Break, Break, Break

Alfred Lord Tennyson

1809 to 1892

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

Break, break, break,

On thy cold gray stones, O Sea!

And I would that my tongue could utter

The thoughts that arise in me.

O, well for the fisherman's boy,

That he shouts with his sister at play!

O, well for the sailor lad,

That he sings in his boat on the bay!

And the stately ships go on

To their haven under the hill;

But O for the touch of a vanish'd hand,

And the sound of a voice that is still!

Break, break, break

At the foot of thy crags, O Sea!

But the tender grace of a day that is dead

Will never come back to me.

Alfred Lord Tennyson's Break, Break, Break

Introduction

Alfred, Lord Tennyson's "Break, Break, Break" stands as a poignant exemplar of Victorian elegiac poetry, encapsulating the poet's profound struggle with grief and the ineffable nature of loss. Composed in 1835 and published in 1842, the poem is widely believed to be Tennyson's response to the death of his dear friend Arthur Henry Hallam in 1833. Through its masterful use of imagery, sound, and structure, "Break, Break, Break" not only articulates the speaker's personal anguish but also resonates with universal themes of mortality, memory, and the human condition in the face of inexorable time.

Structural and Formal Elements

The poem's structure is deceptively simple, consisting of four quatrains with an ABCB rhyme scheme. This apparent simplicity, however, belies the complexity of emotions and ideas conveyed within its lines. The irregular meter, predominantly anapestic but interspersed with iambs and spondees, creates a rhythm that mimics the erratic breaking of waves and the uneven cadence of grief-stricken thoughts.

The title and opening line, "Break, break, break," form an epizeuxis, a rhetorical device involving the immediate repetition of words for emphasis. This repetition serves multiple functions: it echoes the relentless crashing of waves, establishes the poem's somber tone, and hints at the speaker's emotional state—a mind fixated on a single, overwhelming thought.

Imagery and Symbolism

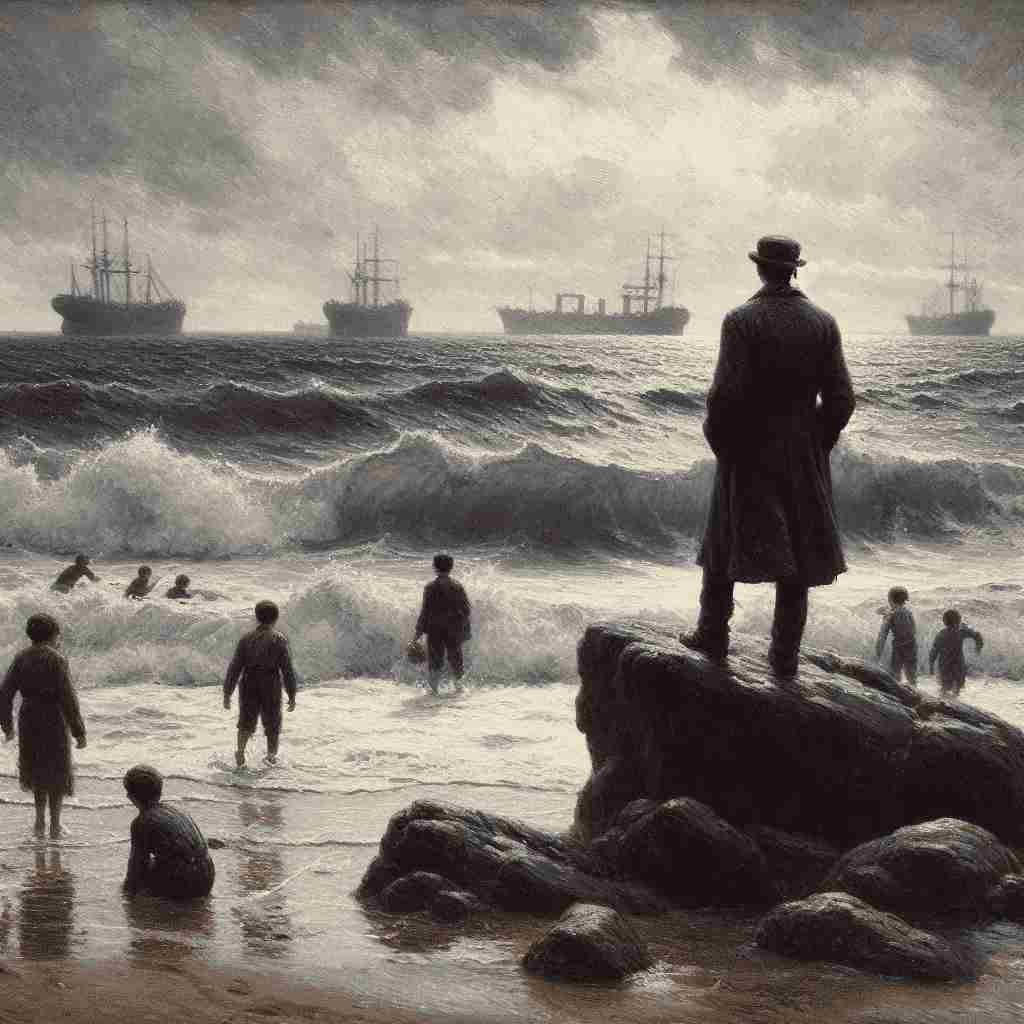

Tennyson's use of natural imagery, particularly the sea, is central to the poem's power. The sea serves as both a literal backdrop and a complex symbol. Its ceaseless motion contrasts sharply with the stillness of death, while its vastness and indifference to human concerns underscore the speaker's sense of isolation and insignificance in the face of loss.

The "cold gray stones" in the first stanza set a bleak, inhospitable scene that reflects the speaker's emotional landscape. This imagery of coldness and grayness recurs throughout Victorian elegiac poetry, often symbolizing the emotional numbness and bleakness that accompany profound grief.

The progression of images from the intimate (stones) to the expansive (sea) to the human (fisherman's boy, sailor lad) and back to the natural world (stately ships, crags) creates a sense of the speaker's mind wandering, unable to escape the gravity of his sorrow despite the life continuing around him.

The Unutterable and the Absent

A central theme of the poem is the inadequacy of language to express profound emotion. The speaker laments in the first stanza, "And I would that my tongue could utter / The thoughts that arise in me." This struggle with articulation is a common motif in elegiac poetry, reflecting the often isolating nature of grief and the limits of human communication in the face of overwhelming loss.

The absent presence of the deceased friend haunts the poem, most explicitly in the third stanza: "But O for the touch of a vanish'd hand, / And the sound of a voice that is still!" These lines not only evoke the specific, tangible aspects of the lost companion but also highlight the permanence of the loss. The use of synecdoche here—the hand and voice representing the whole person—intensifies the sense of fragmentation and incompleteness left by death.

Juxtaposition and Irony

Tennyson employs stark juxtaposition throughout the poem to heighten its emotional impact. The carefree play of the fisherman's boy and his sister, and the sailor lad singing in his boat, stand in sharp contrast to the speaker's inability to express his sorrow. This juxtaposition serves multiple purposes:

- It emphasizes the speaker's isolation, setting him apart from the everyday joy and activity around him.

- It introduces a note of bitter irony, as the speaker observes life continuing unabated despite his personal tragedy.

- It suggests the cyclical nature of life and death, with new generations obliviously enjoying the world that has become a source of pain for the grieving.

The "stately ships" moving to "their haven under the hill" in the third stanza can be read as a metaphor for death itself—a journey to a final resting place. This image contrasts with the more vigorous activities described earlier, suggesting a gradual movement from life to death that parallels the speaker's emotional journey.

Temporal Aspects and the Irrevocability of Loss

The poem's engagement with time is complex and multifaceted. While the breaking of the waves suggests an endless, cyclical temporality, the speaker's grief is firmly rooted in linear time. The final stanza, with its reference to "the tender grace of a day that is dead," explicitly frames the loss in temporal terms.

The use of the phrase "Will never come back to me" in the final line underscores the irrevocability of the loss. This finality is reinforced by the poem's structure, which returns in its last stanza to the imagery of the first, creating a sense of enclosure that mirrors the speaker's emotional entrapment in his grief.

Sound and Musicality

Despite the speaker's professed inability to "utter" his thoughts, the poem itself is a masterpiece of sound. The alliteration in phrases like "cold gray stones" and "stately ships" creates a sense of cohesion and musicality. The repetition of "O" throughout the poem serves as a kind of keening, a wordless expression of grief that transcends the limitations of language.

The varying length of lines within each stanza contributes to the poem's rhythmic complexity. Shorter lines, particularly those beginning with "O," create pauses that mimic the halting nature of grief-stricken speech and thought.

Conclusion

"Break, Break, Break" stands as a testament to Tennyson's poetic prowess and his ability to transmute personal grief into universal art. Through its intricate interplay of form and content, sound and sense, the poem not only expresses the inexpressible nature of loss but also explores broader themes of human mortality, the passage of time, and the complex relationship between the individual and the natural world.

The poem's enduring power lies in its ability to capture the paradoxical nature of grief—its isolating specificity and its universal resonance. Tennyson's sea, in its ceaseless breaking, becomes a powerful metaphor for the human experience of loss: relentless, transformative, and ultimately uncontainable by words alone.

In the broader context of Victorian poetry, "Break, Break, Break" exemplifies the period's preoccupation with death and remembrance, as well as its tendency to seek solace and meaning in nature. It also foreshadows the more extensive exploration of grief that Tennyson would undertake in "In Memoriam A.H.H.," further cementing his reputation as one of the preeminent elegists of the English language.

Ultimately, "Break, Break, Break" achieves what its speaker claims to find impossible: it gives voice to the ineffable experience of grief, creating a linguistic monument that continues to speak to readers across time, inviting them to contemplate the universal human experiences of love, loss, and the struggle to find meaning in a world marked by impermanence.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more