Proof

Emily Dickinson

1830 to 1886

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

That I did always love,

I bring thee proof:

That till I loved

I did not love enough.

That I shall love alway,

I offer thee

That love is life,

And life hath immortality.

This, dost thou doubt, sweet?

Then have I

Nothing to show

But Calvary.

Emily Dickinson's Proof

Love, Immortality, and the Shadow of Calvary

Emily Dickinson’s poetry is renowned for its compression of vast emotional and philosophical depth into deceptively simple verse. "Proof," a brief but potent poem, encapsulates her preoccupation with love, mortality, and transcendence. Through its layered assertions and stark concluding image, the poem moves from a declaration of love’s sufficiency to an almost startling evocation of suffering as the ultimate testament. This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its literary devices, thematic concerns, and emotional impact, while also considering Dickinson’s biographical and philosophical influences.

Historical and Cultural Context

Dickinson wrote during the mid-19th century, a period marked by the rise of Romanticism and Transcendentalism in American literature. These movements emphasized emotion, individualism, and a spiritual connection with the divine, often bypassing institutional religion in favor of personal revelation. Dickinson, though deeply influenced by these ideas, also resisted them, crafting a poetic voice that was both mystical and skeptical.

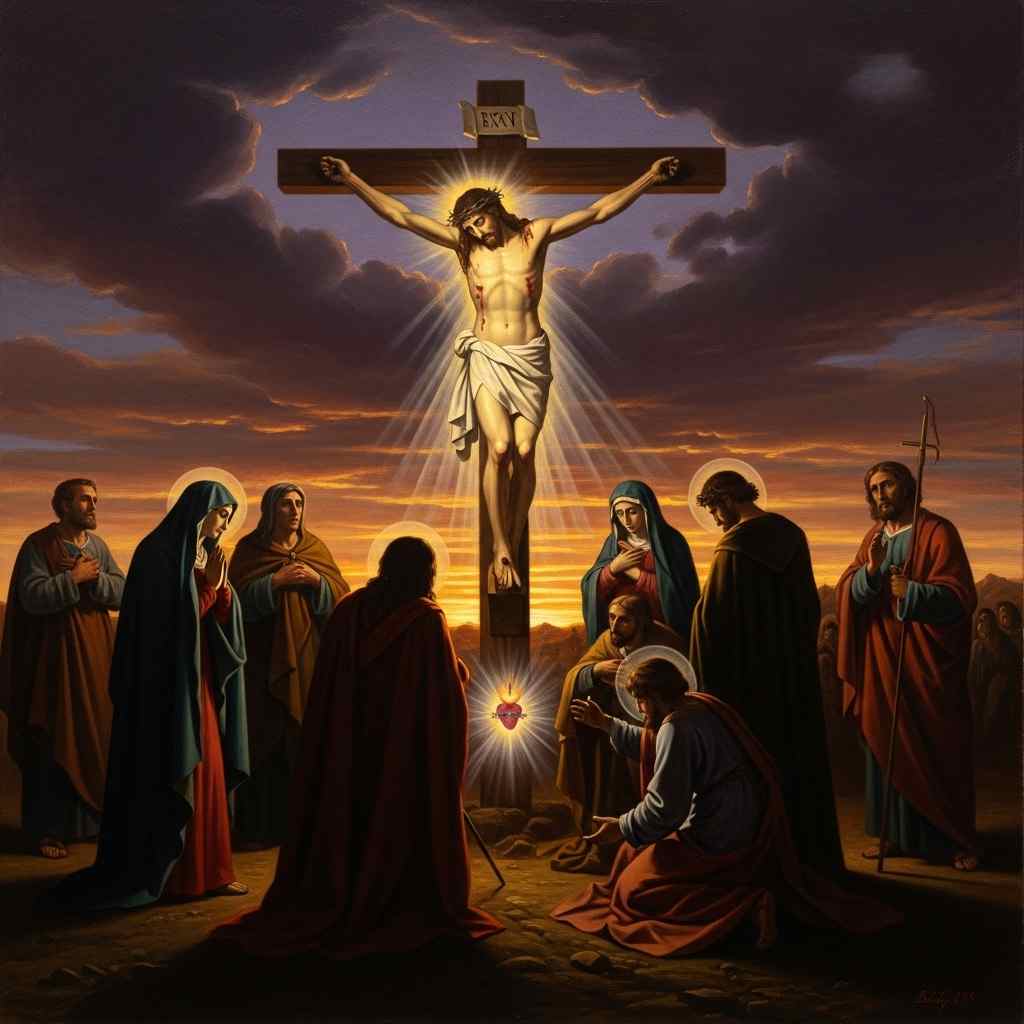

The poem’s reference to "Calvary" (the site of Christ’s crucifixion) situates it within a Christian framework, yet Dickinson’s treatment of religious imagery is unconventional. Rather than affirming orthodox faith, she often employs biblical allusions to explore doubt, suffering, and the limits of human understanding. In "Proof," the speaker’s invocation of Calvary is not a straightforward affirmation of religious belief but rather a startling, almost defiant gesture—suggesting that if love cannot be believed, then only suffering remains as evidence.

Additionally, Dickinson’s reclusive lifestyle and intense inner world shaped her poetry. Her relationships—particularly her mysterious, possibly unrequited loves—fueled many of her verses. While scholars debate the identities of her addressees (whether real or imagined), the emotional urgency in "Proof" suggests a deeply personal investment in its argument.

Literary Devices and Structure

Despite its brevity, "Proof" is rich in literary techniques that amplify its meaning:

1. Paradox and Logical Argumentation

The poem begins with a paradoxical assertion: "That I did always love, / I bring thee proof: / That till I loved / I did not love enough." The speaker claims to have always loved, yet simultaneously admits that before loving fully, their love was insufficient. This paradox mirrors the Romantic notion that love is both an eternal truth and an evolving experience. The phrasing resembles a logical proof, as if the speaker is constructing an irrefutable argument—yet the "proof" is not empirical but emotional and metaphysical.

2. Metaphor and Symbolism

The central metaphor—"love is life, / And life hath immortality"—equates love with existence itself, suggesting that to love is to partake in something eternal. This idea resonates with Transcendentalist thought, particularly Emerson’s belief in the soul’s immortality. However, Dickinson’s treatment is more ambiguous; she does not offer easy consolation. The abrupt shift to "Calvary" in the final lines introduces a symbol of suffering and sacrifice, complicating the earlier assertion of love’s transcendence.

3. Diction and Tone

The poem’s tone shifts from confident declaration to vulnerability. The opening lines are assertive, even legalistic ("I bring thee proof"), but the final stanza introduces doubt: "This, dost thou doubt, sweet? / Then have I / Nothing to show / But Calvary." The word "sweet" softens the address, yet the offering of "Calvary" as the only remaining evidence is jarring. The choice of "show" instead of "prove" is significant—proof has failed, and all that remains is a spectacle of suffering.

Themes

1. Love as Absolute and Ineffable

The poem posits love as both a measurable truth ("proof") and an ineffable force beyond quantification. The speaker insists that their love was always present, yet only fully realized in its current form—a sentiment reminiscent of Plato’s Symposium, where love is a progression toward higher understanding. The assertion that "love is life, / And life hath immortality" suggests that love transcends individual existence, aligning with Dickinson’s frequent exploration of eternity.

2. Doubt and the Limits of Proof

The poem’s central tension lies in the fragility of its own argument. The speaker offers love as proof, yet acknowledges that the beloved might doubt. In response, the only remaining evidence is "Calvary"—a symbol of extreme suffering. This implies that if love cannot be believed, the only alternative is pain, perhaps suggesting that suffering is the one undeniable human experience.

3. Suffering as the Ultimate Testimony

The reference to Calvary is striking because it replaces abstract declarations of love with an image of agony. In Christian theology, Christ’s crucifixion is both a sacrifice and a proof of divine love. Dickinson’s use of the image, however, feels more desperate—as if the speaker is saying, "If you won’t believe my love, then all that’s left is my suffering." This aligns with her broader poetic preoccupation with pain as a form of truth.

Comparative Analysis

Dickinson’s treatment of love and suffering invites comparison with other poets:

-

John Donne: Like Donne in "Batter my heart, three-person'd God," Dickinson employs religious imagery to express personal anguish. However, Donne’s poems often resolve in spiritual surrender, whereas Dickinson’s "Proof" ends on a note of unresolved tension.

-

Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese also grapple with love’s proof, but her conclusions are more assured. Dickinson’s poem, by contrast, leaves the argument unsettled, with suffering as the final, ambiguous evidence.

-

Walt Whitman: Whitman’s expansive declarations of love in "Song of Myself" contrast with Dickinson’s compressed, almost claustrophobic intensity. Where Whitman celebrates love as a unifying force, Dickinson presents it as a fraught, possibly unverifiable truth.

Philosophical and Biographical Insights

Dickinson’s letters reveal a mind deeply engaged with questions of faith, love, and mortality. Her famous line, "My life had stood—a Loaded Gun—" similarly juxtaposes power and vulnerability, much like "Proof" moves from assertion to desperation. Some scholars speculate that her seclusion intensified her focus on internal struggles, making her poetry a battleground for existential questions.

Philosophically, the poem resonates with Søren Kierkegaard’s idea of the "leap of faith"—the notion that belief cannot be rationally proven but must be embraced despite doubt. The speaker’s shift from logical proof to the starkness of Calvary mirrors this existential pivot.

Emotional Impact

The poem’s power lies in its abrupt tonal shift. The initial confidence—"That I did always love"—gives way to a startling vulnerability. The final image of Calvary is emotionally devastating, suggesting that love, when doubted, collapses into pure suffering. This resonates with anyone who has struggled to articulate or validate their deepest emotions.

Conclusion

"Proof" is a masterful distillation of Dickinson’s poetic genius—compact yet expansive, logical yet deeply emotional. It moves from the abstract to the visceral, from love’s idealism to the stark reality of suffering. In doing so, it captures the human struggle to prove the unprovable: the depth of one’s own heart. The poem leaves us with an unsettling truth—that when words fail, only sacrifice remains as testament. In this, Dickinson achieves what few poets can: she makes the ineffable palpable, and the personal universal.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!