Ah, Are You Digging On My Grave?

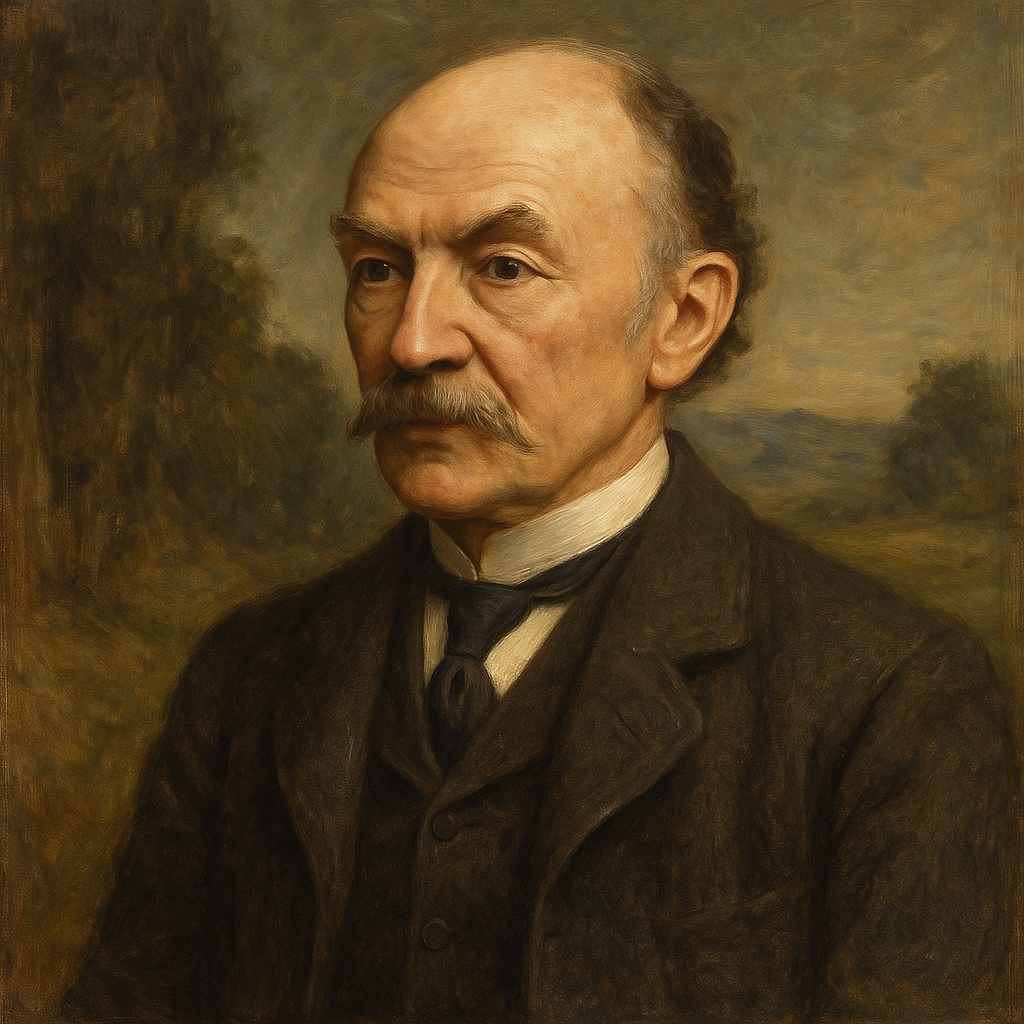

Thomas Hardy

1840 to 1928

"Ah, are you digging on my grave,

My loved one? — planting rue?"

— "No: yesterday he went to wed

One of the brightest wealth has bred.

'It cannot hurt her now,' he said,

'That I should not be true.'"

"Then who is digging on my grave,

My nearest dearest kin?"

— "Ah, no: they sit and think, 'What use!

What good will planting flowers produce?

No tendance of her mound can loose

Her spirit from Death's gin.'"

"But someone digs upon my grave?

My enemy? — prodding sly?"

— "Nay: when she heard you had passed the Gate

That shuts on all flesh soon or late,

She thought you no more worth her hate,

And cares not where you lie.

"Then, who is digging on my grave?

Say — since I have not guessed!"

— "O it is I, my mistress dear,

Your little dog , who still lives near,

And much I hope my movements here

Have not disturbed your rest?"

"Ah yes! You dig upon my grave…

Why flashed it not to me

That one true heart was left behind!

What feeling do we ever find

To equal among human kind

A dog's fidelity!"

"Mistress, I dug upon your grave

To bury a bone, in case

I should be hungry near this spot

When passing on my daily trot.

I am sorry, but I quite forgot

It was your resting place."

Thomas Hardy's Ah, Are You Digging On My Grave?

Introduction

Thomas Hardy's poem "Ah, Are You Digging On My Grave?" stands as a quintessential example of the poet's characteristic blend of irony, pessimism, and keen insight into human nature. Published in 1914 as part of his collection "Satires of Circumstance," this poem encapsulates Hardy's disillusionment with romantic notions of love, loyalty, and remembrance after death. Through a series of increasingly disappointing revelations, Hardy constructs a narrative that systematically dismantles the speaker's—and by extension, the reader's—expectations of posthumous devotion.

Structure and Form

The poem is structured as a dialogue between a deceased woman and various entities she believes might be tending to her grave. This format allows Hardy to create a dramatic irony that builds throughout the piece. The use of six quatrains, each followed by a couplet, creates a rhythmic pattern that mimics the back-and-forth of conversation while also providing a sense of progression and revelation.

The rhyme scheme (ABCCCB DEFFFED) is particularly noteworthy. The triple rhyme in the middle of each stanza creates a sense of insistence or repetition, perhaps echoing the speaker's repeated attempts to find someone who cares for her memory. The couplet at the end of each stanza serves to deliver the punchline or revelation, often with a stark finality that contrasts with the hopeful questioning that precedes it.

Themes and Symbolism

The Transience of Human Relationships

Hardy explores the fleeting nature of human connections, even those we believe to be most enduring. The poem systematically addresses and dismisses potential mourners: a lover, family members, and even an enemy. Each of these human relationships is revealed to be superficial or easily forgotten in the face of death.

The former lover has moved on to a new relationship, prioritizing wealth and the present over loyalty to the deceased. This reflects Hardy's cynical view of romantic love as something easily replaced or superseded by material concerns.

Family members, often considered the closest and most enduring connections, are shown to be equally indifferent. Their rationalization that tending the grave would be useless highlights a pragmatic, almost callous approach to death that strips away any sentimentality.

Even the speaker's enemy, who might be expected to harbor lasting feelings (albeit negative ones), is revealed to have lost interest. This suggests that not only positive emotions but also negative ones are transient in the face of mortality.

The Illusion of Posthumous Importance

Hardy challenges the human desire for lasting importance or remembrance after death. The speaker's repeated questions betray a deep-seated need to believe that she still matters to the living. However, each revelation serves to underscore her growing insignificance in the world of the living.

This theme is particularly poignant given the Victorian era's elaborate mourning customs and the cultural emphasis on remembering the dead. Hardy seems to be suggesting that these practices are more for the benefit of the living than the dead, and that they mask a fundamental indifference to those who have passed.

The Nature of Loyalty and Affection

In a bitter irony, the only being still interested in the grave is the speaker's dog. This revelation initially seems to affirm the idea of "man's best friend" and the superior loyalty of animals compared to humans. However, Hardy subverts even this comforting notion in the final stanza, revealing that the dog's interest is purely self-serving.

This final twist serves multiple purposes. It completes the deconstruction of the speaker's illusions about her lasting importance. It also comments on the nature of loyalty and affection, suggesting that what we perceive as devotion may often be rooted in self-interest or habit rather than genuine emotional connection.

Language and Tone

Hardy's use of language throughout the poem is deceptively simple, belying the complex emotions and ideas at play. The speaker's language is characterized by hope and expectation, with each question framed in a way that suggests a desired answer. This contrasts sharply with the matter-of-fact, often blunt responses she receives.

The tone of the poem shifts subtly as it progresses. It begins with a sense of hopeful curiosity, moves through disappointment and disillusionment, and ends with a bitter irony. This progression is mirrored in the increasingly abrupt and dismissive nature of the responses the speaker receives.

Hardy's choice to have the dog speak in the final stanzas is particularly effective. The dog's articulate speech contrasts with its ultimate animalistic motivation, creating a jarring effect that emphasizes the poem's themes of disillusionment and the stripping away of comforting illusions.

Historical and Biographical Context

To fully appreciate "Ah, Are You Digging On My Grave?", it's crucial to consider Hardy's personal experiences and the broader cultural context of his time. Hardy had a complex relationship with religion and mortality, having lost his faith early in life. This poem reflects his skepticism about traditional religious consolations regarding death and the afterlife.

Moreover, Hardy wrote this poem in his later years, after the death of his first wife, Emma. While it would be overly simplistic to read the poem as a direct reflection of his personal experiences, it's possible to see in it a working through of complex emotions surrounding death, memory, and the nature of human relationships.

The poem also reflects broader cultural shifts of the late Victorian and early Modernist periods. The questioning of traditional values, the growing skepticism towards romantic ideals, and the increasing focus on the psychological complexities of human behavior are all evident in Hardy's treatment of death and remembrance.

Conclusion

"Ah, Are You Digging On My Grave?" stands as a masterful example of Hardy's poetic craft. Through its dialogue structure, careful use of irony, and progressive revelations, the poem delivers a powerful meditation on death, memory, and the nature of human relationships.

Hardy's poem challenges comfortable assumptions about the lasting nature of human connections and the importance we assume we hold in others' lives. By systematically stripping away the speaker's illusions, Hardy forces readers to confront uncomfortable truths about mortality and the transience of human emotions.

Yet, despite its bleak outlook, the poem's enduring popularity suggests that it resonates with a fundamental human concern about legacy and remembrance. In confronting these uncomfortable truths, Hardy's poem paradoxically ensures its own lasting impact, encouraging readers across generations to grapple with these universal themes.

In its brevity and seeming simplicity, "Ah, Are You Digging On My Grave?" demonstrates Hardy's ability to distill complex philosophical and emotional concepts into accessible, yet profoundly affecting poetry. It stands as a testament to his skill as a poet and his insight into the human condition, cementing his place as one of the most significant literary figures of his era.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!