Read history

Edna St. Vincent Millay

1892 to 1950

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

Read history: thus learn how small a space

You may inhabit, nor inhabit long

In crowding Cosmos—in that confined place

Work boldly; build your flimsy barriers strong;

Turn round and round, make warm your nest; among

The other hunting beasts, keep heart and face,—

Not to betray the doomed and splendid race

You are so proud of, to which you belong.

For trouble comes to all of us: the rat

Has courage, in adversity, to fight;

But what a shining animal is man,

Who knows, when pain subsides, that is not that,

For worse than that must follow—yet can write

Music; can laugh; play tennis; even plan.

Edna St. Vincent Millay's Read history

Edna St. Vincent Millay’s sonnet “Read History” is a compact yet profound meditation on human existence, resilience, and the paradoxical grandeur of mankind in the face of cosmic insignificance. Written in Millay’s characteristically sharp and lyrical style, the poem balances existential despair with a call to dignity, urging humanity to persist despite its fragility. Through its interplay of historical awareness, stoic resolve, and artistic defiance, the poem encapsulates a modernist sensibility—acknowledging the vast indifference of the universe while affirming the fleeting beauty of human endeavor.

Historical and Biographical Context

Millay, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet of the early 20th century, was known for her rebellious spirit, feminist leanings, and engagement with both romanticism and modernist disillusionment. Born in 1892, she came of age during a period of immense social upheaval—World War I, the rise of industrialization, and the gradual erosion of traditional certainties. Her work often grapples with themes of mortality, love, and defiance, blending classical forms with contemporary concerns.

“Read History” reflects this tension between classical restraint and modern existential anxiety. The poem’s directive to “Read history” suggests a confrontation with humanity’s repetitive cycles of struggle, a theme that resonated in the interwar period when many artists and intellectuals questioned human progress. The poem does not offer easy consolation but instead presents a stark yet oddly uplifting vision of human tenacity.

Themes and Philosophical Underpinnings

1. Cosmic Insignificance and Human Defiance

The opening lines immediately establish humanity’s smallness in the universe:

“Read history: thus learn how small a space

You may inhabit, nor inhabit long”

History, in this reading, is not merely a record of events but a humbling lesson in transience. The vastness of the “crowding Cosmos” reduces human life to a “confined place,” echoing both Ecclesiastes’ “vanity of vanities” and the existentialist notion of an indifferent universe. Yet, rather than succumbing to despair, Millay urges action:

“Work boldly; build your flimsy barriers strong”

The oxymoron of “flimsy barriers” underscores the fragility of human constructs—civilizations, cultures, personal achievements—while the command to make them “strong” suggests a defiant will. This tension between futility and perseverance aligns with Albert Camus’ later philosophy of “The Myth of Sisyphus” (1942), where the act of rebellion itself grants meaning.

2. The Paradox of Human Nobility

Millay contrasts humanity with other creatures, particularly the rat, which fights instinctively in adversity. Humans, however, possess a tragic awareness of their doom:

“But what a shining animal is man,

Who knows, when pain subsides, that is not that,

For worse than that must follow”

The phrase “shining animal” evokes both admiration and irony—humans are glorious yet burdened by foresight. Unlike beasts that react only to immediate threats, humans anticipate suffering, yet they respond not just with survival instincts but with creativity:

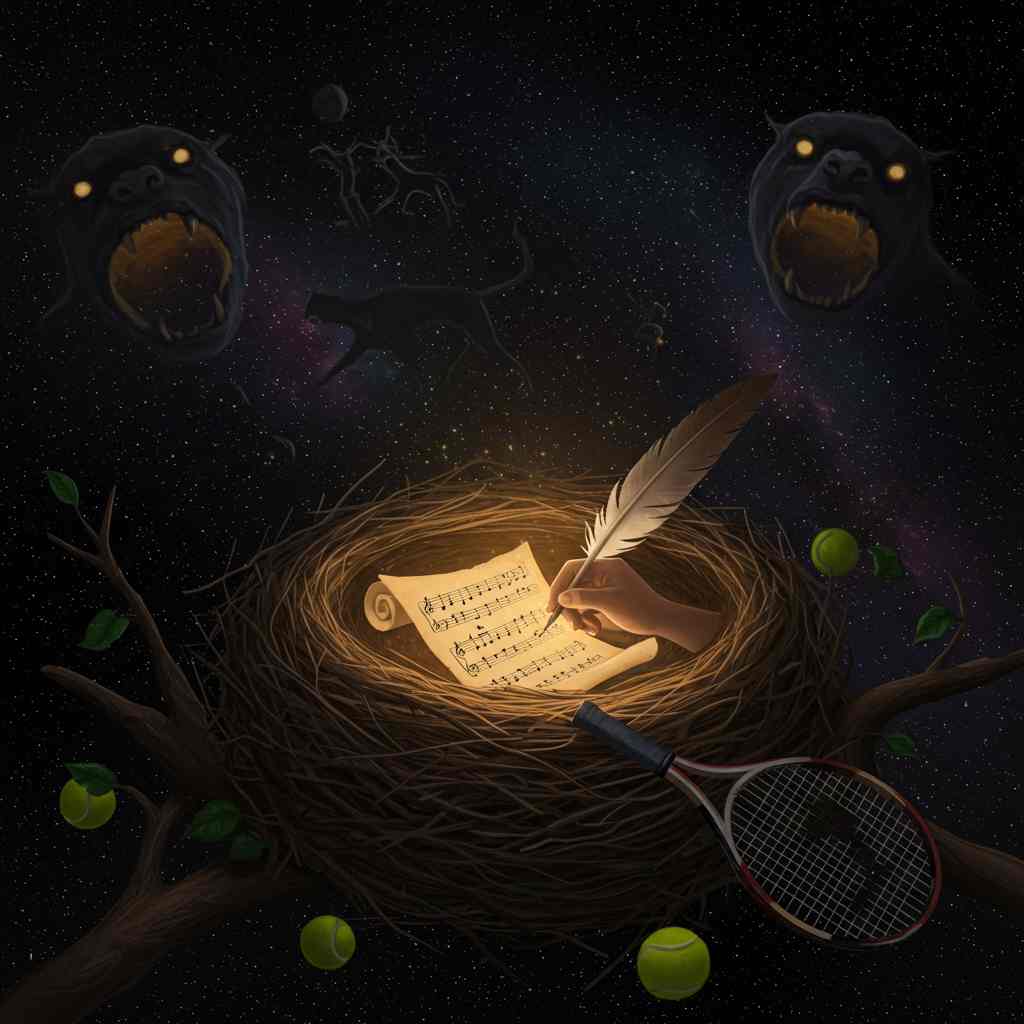

“—yet can write

Music; can laugh; play tennis; even plan.”

This closing catalog of human activities—art, joy, sport, foresight—serves as a testament to resilience. The juxtaposition of trivial pleasures (“play tennis”) with profound achievements (“write / Music”) suggests that meaning is found not in grand cosmic significance but in daily acts of beauty and persistence.

Literary Devices and Structure

Millay’s use of the sonnet form—traditionally associated with love and idealism—subverts expectations, turning it into a vehicle for existential contemplation. The poem’s volta, or turn, occurs subtly, shifting from a meditation on mortality to a celebration of human spirit.

1. Imagery and Diction

The poem’s imagery oscillates between confinement and expansiveness. The “confined place” of human existence contrasts with the “crowding Cosmos,” emphasizing both limitation and the vastness that renders us insignificant. The metaphor of building “flimsy barriers” suggests civilization itself is a fragile construct, yet the imperative to “make warm your nest” introduces a tender, almost nurturing counterpoint.

Millay’s diction is precise yet evocative. Words like “doomed and splendid race” capture the duality of human existence—both tragic and magnificent. The rat’s “courage” is instinctual, but man’s ability to “laugh” and “plan” implies consciousness, a higher-order resilience.

2. Tone and Irony

The tone is admonishing yet strangely uplifting. The speaker does not offer false comfort but instead insists on dignity despite inevitable suffering. There is irony in the phrase “shining animal,” which acknowledges human brilliance while undercutting it with the reminder that we are still mere animals, subject to the same forces as the lowly rat.

Comparative Readings

Millay’s poem resonates with other modernist and existentialist works. T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” (1922) similarly portrays history as a cyclical march of futility, though Eliot’s vision is bleaker. In contrast, Millay’s insistence on human creativity aligns more with Wallace Stevens’ “The Idea of Order at Key West”, where art imposes meaning on chaos.

Philosophically, the poem echoes Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of amor fati (love of fate)—embracing life’s struggles without illusion. The closing lines, celebrating music and laughter, recall Nietzsche’s assertion that “we have art so that we shall not die of the truth.”

Emotional Impact and Contemporary Relevance

“Read History” speaks to the modern reader with striking immediacy. In an age of climate crisis, political instability, and pandemic anxieties, Millay’s exhortation to “build your flimsy barriers strong” feels urgently relevant. The poem does not promise salvation but offers a way to endure—through art, community, and sheer stubbornness.

The emotional power lies in its refusal of both nihilism and naive optimism. It acknowledges suffering (“For worse than that must follow”) yet finds redemption in small, defiant acts. This balance makes the poem both sobering and strangely exhilarating—a call to live fully precisely because life is fleeting.

Conclusion

Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Read History” is a masterful fusion of existential dread and humanist resolve. Through its tight sonnet structure, rich imagery, and philosophical depth, the poem captures the paradox of human existence—our insignificance in the cosmos contrasted with our capacity for courage, creativity, and joy. It is a poem for all eras, but particularly for times of crisis, reminding us that while history may teach us our smallness, it is our response to that smallness that defines us.

In the end, Millay does not offer grand answers but something more valuable: a way to stand, unbroken, in the face of the infinite.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!