Twilight

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

1807 to 1882

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

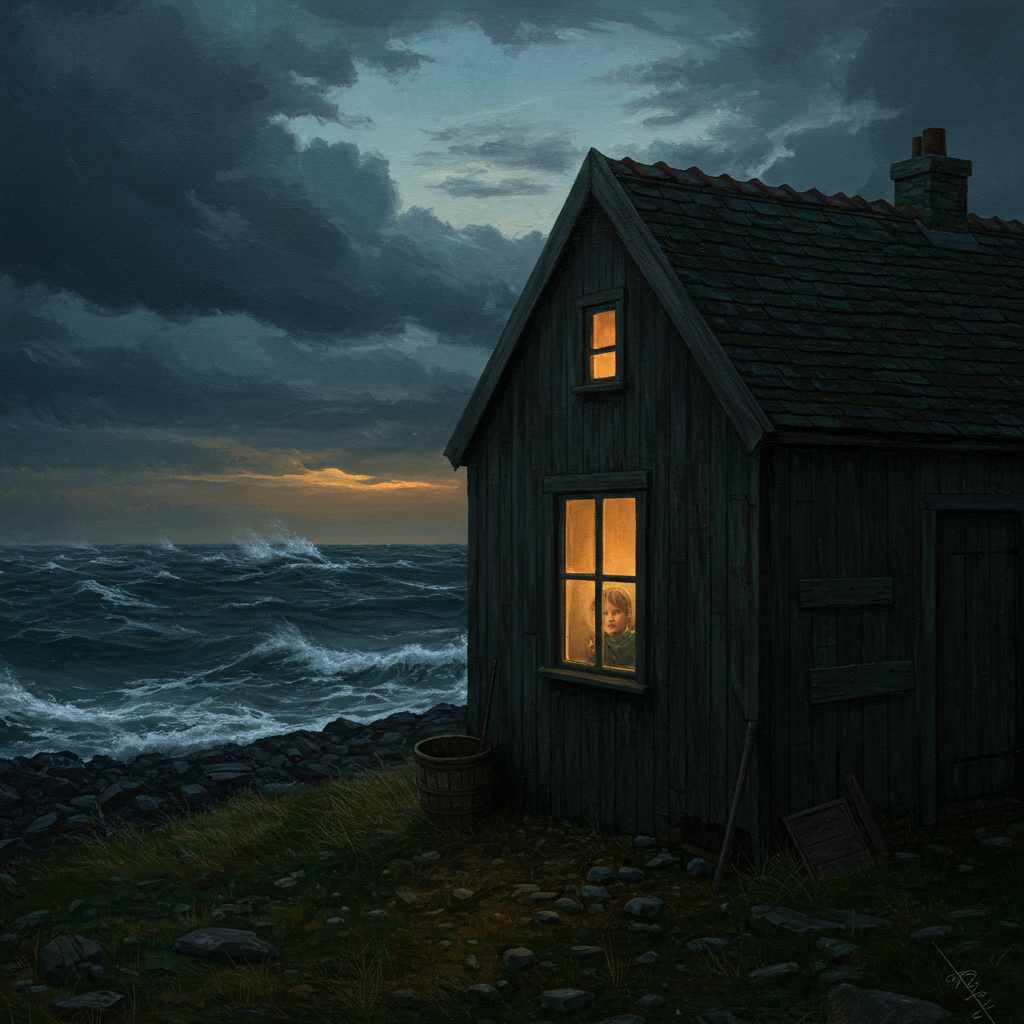

The twilight is sad and cloudy,

The wind blows wild and free,

And like the wings of sea-birds

Flash the white caps of the sea.

But in the fisherman's cottage

There shines a ruddier light,

And a little face at the window

Peers out into the night.

Close, close it is pressed to the window,

As if those childish eyes

Were looking into the darkness,

To see some form arise.

And a woman's waving shadow

Is passing to and fro,

Now rising to the ceiling,

Now bowing and bending low.

What tale do the roaring ocean,

And the night-wind, bleak and wild,

As they beat at the crazy casement,

Tell to that little child?

And why do the roaring ocean,

And the night-wind, wild and bleak,

As they beat at the heart of the mother,

Drive the color from her cheek?

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's Twilight

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Twilight is a brief yet evocative poem that captures the interplay between nature’s tempestuousness and human vulnerability. Through vivid imagery and subtle emotional tension, Longfellow constructs a scene that is both intimate and universal, exploring themes of anticipation, fear, and the protective instincts of family. This essay will examine the poem’s historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its thematic concerns, and its emotional resonance, while also considering Longfellow’s broader poetic philosophy.

Historical and Cultural Context

Longfellow, a central figure in 19th-century American literature, was deeply influenced by Romanticism, which emphasized emotion, nature, and individualism. Twilight reflects these Romantic sensibilities, particularly in its juxtaposition of the sublime power of nature with the fragile domestic sphere. The poem’s setting—a fisherman’s cottage by a stormy sea—evokes the perilous lives of coastal communities, where the ocean was both a source of sustenance and a constant threat.

During Longfellow’s lifetime (1807–1882), maritime industries were vital to New England’s economy, yet they carried inherent dangers. Shipwrecks and drownings were common, and the anxiety of families awaiting the return of fishermen was a recurring motif in literature of the period. Longfellow, who spent much of his life in coastal Massachusetts, would have been acutely aware of these realities. His poem The Wreck of the Hesperus similarly grapples with the ocean’s destructive force, suggesting a preoccupation with the tension between human endurance and natural indifference.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Longfellow’s mastery of imagery is evident in Twilight. The poem opens with a melancholic and turbulent natural scene:

The twilight is sad and cloudy,

The wind blows wild and free,

And like the wings of sea-birds

Flash the white caps of the sea.

The personification of twilight as "sad" immediately establishes an emotional tone, while the simile comparing white-capped waves to "the wings of sea-birds" introduces a fleeting, almost spectral quality. The ocean is not merely a backdrop but an active, almost sentient force, its movement mirroring the unrest within the cottage.

Inside, the "ruddier light" of the fisherman’s home contrasts with the bleak outdoors, symbolizing warmth and human resilience. The "little face at the window" becomes a focal point, embodying innocence and apprehension. The child’s gaze into the darkness suggests both curiosity and dread—perhaps awaiting a father’s return or fearing his loss.

The woman’s "waving shadow" is another striking image, its restless motion ("rising to the ceiling, / Now bowing and bending low") reflecting her anxiety. Unlike the child, who peers outward, the mother is caught in a repetitive, almost ritualistic movement, as if her actions could will safety upon the absent fisherman.

Themes: Nature’s Indifference and Human Vulnerability

A central theme in Twilight is the contrast between nature’s relentless power and human fragility. The ocean and wind are depicted as wild, chaotic forces—"roaring," "bleak," and "wild"—while the cottage, though a sanctuary, is fragile ("the crazy casement"). The storm does not merely rage outside; it intrudes upon the emotional state of the inhabitants, "beat[ing] at the heart of the mother" and draining the color from her cheeks.

This dynamic echoes the Romantic notion of the sublime—nature’s capacity to evoke awe and terror. Unlike the transcendental optimism of Emerson or Whitman, however, Longfellow’s portrayal of nature is ambivalent. It is beautiful in its wildness ("like the wings of sea-birds") yet menacing in its indifference to human suffering.

The poem also explores the psychology of waiting. The child and mother are suspended in a moment of uncertainty, their fear unspoken but palpable. The unanswered questions—

What tale do the roaring ocean,

And the night-wind, bleak and wild,

As they beat at the crazy casement,

Tell to that little child?

—heighten the tension, implying that the storm carries a message too dreadful to articulate. The final stanza shifts focus to the mother, whose pallor suggests she understands the ocean’s language all too well.

Comparative Analysis: Longfellow and the Lure of the Sea

Longfellow’s treatment of the sea aligns with other maritime literature of his time. In Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach, the ocean similarly symbolizes existential uncertainty, while in Emily Dickinson’s I started Early – Took my Dog –, it is a seductive yet dangerous presence. Unlike Arnold’s philosophical despair or Dickinson’s surrealism, however, Longfellow’s approach is narrative and empathetic. His focus on domestic anxiety—rather than abstract meditation—grounds the poem in human experience.

A closer parallel can be drawn with Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s Break, Break, Break, where the sea’s ceaseless motion contrasts with the poet’s grief. Both poems use the ocean as a metaphor for uncontrollable forces, but Longfellow’s emphasis on familial bonds adds a layer of communal sorrow absent in Tennyson’s more personal lament.

Biographical and Philosophical Undercurrents

Longfellow’s life was marked by personal tragedy, including the death of his first wife, Mary, and his second wife, Fanny, in a fire. While Twilight predates these losses, his later works, such as The Cross of Snow, reveal a deepening preoccupation with grief and endurance. The mother’s silent dread in Twilight may thus foreshadow Longfellow’s later explorations of sorrow.

Philosophically, the poem raises questions about fate and agency. The mother and child are passive observers, their fate tied to forces beyond their control. This resignation contrasts with the Romantic ideal of individualism, suggesting Longfellow’s nuanced view of human powerlessness in the face of nature.

Emotional Impact and Conclusion

Twilight derives its emotional power from restraint. Longfellow does not depict the fisherman’s fate; the poem’s tension lies in its unanswered questions. The child’s innocence amplifies the tragedy—what does the storm "tell" them? Does the mother’s fear stem from experience, or is it a primal instinct?

The poem’s brevity enhances its impact. In just a few lines, Longfellow captures a microcosm of human vulnerability, making Twilight a poignant meditation on love, fear, and the indifferent majesty of nature. Its themes remain timeless, resonating with anyone who has waited in uncertainty, listening to the wind and wondering what the night will bring.

Longfellow’s ability to distill profound emotion into simple yet vivid imagery secures Twilight a place among his most affecting works. It is a testament to poetry’s capacity to evoke empathy, to make the reader feel the chill of the wind, the flicker of the fire, and the quiet terror of the unknown.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more