A Valediction: of weeping

John Donne

1572 to 1631

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

Let me powre forth

My teares before thy face, whil'st I stay here,

For thy face coines them, and thy stampe they beare,

And by this Mintage they are something worth,

For thus they bee

Pregnant of thee;

Fruits of much griefe they are, emblemes of more,

When a teare falls, that thou falst which it bore,

So thou and I are nothing then, when on a divers shore.

On a round ball

A workeman that hath copies by, can lay

An Europe, Afrique, and an Asia,

And quickly make that, which was nothing, All,

So doth each teare,

Which thee doth weare,

A globe, yea world by that impression grow,

Till thy teares mixt with mine doe overflow

This world, by waters sent from thee, my heaven dissolved so.

O more then Moone,

Draw not up seas to drowne me in thy spheare,

Weepe me not dead, in thine armes, but forbeare

To teach the sea, what it may doe too soone;

Let not the winde

Example finde,

To doe me more harme, then it purposeth;

Since thou and I sigh one anothers breath,

Who e'r sighes most, is cruellest, and hasts the others death.

John Donne's A Valediction: of weeping

John Donne’s A Valediction: of weeping is a poignant exploration of love, separation, and the profound emotional resonance of tears. Written during the Renaissance, a period marked by both intellectual vigor and deep emotional expressiveness, Donne’s poem exemplifies the metaphysical conceit—a hallmark of his poetic style—whereby abstract emotions are rendered through startlingly concrete imagery. The poem is a valediction, a farewell, but unlike the more famous A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning, this work dwells on the sorrow of parting rather than the spiritual unity that transcends it. Through intricate metaphors of coinage, globes, and celestial influence, Donne transforms weeping into a complex act of creation and destruction, where tears become both a testament to love and a harbinger of dissolution.

This analysis will examine the poem’s structure, imagery, and thematic concerns, situating it within Donne’s broader oeuvre and the cultural milieu of early 17th-century England. Additionally, it will explore how the poem engages with Renaissance ideas of cosmology, alchemy, and the metaphysics of love, revealing Donne’s unique ability to fuse intellectual rigor with raw emotional intensity.

The Alchemy of Tears: Coinage and Creation

The poem opens with an arresting metaphor: the speaker’s tears are coins minted by the beloved’s face.

Let me powre forth

My teares before thy face, whil’st I stay here,

For thy face coines them, and thy stampe they beare…

Here, Donne employs the language of currency to suggest that the beloved’s image gives value to the speaker’s grief. The act of weeping is not passive but generative—tears are “pregnant” with the beloved’s essence, becoming “emblemes of more,” symbols of an impending, greater sorrow. This metaphor extends into a paradox: if tears bear the beloved’s image, then when a tear falls, the beloved falls with it, rendering both lover and beloved “nothing” when separated.

The monetary imagery is significant in a Renaissance context, where alchemical and economic transformations fascinated thinkers. Just as base metals were believed transmutable into gold, Donne’s tears are alchemized by love into something precious, yet their very existence signifies loss. The conceit also hints at the fragility of human connection—like currency, love circulates, but its value is contingent upon presence.

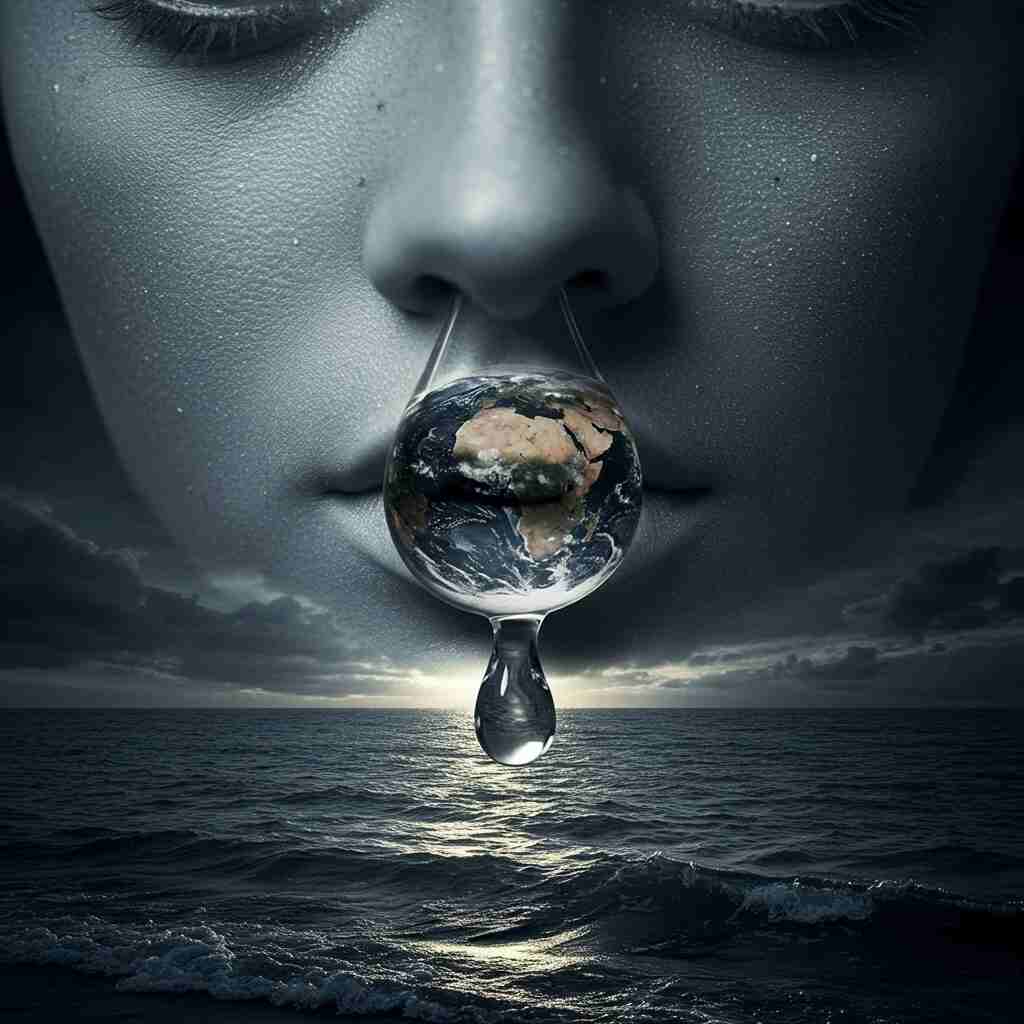

The World in a Tear: Cosmic and Cartographic Imagery

Donne’s metaphysical wit shines in the second stanza, where tears become globes mirroring the world:

On a round ball

A workeman that hath copies by, can lay

An Europe, Afrique, and an Asia…

The comparison of tears to a craftsman’s globe underscores their capacity to encapsulate entire worlds. Each tear, imprinted with the beloved’s image, swells into a microcosm, a “globe, yea world.” This reflects Renaissance cartographic enthusiasm—the period saw an explosion of map-making and global exploration—but Donne subverts it for emotional effect. The lovers’ mingled tears “overflow / This world,” suggesting an apocalyptic dissolution, where sorrow erases boundaries between self and other, love and loss.

The imagery also evokes the Ptolemaic cosmology, where celestial spheres governed earthly affairs. The beloved’s influence is so overpowering that her tears could drown the speaker, just as the moon controls tides:

O more then Moone,

Draw not up seas to drowne me in thy spheare…

Here, the beloved is likened to the moon, a traditional symbol of change and flux, but also of gravitational pull. The speaker pleads for restraint, fearing that her grief will amplify natural forces (wind and sea) to destructive ends. This celestial metaphor reinforces the poem’s tension between creation and annihilation—tears construct worlds but also threaten to dissolve them.

The Paradox of Shared Breath: Love and Mortality

The final stanza introduces another striking conceit: lovers sharing breath.

Since thou and I sigh one anothers breath,

Who e’r sighes most, is cruellest, and hasts the others death.

In Renaissance physiology, sighs were thought to deplete vital spirits, hastening death. Donne literalizes this belief, framing love as both life-giving and lethal. The more one sighs, the more one steals breath from the other—an exquisite paradox where intimacy fuels mortality. This echoes Donne’s preoccupation with death in poems like The Flea and Death Be Not Proud, where love and mortality are inextricably linked.

The plea for restraint—Weepe me not dead—resonates with the poem’s central tension: the desire to express grief while fearing its consequences. Unlike A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning, where love transcends physical separation, this poem lingers on the visceral pain of parting, where tears are both tribute and threat.

Historical and Biographical Context

Donne’s own life informs this poem’s emotional urgency. Written during his early career, possibly before his secret marriage to Anne More in 1601 (which led to his imprisonment and social ruin), the poem reflects the anxieties of forbidden or imperiled love. His later works often celebrate spiritual unity, but A Valediction: of weeping captures the raw vulnerability of lovers facing separation.

The Renaissance context also shapes the poem’s intellectual framework. Neo-Platonic ideas—where love connects the material and divine—permeate Donne’s work, but here, the focus is earthly and immediate. The poem’s tension between creation and destruction mirrors the era’s broader anxieties: the discovery of new worlds destabilized old certainties, just as the Reformation challenged religious unity. Donne’s tears, like the expanding globe, suggest both vast possibility and terrifying dissolution.

Conclusion: The Duality of Weeping

A Valediction: of weeping is a masterful fusion of intellect and emotion, where tears are at once currency, cosmos, and catalyst for ruin. Donne’s metaphysical conceits elevate sorrow into a universal force, intertwining love’s generative power with its capacity for devastation. Unlike his more serene valedictions, this poem does not offer consolation but immerses the reader in the paradox of love—that the very expressions which affirm connection also hasten its undoing.

In this way, Donne captures a fundamental human truth: grief is both an act of preservation and surrender. The tears that bear the beloved’s image keep her close, even as their falling signifies separation. The poem’s brilliance lies in its refusal to resolve this tension, instead allowing sorrow its full, contradictory weight. For modern readers, Donne’s exploration remains profoundly relatable—love’s deepest expressions are often those that acknowledge both its grandeur and its fragility.

Through A Valediction: of weeping, Donne reminds us that poetry, like tears, can encapsulate worlds, rendering the most private grief universal. In doing so, he affirms poetry’s enduring power: to give form to feeling, and to find, in the act of mourning, a strange and terrible beauty.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!