It was not Death, for I stood up

Emily Dickinson

1830 to 1886

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

It was not Death, for I stood up,

And all the Dead, lie down -

It was not Night, for all the Bells

Put out their Tongues, for Noon.

It was not Frost, for on my Flesh

I felt Siroccos - crawl -

Nor Fire - for just my marble feet

Could keep a Chancel, cool -

And yet, it tasted, like them all,

The Figures I have seen

Set orderly, for Burial

Reminded me, of mine -

As if my life were shaven,

And fitted to a frame,

And could not breathe without a key,

And ’twas like Midnight, some -

When everything that ticked - has stopped -

And space stares - all around -

Or Grisly frosts - first Autumn morns,

Repeal the Beating Ground -

But most, like Chaos - Stopless - cool -

Without a Chance, or spar -

Or even a Report of Land -

To justify - Despair.

Emily Dickinson's It was not Death, for I stood up

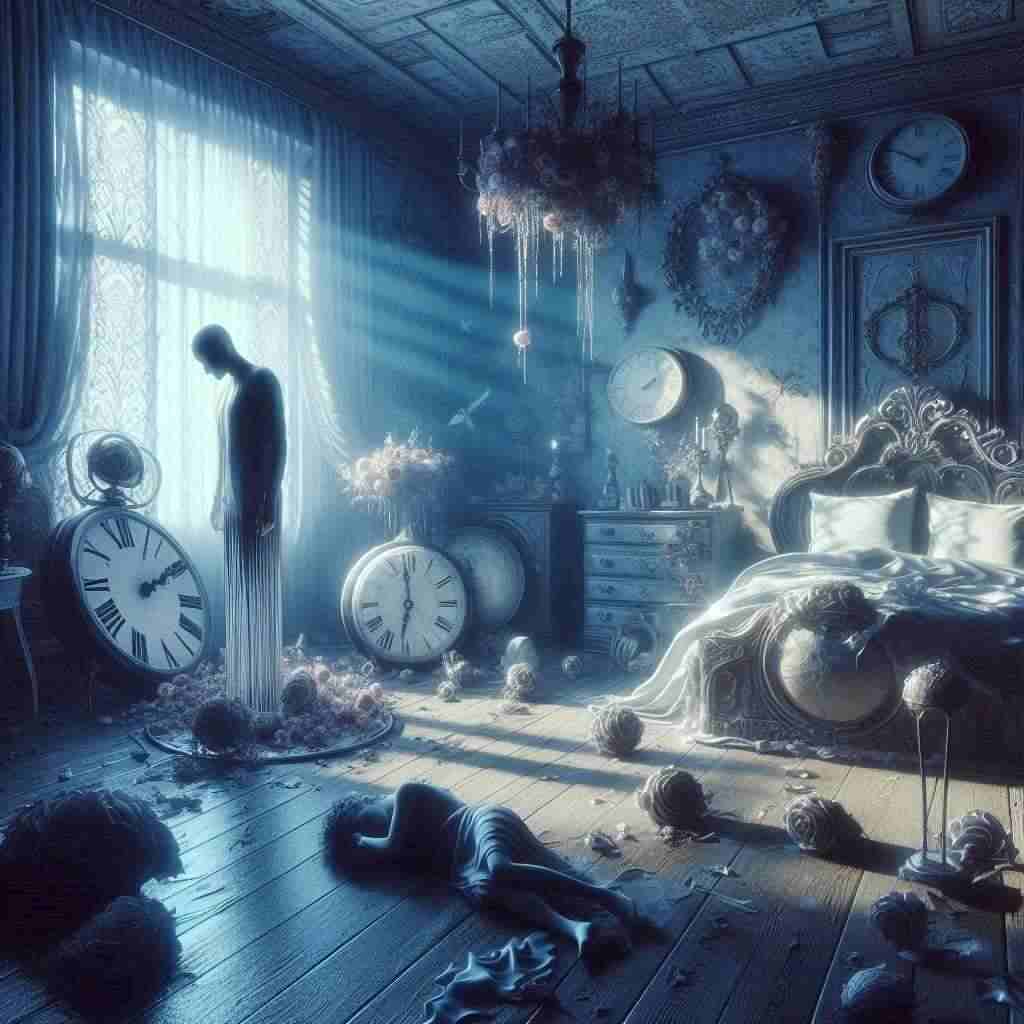

Emily Dickinson's poem "It was not Death, for I stood up" presents a masterful exploration of an ineffable existential experience through a series of negations. This analysis will delve into the poem's intricate use of language, imagery, and structure to convey a profound psychological state that defies simple categorization. We will examine how Dickinson employs various poetic devices to create a tension between the tangible and the intangible, the known and the unknowable, ultimately leading the reader through a labyrinth of consciousness that mirrors the speaker's own disorientation.

The Power of Negation

The poem's opening line, "It was not Death, for I stood up," immediately establishes the central conceit of the work: the definition of an experience through what it is not. This negative definition continues throughout the first half of the poem, with each stanza beginning with a denial: "It was not Night," "It was not Frost," "Nor Fire." This technique serves multiple purposes:

- It creates a sense of mystery and intrigue, compelling the reader to question what this experience could be if it is none of these familiar phenomena.

- It paradoxically defines the experience by accumulating a list of what it is not, gradually narrowing the possibilities and hinting at its true nature.

- It reflects the speaker's own confusion and inability to directly name or describe their state, mirroring the often ineffable nature of profound psychological experiences.

The use of negation also serves to highlight the liminal nature of the speaker's experience. By existing in a space between these defined states (Death, Night, Frost, Fire), the speaker inhabits a realm of in-betweenness that defies easy categorization. This liminality is a key theme in Dickinson's work, often used to explore states of consciousness that exist at the boundaries of human experience.

Imagery and Sensory Experience

Despite the poem's reliance on negation, Dickinson employs vivid imagery and sensory details to give shape to the speaker's experience. The juxtaposition of these concrete images with the abstract nature of the experience creates a tension that runs throughout the poem:

- "all the Bells / Put out their Tongues, for Noon" presents a surreal, almost grotesque image that suggests a distortion of normal perception.

- "on my Flesh / I felt Siroccos - crawl -" introduces a tactile sensation that is both specific (the hot, dusty Sirocco wind) and unsettling in its creeping motion.

- "my marble feet / Could keep a Chancel, cool" combines the coldness of stone with the sanctity of a church, hinting at a state of death-like stillness or preservation.

These images, while vivid, are also deeply contradictory. The noon-time bells conflict with the night-like atmosphere, the hot wind contrasts with the cool marble, and the ability to stand contradicts the death-like state. This use of contradictory imagery reinforces the speaker's sense of disorientation and the uncanny nature of their experience.

Structure and Rhythm

The poem's structure plays a crucial role in conveying the speaker's psychological state. The use of Dickinson's characteristic em-dashes creates pauses and breaks in the flow of the lines, mirroring the fragmented nature of the speaker's thoughts. The irregular rhythm, with its mix of iambic and trochaic feet, further contributes to a sense of unease and instability.

The poem can be divided into two distinct parts:

- The first three stanzas, which focus on negation and concrete imagery.

- The final three stanzas, which shift towards more abstract and cosmic imagery.

This structure mirrors the speaker's psychological journey from attempting to define their experience through familiar concepts to ultimately confronting the ineffable and chaotic nature of their state.

The Turn: "And yet, it tasted, like them all"

The fourth stanza marks a crucial turn in the poem. After establishing what the experience is not, Dickinson writes, "And yet, it tasted, like them all." This line is pivotal for several reasons:

- It introduces a new sensory element - taste - which is often associated with the most intimate and immediate of experiences.

- It contradicts the previous negations, suggesting that the experience somehow encompasses all of the denied states.

- It shifts the poem from pure negation to a more complex, paradoxical understanding of the experience.

This turn reflects a deepening of the speaker's insight into their state. The initial attempts at definition through negation give way to a more nuanced, if still mysterious, comprehension.

Existential Themes and Cosmic Imagery

As the poem progresses, the imagery becomes increasingly abstract and cosmic in scale. The speaker moves from concrete sensations to more existential concerns:

- "As if my life were shaven, / And fitted to a frame" suggests a loss of agency and individuality, as if the speaker's existence has been forcibly constrained.

- "And could not breathe without a key" implies a state of desperate dependence and lack of autonomy.

- "When everything that ticked - has stopped - / And space stares - all around -" evokes a sense of timelessness and infinite void, reminiscent of existential philosophy's concept of the absurd.

The final stanza's imagery of "Chaos - Stopless - cool -" and the absence of even "a Report of Land" pushes this cosmic scale to its limit. The speaker's experience has expanded from a personal, sensory level to encompass a vision of universal disorder and meaninglessness.

The Culmination: Despair and Its Justification

The poem concludes with a striking final line: "To justify - Despair." This ending serves multiple functions:

- It finally names an emotion - despair - that seems to encompass or result from the previously described experience.

- It introduces the concept of justification, suggesting a need to rationalize or make sense of this emotional state.

- It implies that all the preceding imagery and experiences serve as a kind of evidence or justification for this ultimate feeling of despair.

The use of "justify" is particularly interesting, as it suggests a logical or rational approach to understanding an deeply irrational and emotional state. This tension between the desire for understanding and the inherent incomprehensibility of the experience forms the core conflict of the poem.

Conclusion: The Poetics of Existential Crisis

"It was not Death, for I stood up" stands as a tour de force of Dickinson's ability to convey complex psychological states through poetry. Through its use of negation, vivid imagery, and structural innovations, the poem takes the reader on a journey from confusion to a kind of negative enlightenment. The experience described defies easy categorization, much like the existential crises that often accompany profound moments of psychological or spiritual awakening.

Dickinson's poem can be read as an exploration of various states of consciousness: depression, anxiety, depersonalization, or even mystical experience. By refusing to name the state directly and instead circling around it through negation and paradox, Dickinson creates a work that resonates with a wide range of human experiences of alienation and existential doubt.

Ultimately, "It was not Death, for I stood up" demonstrates the power of poetry to articulate the ineffable. Through its careful accumulation of images, sensations, and abstractions, the poem creates a linguistic space that mirrors the psychological state it describes. In doing so, it offers readers not just a description of an existential crisis, but an experience of one, leaving us, like the speaker, grasping for meaning in the face of chaos and despair.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more