A Thunderstorm in Town

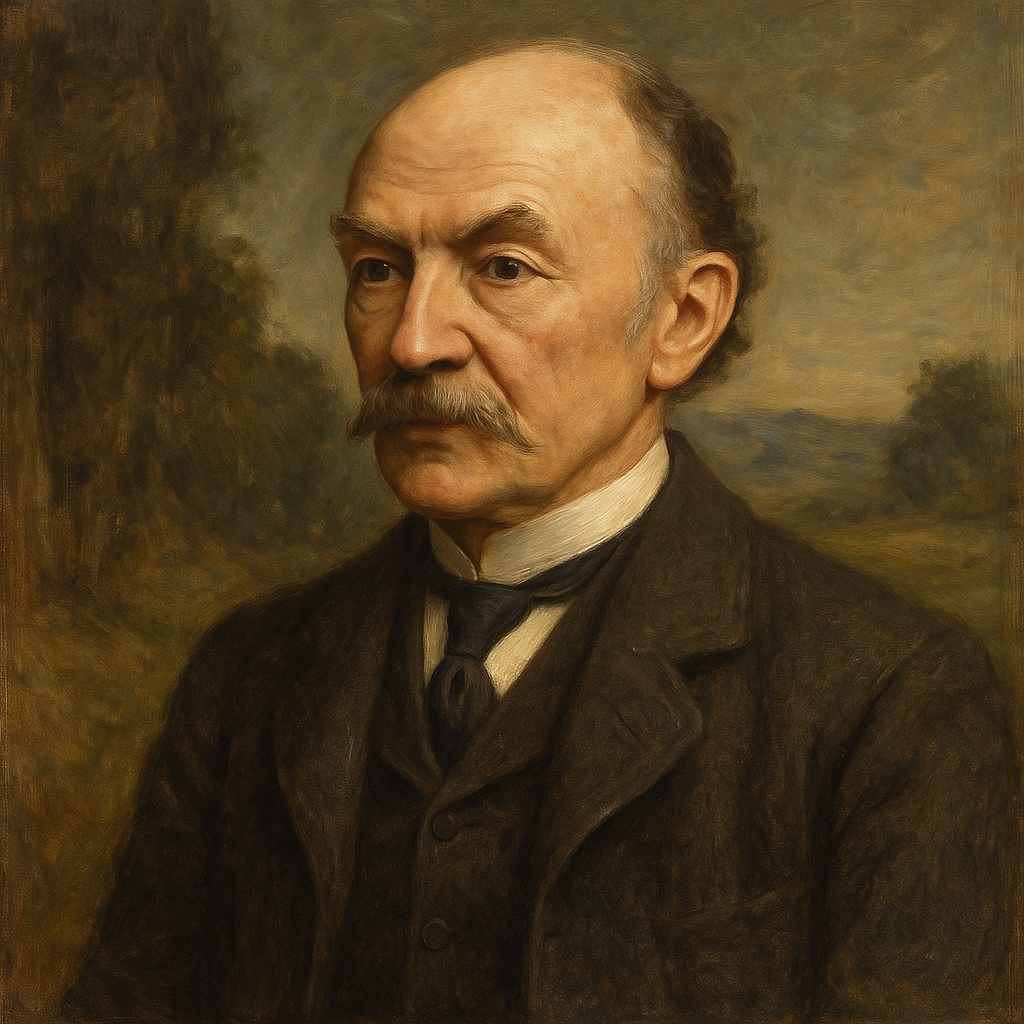

Thomas Hardy

1840 to 1928

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

(A Reminiscence: 1893)

She wore a new "terra-cotta" dress,

And we stayed, because of the pelting storm,

Within the hansom's dry recess,

Though the horse had stopped; yea, motionless

We sat on, snug and warm.

Then the downpour ceased, to my sharp sad pain

And the glass that had screened our forms before

Flew up, and out she sprang to her door:

I should have kissed her if the rain

Had lasted a minute more.

Thomas Hardy's A Thunderstorm in Town

Thomas Hardy’s A Thunderstorm in Town is a brief yet emotionally charged poem that captures a fleeting moment of romantic possibility, abruptly lost. Written in 1893 and subtitled A Reminiscence, the poem reflects Hardy’s characteristic preoccupation with missed opportunities, the cruel whims of fate, and the quiet tragedies of everyday life. Despite its brevity, the poem is rich in historical and cultural subtext, employing vivid imagery, subtle irony, and a poignant narrative structure to convey its themes. This essay will explore the poem’s historical context, literary devices, emotional resonance, and thematic depth, while also considering its place within Hardy’s broader body of work.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate A Thunderstorm in Town, one must situate it within the social mores and technological landscape of late Victorian England. The poem references a hansom cab—a two-wheeled horse-drawn carriage popular in the 19th century—which serves as the intimate setting for this fleeting encounter. The hansom, with its enclosed yet public nature, was a space where social propriety and private desire could uncomfortably coexist. The woman’s "terra-cotta" dress—a reddish-brown hue fashionable at the time—immediately grounds the poem in a specific aesthetic moment, reinforcing the realism that Hardy often favored in his poetry.

The year 1893 is also significant in Hardy’s personal life. By this time, he had already published major novels such as Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) and Jude the Obscure (1895), works that challenged Victorian sexual morality and social hypocrisy. Though primarily known as a novelist, Hardy increasingly turned to poetry after the public outcry against Jude the Obscure, which he claimed discouraged him from writing further fiction. Many of his poems, including this one, explore themes of romantic regret and the cruel ironies of timing—an obsession that may have been influenced by his own complex relationships, including his troubled marriage to Emma Gifford.

Literary Devices and Narrative Technique

Hardy’s poem is a masterclass in conciseness, using precise imagery and controlled pacing to evoke a sense of abrupt loss. The poem unfolds in two distinct movements: the first five lines establish the scene, while the last five deliver the emotional punch.

1. Imagery and Symbolism

The "terra-cotta" dress is not merely a visual detail but a symbol of warmth and earthiness, contrasting with the cold, impersonal "pelting storm" outside. The storm itself functions as both a literal and metaphorical device—it creates a temporary shelter, forcing the two figures into proximity, yet its sudden cessation disrupts what might have been a moment of intimacy. The "glass that had screened our forms before" is another potent image, suggesting both protection and separation. The glass acts as a barrier, not just from the rain but from social propriety; once it is lifted, so too is the fleeting illusion of privacy.

2. Irony and Narrative Twist

The poem hinges on a moment of cruel irony: the speaker laments not the storm itself but its end—"to my sharp sad pain". The rain, which initially seemed an inconvenience, becomes the very condition that might have permitted a romantic advance. The abruptness of the woman’s departure ("out she sprang to her door") underscores the suddenness of lost opportunity, a theme Hardy revisits frequently in his work (e.g., The Convergence of the Twain, where fate orchestrates disaster with chilling indifference).

3. Temporal Compression and Suspense

Hardy manipulates time masterfully. The phrase "We sat on, snug and warm" suggests a suspended moment, a pocket of time where societal rules might relax. Yet this suspension is shattered by the rapid sequence of the storm’s end, the glass flying up, and the woman’s exit—all within two lines. The final lament ("I should have kissed her if the rain / Had lasted a minute more") is devastating in its specificity. The hypothetical "minute" becomes a measure of life’s cruel precision in denying happiness.

Themes: Fate, Regret, and Social Constraint

1. The Capriciousness of Fate

Hardy was deeply influenced by the philosophical pessimism of Schopenhauer and the classical notion of tragic fate. In A Thunderstorm in Town, chance governs human emotion: the rain’s duration is arbitrary, yet it dictates the speaker’s romantic prospects. There is a bitter humor in how something as mundane as weather can alter the course of desire. This aligns with Hardy’s larger worldview, where humans are subject to indifferent cosmic forces—a theme evident in poems like Hap, where he rails against a universe that delivers suffering at random.

2. The Agony of Missed Opportunity

The speaker’s regret is palpable, yet it is rendered with restraint. Unlike a more melodramatic treatment of lost love, Hardy’s approach is understated, making the emotion more piercing. The conditional phrasing ("I should have kissed her") suggests self-reproach, as though the speaker is replaying the moment, tormenting himself with what might have been. This introspective regret is a hallmark of Hardy’s verse, seen also in The Voice, where memory and longing intertwine painfully.

3. Social Restriction and the Unspoken

The poem subtly critiques Victorian social conventions. The hansom cab, though a private space, is still a public conveyance—any romantic gesture would risk impropriety. The woman’s swift exit ("sprang to her door") suggests an awareness of societal judgment, as though she senses the danger of lingering. The glass, once a shield from the storm, becomes a metaphor for the invisible barriers of decorum that prevent genuine connection.

Comparative Analysis: Hardy’s Other Works

A Thunderstorm in Town shares thematic DNA with much of Hardy’s poetry. In Neutral Tones, for instance, a failed romantic encounter is framed in bleak, naturalistic terms, with love decaying like "grayish leaves". Similarly, The Going laments the irreversible passage of time and lost chances, though with greater elegiac weight. What distinguishes A Thunderstorm in Town is its almost anecdotal quality—it feels like a snatched memory, a minor yet haunting moment of near-intimacy.

Comparisons might also be drawn to the novels. In Far from the Madding Crowd, Bathsheba and Boldwood’s missed connections echo the same cruel timing, while The Mayor of Casterbridge revolves around irreversible decisions made in fleeting moments. Hardy’s work consistently suggests that human lives are shaped not by grand designs but by small, uncontrollable contingencies.

Philosophical and Emotional Resonance

The poem’s power lies in its universality. Who has not experienced a moment where circumstance—a traffic light, a phone call, a change in weather—altered the course of an encounter? Hardy elevates this mundane frustration into a miniature tragedy, demonstrating his belief that life’s deepest sorrows often arise from its smallest denials.

The emotional impact is heightened by the poem’s brevity. Unlike a sprawling narrative, this concise form mimics the abruptness of the moment itself. The final lines hang in the air, unresolved, leaving the reader to imagine the weight of that unlived minute. It is a testament to Hardy’s skill that such a short poem can evoke such profound melancholy.

Conclusion

A Thunderstorm in Town is a masterful example of Hardy’s ability to compress vast emotional and philosophical depth into a few precise lines. Through its careful imagery, ironic structure, and themes of fate and regret, the poem captures the exquisite pain of missed connection. It is a work that resonates beyond its Victorian context, speaking to anyone who has felt the sting of almost. In the grand tapestry of Hardy’s oeuvre, it may be a minor piece, but like the storm it describes, its brevity only intensifies its force.

Hardy reminds us that poetry’s greatest strength is its ability to freeze time—to immortalize those fleeting instants that, however small, haunt us forever. In this, A Thunderstorm in Town is not just a reminiscence but a timeless meditation on the fragility of human desire in the face of an indifferent universe.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!