My Youth

W. H. Davies

1871 to 1940

My youth was my old age,

Weary and long;

It had too many cares

To think of song;

My moulting days all came

When I was young.

Now, in life's prime, my soul

Comes out in flower;

Late, as with Robin, comes

My singing power;

I was not born to joy

Till this late hour.

W. H. Davies's My Youth

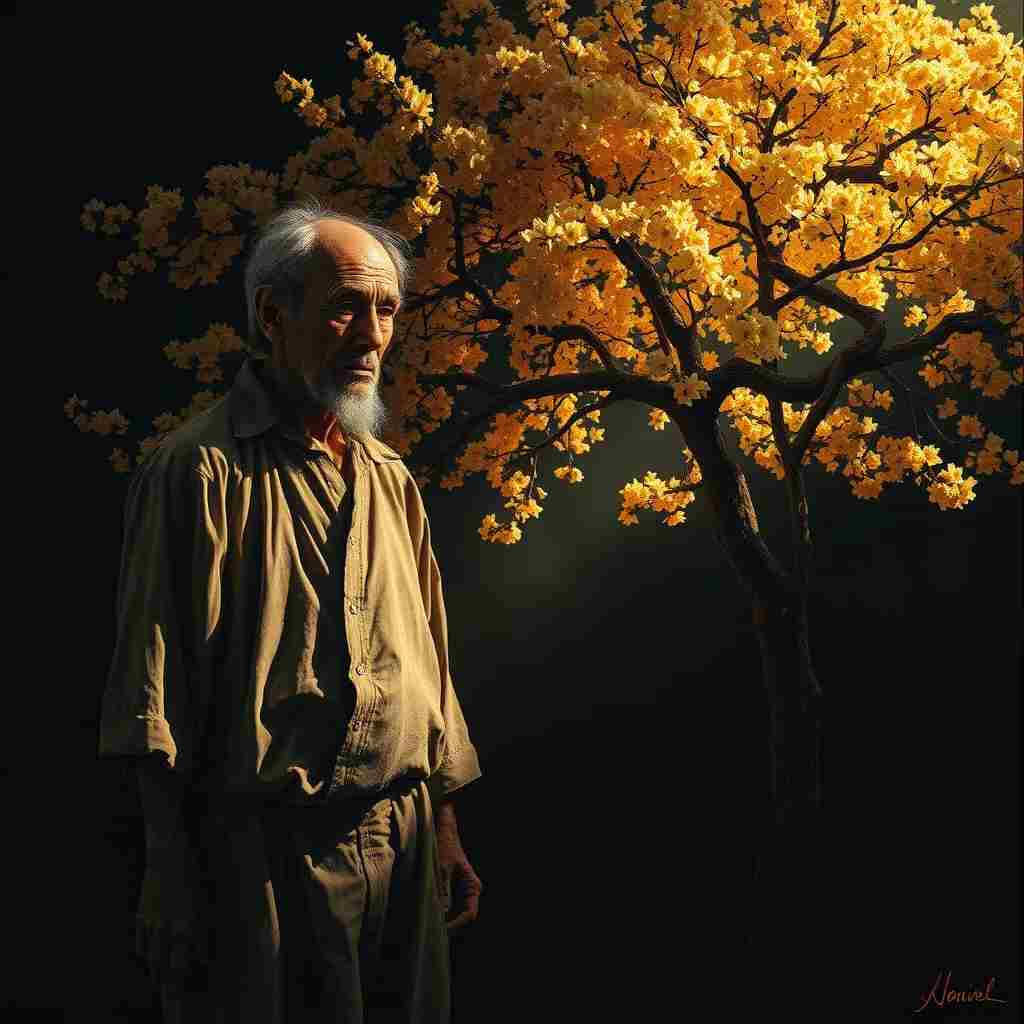

W. H. Davies’ My Youth is a compact yet profoundly contemplative poem that inverts conventional notions of aging and vitality. At first glance, the poem appears simple, even slight, but upon closer examination, it reveals a complex meditation on time, suffering, and the delayed blossoming of creative and emotional fulfillment. Davies, a poet often associated with the Georgian era and known for his reflections on nature, hardship, and transcendence, here distills a lifetime of experience into six concise couplets. The poem’s brevity belies its depth, as Davies explores the paradox of feeling aged in youth and rejuvenated in maturity. Through careful attention to diction, imagery, and structure, the poem challenges linear perceptions of time and personal growth, ultimately suggesting that fulfillment is not bound by chronology but by the soul’s readiness to embrace joy.

Historical and Biographical Context

To fully appreciate My Youth, one must consider Davies’ own life, which was marked by hardship, transience, and eventual literary recognition. Born in 1871 in Newport, Wales, Davies endured a difficult childhood, losing his father early and being raised by his mother and grandparents. His youth was not one of carefree innocence but of labor and instability—he worked as an apprentice, lived as a tramp, and even lost a leg in a train-hopping accident in his twenties. These experiences undoubtedly shaped his perception of youth as a period of weariness rather than exuberance.

Davies’ literary career began late; his first significant collection, The Soul’s Destroyer (1905), was published when he was in his mid-thirties, and it was only after gaining the patronage of Edward Thomas and other literary figures that he achieved wider recognition. This trajectory mirrors the sentiment of My Youth, where Davies suggests that his true creative and emotional flowering came not in conventional youth but in later years. The poem can thus be read as both a personal reflection and a broader commentary on the unpredictability of artistic maturation.

Thematic Analysis: The Inversion of Youth and Age

The poem’s central paradox—that Davies’ youth felt like old age—immediately unsettles the reader’s expectations. Youth is traditionally associated with vitality, hope, and boundless energy, while old age is linked to weariness and reflection. Yet Davies subverts this binary, presenting a vision of youth burdened by “too many cares / To think of song.” The phrase “my moulting days all came / When I was young” is particularly striking, as “moulting” suggests a shedding of feathers or skin—an image of vulnerability and transition typically associated with aging or seasonal decline. By situating this process in his youth, Davies implies that his early years were marked by loss and exhaustion rather than growth.

Conversely, the poem’s second stanza presents maturity as a time of unexpected flourishing: “Now, in life’s prime, my soul / Comes out in flower.” The metaphor of flowering is deliberate, evoking organic, cyclical renewal rather than linear decay. The comparison to the robin—a bird often associated with late-season resilience—further reinforces the idea that Davies’ “singing power” arrived tardily but no less beautifully. The final lines, “I was not born to joy / Till this late hour,” carry a quiet triumph, suggesting that joy is not an inherent condition of youth but an achievement won through endurance.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Davies employs a restrained but potent selection of images to convey his inversion of time. The contrast between “weary and long” youth and the soul’s flowering in maturity is underscored by the poem’s structural balance—each stanza mirrors the other in length but opposes it in tone. The first stanza is heavy with words of burden (“weary,” “cares,” “moulting”), while the second lifts into lightness (“flower,” “singing,” “joy”).

The robin, a seemingly minor detail, is a masterstroke of symbolic resonance. In British folklore, the robin is often a symbol of perseverance, appearing even in winter when other birds have fled. Its song is not the exuberant outburst of spring birds but a quieter, steadfast presence. By aligning his own “singing power” with the robin’s late arrival, Davies suggests that his poetic voice is one of hard-worn endurance rather than effortless talent.

The poem’s meter and rhythm also contribute to its emotional impact. The lines are predominantly iambic, creating a steady, almost trudging cadence in the first stanza that mirrors the weight of youth. The second stanza, while maintaining this rhythm, introduces more lyrical phrasing (“Comes out in flower,” “singing power”), subtly enacting the shift from weariness to expression.

Philosophical and Comparative Dimensions

Davies’ meditation on delayed joy invites comparison with other poets who grappled with the relationship between suffering and creativity. John Keats, in Ode to a Nightingale, contrasts the ephemeral beauty of art with the “weariness, the fever, and the fret” of human existence. Like Davies, Keats associates youth with pain rather than idyllic freedom. Similarly, Wordsworth’s Intimations of Immortality posits that childhood is a state of divine insight that fades with age—a near-inverse of Davies’ claim that his true self was only realized later.

Philosophically, the poem resonates with existential and stoic ideas—that meaning is not given but made, often through endurance. Davies does not lament his weary youth so much as he redeems it by asserting that it led to his current flowering. There is a quiet defiance in the final lines, a rejection of the notion that happiness must come early to be valid.

Emotional Impact and Universality

What makes My Youth so enduringly poignant is its universality. Many readers—particularly those who have faced early adversity—will recognize the feeling of having been “old before their time.” Davies articulates a truth that is rarely acknowledged in a culture obsessed with youthful achievement: that some lives do not follow the expected arc, and that fulfillment may arrive on its own schedule.

The poem’s emotional power lies in its understatement. There is no grand declaration of triumph, only a calm assertion that joy, when it comes, is no less sweet for its lateness. This restraint makes the poem all the more moving—it is not a boast but a quiet testimony.

Conclusion: The Triumph of the Late Bloomer

My Youth is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the unpredictability of artistic and personal fulfillment. Through its deft inversion of youth and age, its careful symbolism, and its restrained yet profound emotional resonance, the poem challenges conventional narratives of decline and suggests instead that the soul’s seasons do not always align with the body’s.

Davies, often overshadowed by his more famous contemporaries, here crafts a miniature masterpiece—one that speaks to anyone who has ever felt out of step with time. In doing so, he affirms poetry’s unique ability to capture the complexities of lived experience, offering not just solace but a kind of redemption: the assurance that it is never too late to bloom.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Create a Cloze Exercise

Click the button below to print a cloze exercise of the poem analysis. This exercise is designed for classroom use.