The Unfortunate Lover

Andrew Marvell

1621 to 1678

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

Alas, how pleasant are their days

With whom the infant Love yet plays!

Sorted by pairs, they still are seen

By fountains cool, and shadows green.

But soon these flames do lose their light,

Like meteors of a summer’s night:

Nor can they to that region climb,

To make impression upon time.

’Twas in a shipwreck, when the seas

Ruled, and the winds did what they please,

That my poor lover floating lay,

And, ere brought forth, was cast away:

Till at the last the master-wave

Upon the rock his mother drave;

And there she split against the stone,

In a Caesarean sectión.

The sea him lent those bitter tears

Which at his eyes he always wears;

And from the winds the sighs he bore,

Which through his surging breast do roar.

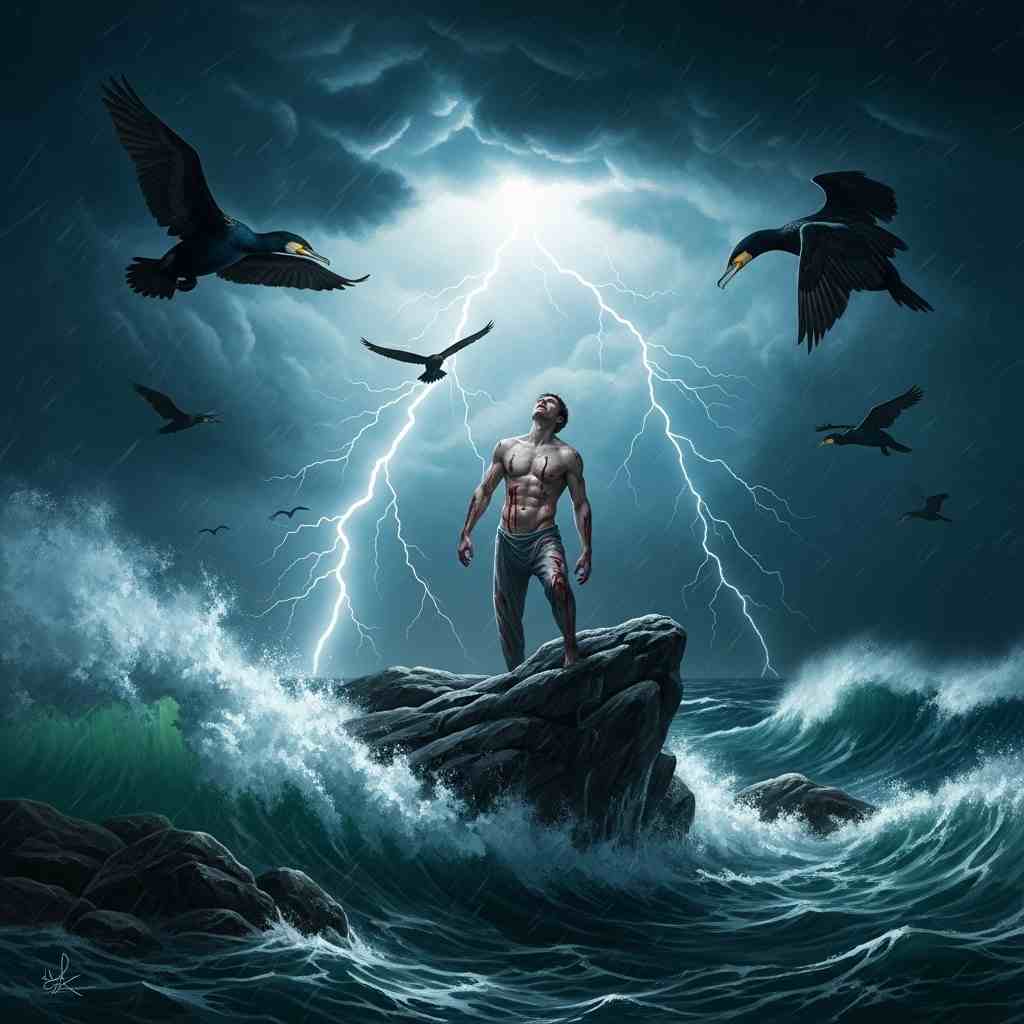

No day he saw but that which breaks

Through frighted clouds in forkèd streaks,

While round the rattling thunder hurled,

As at the funeral of the world.

While Nature to his birth presents

This masque of quarrelling elements,

A numerous fleet of cormorants black,

That sailed insulting o’er the wrack,

Received into their cruel care

Th’ unfortunate and abject heir:

Guardians most fit to entertain

The orphan of the hurricane.

They fed him up with hopes and air,

Which soon digested to despair,

And as one cormorant fed him, still

Another on his heart did bill,

Thus while they famish him, and feast,

He both consumèd, and increased:

And languishèd with doubtful breath,

The amphibíum of life and death.

And now, when angry heaven would

Behold a spectacle of blood,

Fortune and he are called to play

At sharp before it all the day:

And tyrant Love his breast does ply

With all his winged artillery,

Whilst he, betwixt the flames and waves,

Like Ajax, the mad tempest braves.

See how he nak’d and fierce does stand,

Cuffing the thunder with one hand,

While with the other he does lock,

And grapple, with the stubborn rock:

From which he with each wave rebounds,

Torn into flames, and ragg’d with wounds,

And all he says, a lover dressed

In his own blood does relish best.

This is the only banneret

That ever Love created yet:

Who though, by the malignant stars,

Forcèd to live in storms and wars,

Yet dying leaves a perfume here,

And music within every ear:

And he in story only rules,

In a field sable a lover gules.

Andrew Marvell's The Unfortunate Lover

Andrew Marvell’s The Unfortunate Lover is a striking and enigmatic poem that explores themes of love, fate, suffering, and the cruel caprices of nature. Written in the mid-17th century, the poem stands as a testament to Marvell’s mastery of metaphysical conceit, his ability to weave elaborate and often startling imagery into a meditation on human experience. The poem’s central figure—the "unfortunate lover"—is a tragic hero whose very existence is marked by violence, abandonment, and relentless struggle. Through this figure, Marvell interrogates the nature of love, the inevitability of suffering, and the paradoxical beauty found in endurance.

This analysis will examine the poem’s historical and literary context, its rich use of imagery and metaphor, its thematic preoccupations, and its emotional resonance. Additionally, we will consider how Marvell’s work engages with broader philosophical and poetic traditions, particularly the metaphysical poets’ fascination with paradox and the sublime.

Historical and Literary Context

Marvell wrote The Unfortunate Lover during a period of immense political and social upheaval in England—the mid-1600s, a time of civil war, regicide, and the eventual restoration of the monarchy. This era was marked by uncertainty, violence, and shifting allegiances, themes that resonate deeply in the poem. The lover’s tumultuous birth, his abandonment to the elements, and his ceaseless battle against hostile forces mirror the instability of Marvell’s own time.

Moreover, the poem fits within the tradition of metaphysical poetry, a movement characterized by intellectual complexity, elaborate conceits, and a blending of the sensual and the philosophical. Like John Donne and George Herbert, Marvell employs startling imagery—shipwrecks, storms, predatory birds—to explore abstract ideas about love and suffering. The poem’s extended metaphor of the lover as a storm-tossed, wounded figure aligns with the metaphysical poets’ tendency to fuse the physical and the spiritual in unexpected ways.

Imagery and Symbolism: A World of Violence and Paradox

From its opening lines, The Unfortunate Lover establishes a stark contrast between the idyllic love of ordinary couples and the brutal fate of its protagonist. The poem begins with an evocation of carefree lovers who "play" by "fountains cool and shadows green," only to dismiss them as fleeting, their love as transient as "meteors of a summer’s night." This pastoral imagery serves as a foil to the violent, elemental world the unfortunate lover inhabits.

The lover’s origin story is one of trauma: he is born from a shipwreck, "cast away" before he is even fully brought into existence. The description of his birth—"a Gæsarian section"—is particularly striking. The term "Gæsarian" evokes both Caesar (suggesting a violent, unnatural birth) and the word "caesura," a rupture or break. This linguistic play underscores the lover’s fractured existence, torn from the womb of the sea in an act of destruction rather than creation.

The natural world in the poem is not benign but actively hostile. The sea grants him "bitter tears," the winds fill him with sighs that "roar" through his breast, and the thunder rolls as if at "the funeral of the world." Nature here is not a nurturing force but a participant in his suffering, staging a "masque of quarrelling elements" at his birth. This theatrical metaphor suggests that his life is a performance of agony, scripted by indifferent or malevolent forces.

The cormorants, often symbols of greed and predation, become his cruel guardians, feeding him "hopes and air" that turn to despair. The paradoxical nature of his existence is captured in the lines:

"Thus, while they famish him, and feast,

He both consumed, and increased,

And languished with doubtful breath,

The amphibium of life and death."

Here, Marvell presents the lover as a liminal being, caught between states—neither fully alive nor dead, sustained by the very forces that destroy him. The term "amphibium" (literally, "living both ways") reinforces this duality, suggesting a creature that belongs to neither land nor sea, much like the lover, who exists in a perpetual state of suffering.

The Lover as Tragic Hero: Love, War, and the Sublime

The latter half of the poem shifts into a more explicitly heroic—or anti-heroic—register. The lover is cast as a warrior, battling both the elements and Love itself, personified as a tyrant wielding "winged artillery." The reference to Ajax, the Greek hero who fought the Trojans in a frenzy, aligns the lover with classical tragedy. Like Ajax, he is both noble and doomed, raging against forces he cannot overcome.

The imagery becomes increasingly visceral:

"See how he naked and fierce does stand,

Cuffing the thunder with one hand,

While with the other he does lock,

And grapple, with the stubborn rock."

This is a portrait of defiance in the face of annihilation. The lover is "naked," exposed to the full brutality of existence, yet he fights back, even as each wave tears him into "flames" and leaves him "ragged with wounds." The paradoxical beauty of his suffering is encapsulated in the startling assertion that "a lover drest / In his own blood does relish best." Here, Marvell suggests that there is a perverse dignity in enduring love’s torments, that the lover’s very wounds become his adornment.

The poem’s closing lines elevate the lover to a mythic status:

"And he in story only rules,

In a field sable, a lover gules."

The heraldic language ("sable" for black, "gules" for red) immortalizes him as a figure of legend—a knight whose emblem is his own bloodied form. Unlike the fleeting happiness of ordinary lovers, his suffering ensures his place in memory.

Themes: Love, Fate, and the Aesthetics of Suffering

At its core, The Unfortunate Lover is a meditation on the nature of love as an inescapable, often destructive force. The poem rejects the conventional pastoral ideal of love as harmonious and idyllic, instead presenting it as a battlefield where the lover is both combatant and casualty.

Fate and free will are also at play. The lover is "forced to live in storms and wars" by "malignant stars," suggesting a predestined suffering. Yet his defiance—his willingness to "cuff the thunder" and "grapple with the rock"—implies a kind of agency, however futile.

Finally, the poem engages with the aestheticization of suffering. The lover’s agony is rendered in vivid, almost beautiful terms—his blood is a "perfume," his cries become "music." This aligns with the Baroque fascination with martyrdom and the sublime, where pain is transfigured into art.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Marvell’s Vision

The Unfortunate Lover is a poem of extraordinary intensity, blending violent imagery with profound metaphysical inquiry. Marvell’s lover is a figure of both pathos and grandeur, his suffering rendered with a brutal yet lyrical precision. In its exploration of love’s cruelty, the caprices of fate, and the strange beauty of endurance, the poem remains a powerful and unsettling work.

Marvell does not offer consolation—his lover is not redeemed but enshrined in his torment. Yet there is a perverse triumph in this: the lover’s story outlasts the fleeting joys of others. In this way, the poem speaks to the enduring human fascination with tragedy, with the idea that there is something noble, even beautiful, in the act of resistance against an indifferent universe.

Four centuries after its composition, The Unfortunate Lover continues to resonate, a testament to poetry’s ability to capture the most extreme and contradictory of human experiences.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more