.

3. The Stockholm Syndrome of Institutionalization

The poem’s closing lines are particularly chilling:

"If ever they should turn me out, / When I have better grown, / Now hang me, but I mean to have / A treadmill of my own!"

Here, the speaker has internalized his oppression to such an extent that he fantasizes about replicating it. This echoes real-world cases where long-term prisoners struggle to adapt to freedom, or where abused individuals perpetuate cycles of violence. Holmes suggests that institutionalization warps the psyche, making the oppressed complicit in their own subjugation.

Comparative Analysis: Holmes and the Satirical Tradition

Holmes’s poem aligns with the tradition of satirical works that critique social institutions through irony. Like Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal, which couches horrific suggestions in reasonable language, The Treadmill Song presents its critique through exaggerated enthusiasm. Similarly, Charles Dickens’ depictions of debtors’ prisons and workhouses in Little Dorrit and Oliver Twist expose the cruelty of punitive systems under the guise of moral reform.

A more direct parallel can be drawn with the prison poetry of Oscar Wilde, particularly The Ballad of Reading Gaol, which also explores the psychological toll of incarceration. However, where Wilde’s poem is solemn and tragic, Holmes’s is bitingly sardonic, using humor as a weapon against injustice.

Philosophical and Psychological Dimensions

The treadmill serves as a potent metaphor for existential absurdity—an endless, meaningless task imposed by an indifferent system. Philosophers like Albert Camus might see in it a reflection of Sisyphus’s eternal struggle, though Holmes’s prisoners lack even the dignity of rebellion. Instead, they are trapped in a cycle of forced enthusiasm, their compliance a form of psychological survival.

From a psychological standpoint, the poem illustrates the effects of learned helplessness—the phenomenon where individuals, subjected to uncontrollable adversity, begin to accept their suffering as inevitable. The prisoners’ joking demeanor is a coping mechanism, a way to reclaim agency through dark humor.

Emotional Impact: The Horror Beneath the Levity

What makes The Treadmill Song so unsettling is its tonal dissonance. The poem’s jaunty rhythm invites readers to almost overlook its bleak subject matter, much like society overlooks the suffering of the incarcerated. Only upon closer reading does the full horror emerge: these men are not just laboring but being broken, their spirits eroded by pointless exertion.

The final declaration—"I mean to have / A treadmill of my own!"—is a masterstroke of irony. It suggests not empowerment but complete psychological colonization by the system. The prisoner has absorbed his oppression so thoroughly that he now desires to replicate it. This ending forces readers to confront the insidious nature of institutional control, leaving them with a sense of unease that lingers far beyond the poem’s last line.

Conclusion: A Timeless Critique of Dehumanization

Though rooted in the 19th century, The Treadmill Song remains disturbingly relevant. Its themes resonate in modern discussions of mass incarceration, exploitative labor practices, and the psychological effects of institutionalization. Holmes’s genius lies in his ability to cloak profound social criticism in playful verse, making his message both accessible and unforgettable.

The poem challenges us to question systems that reduce human beings to mere functionaries of their own punishment. It asks: When does discipline become cruelty? When does routine become imprisonment? And at what point do the oppressed begin to enforce their own chains?

In the end, The Treadmill Song is not just a historical artifact but a timeless warning—a reminder that the most insidious cages are those we no longer see.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!