The Slave Singing at Midnight

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

1807 to 1882

Loud he sang the psalm of David!

He, a Negro and enslaved,

Sang of Israel's victory,

Sang of Zion, bright and free.

In that hour, when night is calmest,

Sang he from the Hebrew Psalmist,

In a voice so sweet and clear

That I could not choose but hear,

Songs of triumph, and ascriptions,

Such as reached the swart Egyptians,

When upon the Red Sea coast

Perished Pharaoh and his host.

And the voice of his devotion

Filled my soul with strange emotion;

For its tones by turns were glad,

Sweetly solemn, wildly sad.

Paul and Silas, in their prison,

Sang of Christ, the Lord arisen,

And an earthquake's arm of might

Broke their dungeon-gates at night.

But, alas! what holy angel

Brings the Slave this glad evangel?

And what earthquake's arm of might

Breaks his dungeon-gates at night?

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's The Slave Singing at Midnight

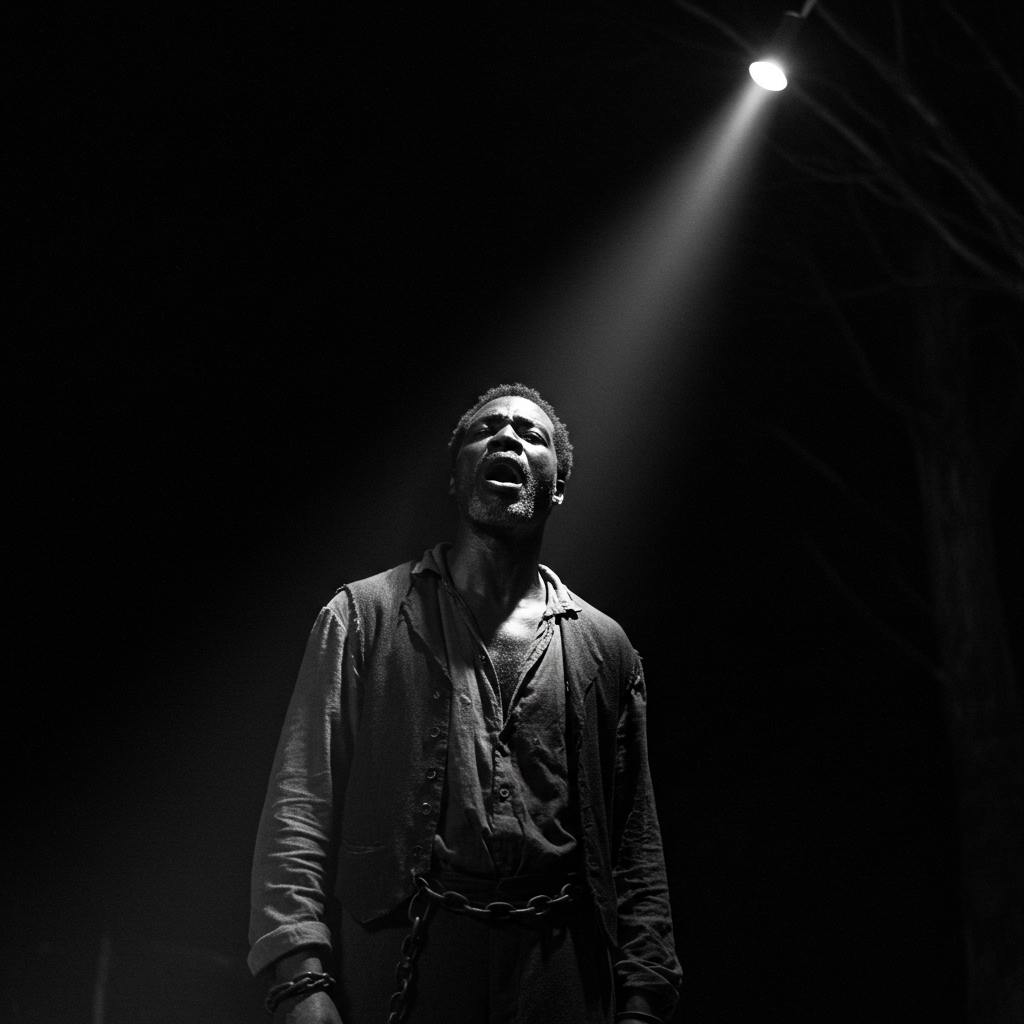

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Slave Singing at Midnight (1842) emerges as a poignant intersection of religious symbolism, abolitionist sentiment, and Romantic introspection. Written during a period of escalating national tension over slavery, the poem transcends its immediate historical context to explore universal themes of spiritual resilience, the paradox of artistic expression under oppression, and the moral contradictions of a Christian society upholding human bondage. By weaving biblical allegory with visceral emotionality, Longfellow crafts a work that resonates as both a specific critique of antebellum America and a timeless meditation on the human capacity for hope amid despair.

Historical and Cultural Context

Longfellow composed the poem as part of his Poems on Slavery (1842), a collection reflecting his growing abolitionist leanings following conversations with Charles Dickens, who had recently documented American slavery’s horrors47. While less politically confrontational than contemporaries like William Lloyd Garrison, Longfellow leverages his status as America’s most beloved poet to humanize enslaved individuals through art. The poem’s focus on a Black man’s voice subverts minstrelsy stereotypes prevalent in 1840s culture, which often depicted enslaved people as jovial or childlike4. Instead, Longfellow centers the slave’s intellectual and spiritual depth-a radical gesture for a white Northern audience largely insulated from slavery’s brutalities.

The poem’s biblical framework-particularly its references to Exodus and the imprisonment of Paul and Silas (Acts 16:25-26)-mirrors the coded resistance found in African American spirituals. As Kathryn Bauer notes, enslaved communities often reinterpreted Scripture to affirm their humanity and envision liberation4. Longfellow’s slave sings not merely for solace but to assert an unbreakable connection to divine justice, transforming the psalm into a “weapon of the weak”3. This aligns with Frederick Douglass’s contemporaneous writings, which describe songs as expressions of “unutterable sorrow” and covert protest4.

Literary Devices and Symbolic Structure

Longfellow employs layered contrasts to heighten the poem’s emotional tension:

1. Auditory vs. Visual Imagery

The slave remains physically absent, his presence conjured solely through sound-“a voice so sweet and clear / That I could not choose but hear”1. This ethereal vocalization contrasts with the implied darkness of his cell, creating a dialectic between the invisibility enforced by slavery and the irreducible humanity proclaimed through song. The poet’s emphasis on hearing over seeing mirrors the clandestine nature of slave spirituality, which often flourished beyond masters’ surveillance3.

2. Biblical Allusion as Subversive Parallel

The poem’s central metaphor equates the slave with biblical figures who transcend captivity through faith. By singing of “Israel’s victory” and “Zion, bright and free,” the enslaved man aligns himself with the Hebrews escaping Egyptian bondage-a direct challenge to pro-slavery theology that justified oppression via the Curse of Ham14. Similarly, the reference to Paul and Silas (whose prayers triggered a liberating earthquake) underscores the bitter irony of the slave’s unanswered cries: “what holy angel / Brings the Slave this glad evangel?”17. Longfellow here critiques a nation that venerates Scripture while denying its most vulnerable citizens the freedom it celebrates.

3. Emotional Dissonance

The shifting tones of the slave’s voice-“by turns were glad, / Sweetly solemn, wildly sad”-mirror the psychological complexity of survival under slavery13. This “strange emotion” experienced by the listener reflects white America’s uneasy conscience: admiration for the slave’s artistry alongside complicity in his suffering4. The poem’s unresolved ending (“what earthquake’s arm of might / Breaks his dungeon-gates at night?”) leaves this tension raw, rejecting facile redemption narratives1.

Thematic Explorations

Faith as Dual-Edged Sword

The slave’s devotion exemplifies what W.E.B. Du Bois later termed “double-consciousness”: his faith sustains dignity yet also embodies the internalized oppression of a Christian ideology manipulated to justify slavery34. Longfellow, however, complicates this by highlighting the subversive potential of religious metaphor. When the slave sings of Pharaoh’s defeat, he reclaims Scripture as a tool of resistance, transforming psalms into “songs of triumph” that prophesy his own liberation17.

The Paradox of Artistic Expression

Music here functions as both catharsis and defiance. The slave’s midnight singing-a time when “night is calmest”-suggests creativity flourishing in moments of enforced stillness1. Yet his voice also pierces the darkness, a sonic rebellion against spatial and social confinement. This aligns with Romantic ideals of art transcending material circumstances, yet Longfellow avoids romanticization by acknowledging the song’s roots in trauma: its beauty is inseparable from the “wildly sad” undercurrent of despair37.

The Spectator’s Complicity

The white narrator’s passive listening-“could not choose but hear”-mirrors Northern abolitionists’ fraught relationship to slavery: bearing witness without fully confronting systemic complicity4. The poem’s power derives from its refusal to resolve this tension, leaving readers unsettled by the disconnect between aesthetic appreciation and moral action.

Biographical and Philosophical Dimensions

Longfellow’s portrayal of the slave’s interiority gains nuance when contrasted with his earlier work. Having translated Dante’s Divine Comedy-a meditation on divine justice-he positions the slave as a modern-day pilgrim navigating an American inferno26. The poem’s focus on vocal resilience also echoes Longfellow’s belief in poetry’s civic role, articulated in his 1832 commencement address advocating for a national literature5.

Yet the poem’s limitations as a white-authored text are evident. Unlike Harriet Beecher Stowe or Frederick Douglass, Longfellow cannot fully inhabit the slave’s perspective, resulting in a portrayal that privileges spiritual transcendence over bodily suffering47. This reflects broader abolitionist tendencies to frame slavery as a moral rather than economic issue, sidestepping the visceral realities of labor exploitation.

Emotional Impact and Legacy

The poem’s enduring resonance lies in its unflinching portrayal of hope’s fragility. The slave’s voice-simultaneously triumphant and anguished-embodies what philosopher Jonathan Lear terms “radical hope”: a commitment to flourishing despite the collapse of familiar ethical frameworks3. By concluding without resolution, Longfellow forces readers to sit with discomfort, resisting the Victorian era’s preference for tidy moral lessons.

Modern readers might critique the poem’s paternalism, yet its emotional honesty retains power. The slave’s song, like the blues tradition it prefigures, transforms personal grief into collective catharsis. In an era where systemic oppression persists through subtler mechanisms, Longfellow’s work reminds us that art remains both a mirror of societal failings and a hammer to shape new realities.

Citations:

- https://poemanalysis.com/henry-wadsworth-longfellow/the-slave-singing-at-midnight/

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Henry-Wadsworth-Longfellow

- https://www.eliteskills.com/c/390

- https://americanstudiesmediacultureprogram.wordpress.com/2017/11/07/longfellows-the-slave-singing-at-midnight-a-white-mans-depiction-of-the-enslaved-in-1842/

- https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/henry-wadsworth-longfellow

- https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/henry-wadsworth-longfellow

- https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/the-slave-singing-at-midnight

- https://pages.stolaf.edu/americanmusic/2018/04/30/abolition-music-and-the-imagined-slave/

- https://www.nps.gov/long/learn/historyculture/longfellows-poems-on-slavery.htm

- https://theamericanscholar.org/how-longfellow-woke-the-dead/

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/2916887

- https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/the-slave-singing-at-midnight

- https://www.hwlongfellow.org/poems_poem.php?pid=78

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/beyond-poems-on-slavery.htm

- https://www.bccollegeasansol.ac.in/download.php?id=89

- https://pages.stolaf.edu/americanmusic/tag/abolitionist-music/

- https://poets.org/poet/henry-wadsworth-longfellow

- https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Wadsworth_Longfellow

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poems_on_Slavery

- https://www.nps.gov/long/learn/historyculture/longfellow-and-abolition.htm

- https://www.nps.gov/long/learn/education/upload/Longfellow-s-Life-Legacy.pdf

- https://www.123helpme.com/essay/The-Slave-Singing-At-Midnight-Essay-9A357B7294DB9EC4

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/rethinking-literary-form-gender-roles-slave-narratives-sakshi-arya

- https://www.biblestudytools.com/bible-study/topical-studies/theology-at-midnight-11637085.html

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/african-american-literature-in-transition-18501865/black-romanticism-and-the-lyric-as-the-medium-of-the-conspiracy/EE0332247859D01A02C4AFE26B3A271A

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more