The Lost Thought

Emily Dickinson

1830 to 1886

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

I felt a clearing in my mind

As if my brain had split;

I tried to match it, seam by seam,

But could not make them fit.

The thought behind I strove to join

Unto the thought before,

But sequence ravelled out of reach

Like balls upon a floor.

Emily Dickinson's The Lost Thought

Emily Dickinson’s The Lost Thought is a compact yet profound meditation on the fragility of cognition, the elusiveness of memory, and the inherent instability of human thought. Composed in her signature elliptical style, the poem captures a moment of mental rupture—a sudden, jarring discontinuity in the speaker’s consciousness. Through vivid imagery and deft use of metaphor, Dickinson explores the anxiety of intellectual and emotional dislocation, a theme that resonates deeply within her broader oeuvre. This essay will examine the poem’s historical and cultural context, its literary devices, central themes, and emotional impact, while also considering Dickinson’s biographical preoccupations and philosophical undertones.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate The Lost Thought, one must situate it within the intellectual climate of mid-19th-century America, a period marked by rapid scientific advancement, religious skepticism, and growing interest in the workings of the human mind. The rise of psychological studies, influenced by early neurologists and philosophers such as William James, brought new attention to the mechanics of cognition. Dickinson, though reclusive, was deeply engaged with contemporary thought, reading widely in theology, botany, and metaphysics. Her poetry often grapples with the tension between empirical observation and ineffable experience, a tension palpable in The Lost Thought.

Additionally, the poem reflects the Romantic and Transcendentalist fascination with the instability of perception. Writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe explored the limits of human understanding, often portraying the mind as both a vessel of sublime insight and a site of terrifying fragmentation. Dickinson’s depiction of a thought unraveling “like balls upon a floor” echoes Poe’s The Imp of the Perverse (1845), in which the narrator describes the mind’s tendency toward self-sabotage and irrational slippage. Yet where Poe’s work leans toward the Gothic, Dickinson’s treatment is more introspective, even clinical in its precision.

Literary Devices and Structure

Despite its brevity, The Lost Thought is rich in literary techniques that amplify its psychological intensity. Dickinson employs metaphor, enjambment, and stark imagery to convey the speaker’s mental disarray.

1. Metaphor and Simile

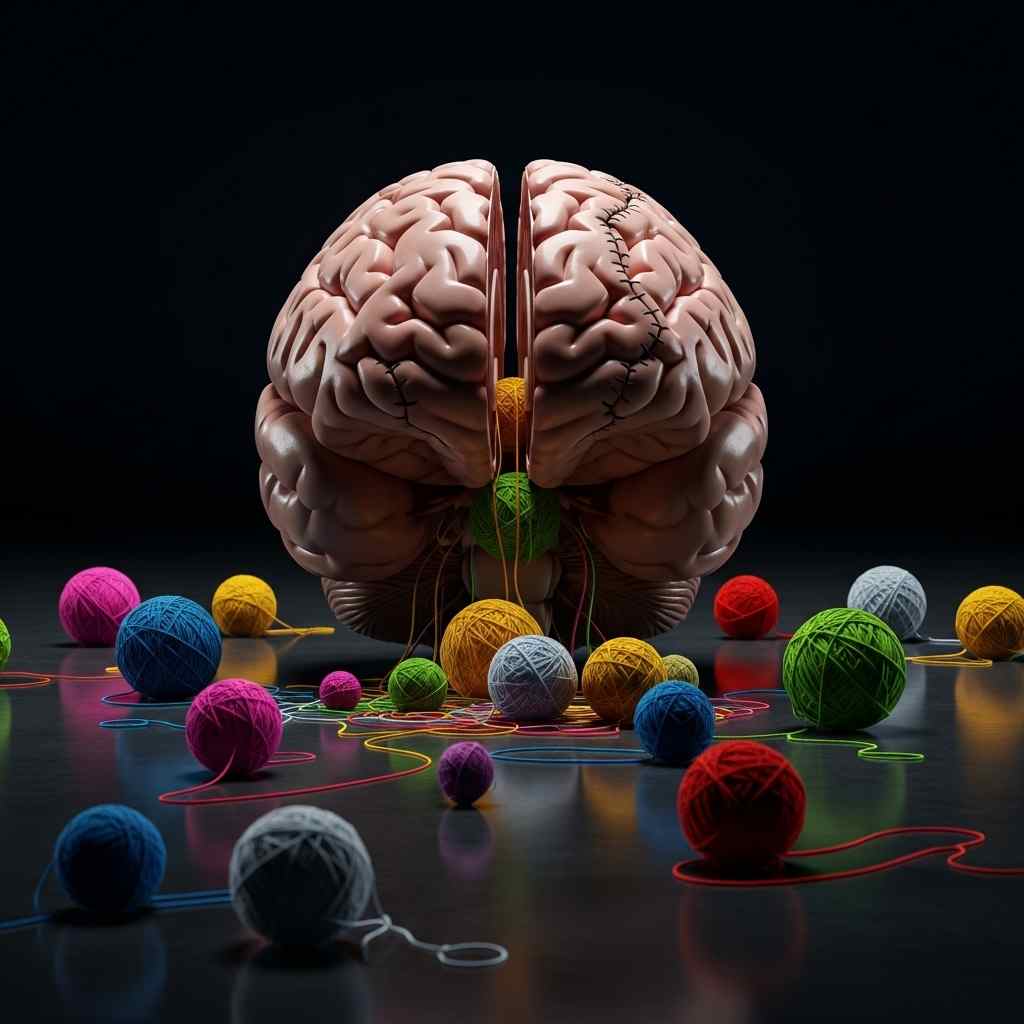

The poem hinges on two central metaphors: the mind as a fractured object (“my brain had split”) and thought as a tangible, yet uncontrollable, substance (“Like balls upon a floor”). The first metaphor suggests a violent rupture, as though the mind has been physically sundered. This aligns with Dickinson’s frequent use of bodily imagery to depict psychological states—her poems often describe emotions in terms of wounds, fractures, or physical weights.

The simile in the final lines is particularly striking: sequence “ravelled out of reach / Like balls upon a floor.” The image of scattered balls implies both childlike play and frustrating chaos. There is a sense of futility in the speaker’s attempt to gather what has been lost, evoking the Sisyphean struggle to reconstruct meaning once coherence has dissolved.

2. Enjambment and Syntax

Dickinson’s use of enjambment mirrors the disjointedness of the speaker’s thoughts. The line “I tried to match it, seam by seam,” spills into the next without resolution, enacting the very failure it describes. The poem’s syntax, too, reinforces its theme: the abrupt breaks between clauses (“But could not make them fit”) mimic the stuttering motion of a mind grasping for continuity.

3. Paradox and Irony

The poem’s opening contains a subtle paradox: “a clearing in my mind” suggests both illumination and emptiness. A “clearing” might imply newfound clarity, yet here it denotes a disturbing vacancy. This irony is quintessentially Dickinsonian—her work frequently juxtaposes opposing states (certainty/doubt, presence/absence) to underscore the instability of perception.

Themes

1. The Fragility of Thought

At its core, The Lost Thought is about the precarious nature of cognition. The speaker experiences a mental lapse so severe it feels like a physical rupture. This aligns with Dickinson’s broader preoccupation with the limits of language and understanding. Many of her poems (I felt a Funeral, in my Brain, The Brain—is wider than the Sky—) explore the mind’s vastness alongside its vulnerability. Here, the “lost thought” becomes emblematic of the ephemerality of human reason—what is grasped one moment may vanish the next.

2. The Failure of Reconstruction

The speaker’s attempt to “match” the fractured thoughts “seam by seam” evokes the labor of stitching a torn fabric. Yet the effort is futile; the sequence “ravel[s] out of reach.” This imagery suggests that some fractures in understanding cannot be mended, a theme Dickinson revisits in poems like After great pain, a formal feeling comes—, where trauma leaves the self irreparably altered. The inability to reconstruct the thought speaks to a deeper existential anxiety—the fear that coherence itself is illusory.

3. The Uncanny in Mental Processes

There is something unsettling about the poem’s depiction of a mind turning against itself. The brain’s “split” is not willed but experienced passively, as though the speaker is a spectator to her own disintegration. This aligns with Freud’s later concept of the uncanny—the familiar made strange. The mind, usually the seat of control, becomes alien, its processes opaque even to the thinker.

Emotional Impact

Despite its abstract subject, The Lost Thought generates visceral unease. The suddenness of the “clearing” evokes the jolt of a memory lapse or the disorientation of a fever dream. Dickinson’s restrained diction (“I tried to match it”) only heightens the pathos—the speaker’s quiet desperation is more affecting than outright despair.

The poem also captures the loneliness of cognitive failure. Unlike a shared experience, a lost thought is isolating; no one else can retrieve it for the speaker. This solitude is a recurring motif in Dickinson’s work, where consciousness is often a private, incommunicable realm.

Comparative Analysis

Dickinson’s portrayal of mental fragmentation invites comparison with other writers. T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922), with its disjointed imagery and fractured narration, similarly depicts a mind struggling to impose order on chaos. However, where Eliot’s fragmentation reflects cultural collapse, Dickinson’s is deeply personal, an internal rather than societal rupture.

A closer parallel exists with Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape (1958), where the protagonist grapples with the elusiveness of memory. Like Dickinson’s speaker, Krapp attempts to reconstruct the past but finds it slipping away, “ravelled out of reach.” Both works suggest that the act of remembering is inherently unstable.

Biographical and Philosophical Insights

Dickinson’s own life offers possible clues to the poem’s preoccupations. Her letters reveal a mind acutely aware of its own limitations—she frequently describes moments of intellectual and spiritual doubt. Additionally, her near-total reclusion in later years suggests a profound engagement with the solipsistic nature of thought. The Lost Thought may thus be read as an existential meditation: if the self is constituted by its thoughts, what happens when those thoughts dissolve?

Philosophically, the poem resonates with Cartesian dualism—the separation of mind and body—but subverts it. Descartes’ cogito ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”) assumes the continuity of thought as proof of existence. Dickinson’s poem, however, questions this certainty: if thought can fracture, does the self remain intact?

Conclusion

The Lost Thought is a masterful exploration of cognitive fragility, rendered with Dickinson’s characteristic precision and depth. Through metaphor, syntax, and stark imagery, the poem captures the terror and loneliness of mental discontinuity, while also reflecting broader 19th-century anxieties about perception and selfhood. Its emotional resonance lies in its universality—who has not felt the frustration of a thought slipping away? In just eight lines, Dickinson distills an entire epistemology of doubt, reminding us that the mind, for all its brilliance, is never fully within our control.

In the grand tapestry of her work, this poem stands as a testament to her ability to articulate the ineffable—to give form to the fleeting, the fractured, and the lost.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!