Now I am on the earth

Arthur O'Shaughnessy

1844 to 1881

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

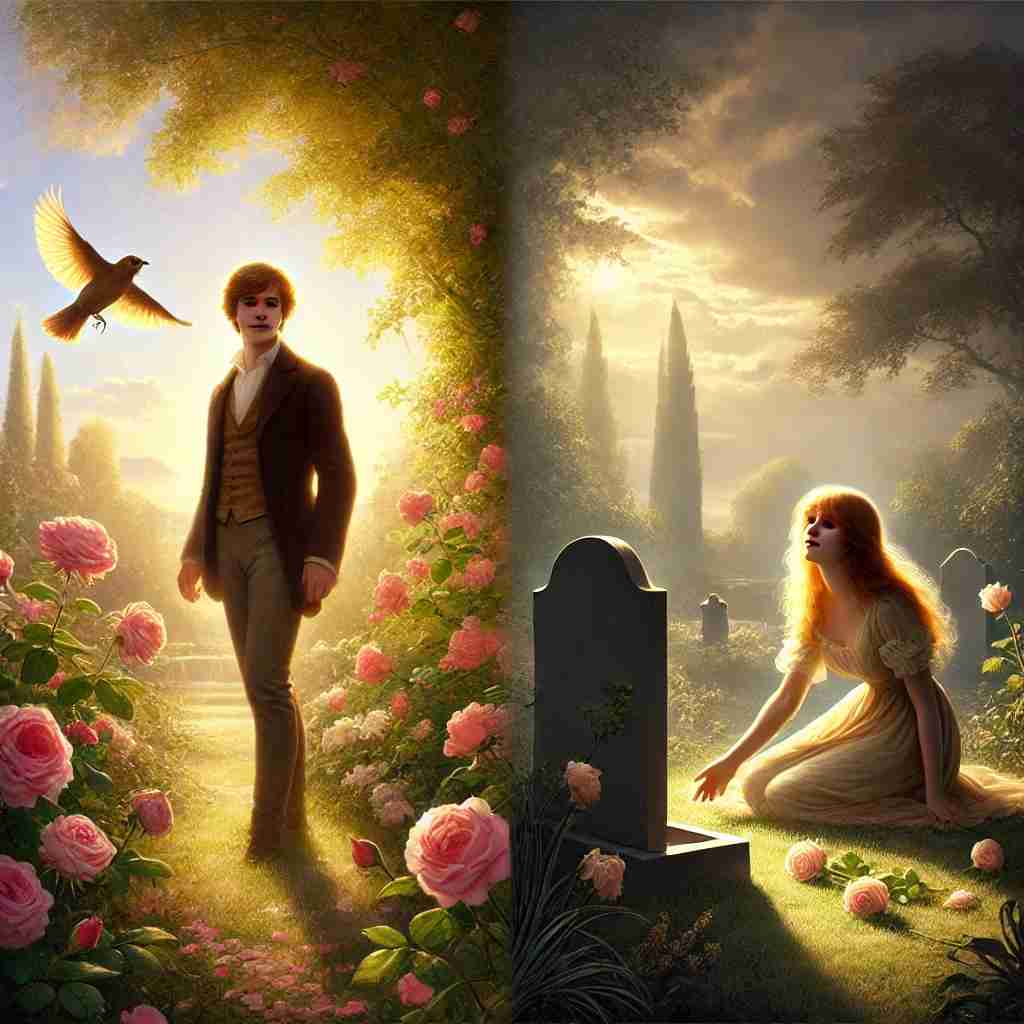

Now I am on the earth,

What sweet things love me?

Summer, that gave me birth,

And glows on still above me;

The bird I loved a little while;

The rose I planted;

The woman in whose golden smile

Life seems enchanted.

Now I am in the grave,

What sweet things mourn me?

Summer, that all joys gave,

Whence death, alas! hath torn me;

One bird that sang to me; one rose

Whose beauty moved me;

One changeless woman; yea, all those

That living loved me.

Arthur O'Shaughnessy's Now I am on the earth

Arthur O'Shaughnessy’s Now I am on the earth is a deceptively simple lyric that distills profound existential questions into two concise stanzas. Written during the Victorian era’s preoccupation with mortality and artistic permanence, the poem juxtaposes life’s ephemeral joys with death’s isolating finality, using tightly controlled imagery and structural parallelism to explore themes of transience, legacy, and the paradoxical constancy of human connection.

Historical and Cultural Context

As a herpetologist-poet employed at the British Museum, O’Shaughnessy straddled the Victorian age’s scientific rationalism and Romantic idealism26. The poem’s duality-contrasting life’s sensory richness with death’s starkness-mirrors the era’s tension between Darwinian impermanence and the Pre-Raphaelite pursuit of eternal beauty39. His position as an "outsider" within both scientific and artistic circles (due to his Irish heritage and rumored illegitimacy)29 infuses the work with a longing for belonging that transcends mortality. The poem’s focus on nature’s cyclicality (“Summer, that gave me birth”) aligns with Victorian ecological awareness, while its introspective tone reflects the period’s spiritual uncertainty post-Origin of Species.

Structural and Literary Devices

The poem’s mirror structure-two octaves with parallel interrogatives-creates a dialectic between life and death:

| Life (Stanza 1) | Death (Stanza 2) |

|---|---|

| “What sweet things love me?” | “What sweet things mourn me?” |

| Summer’s vitality | Summer’s loss |

| Plural joys (“rose,” “bird”) | Singular remnants (“one rose”) |

| “enchanted” existence | “torn” separation |

This chiasmus underscores life’s fragmentation into death’s narrowed reality. The shift from active verbs (“glows,” “planted”) to passive constructions (“hath torn me”) amplifies the speaker’s posthumous powerlessness.

Symbolism operates on multiple levels:

-

Summer: Represents both life’s zenith and time’s inexorable flow, echoing Keatsian seasonal metaphors while subverting them through personification (“gave me birth”)410.

-

Rose and bird: Traditional Romantic symbols of beauty and song acquire darker resonance in death, becoming relics of memory rather than living entities.

-

Golden smile: The woman’s immutable allure contrasts with the speaker’s mortality, evoking Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s idealized yet haunting feminine figures39.

Paradox drives the emotional core: the “changeless woman” embodies both comfort (her loyalty) and anguish (her inability to join the speaker in death). This duality reflects O’Shaughnessy’s broader exploration of art’s capacity to immortalize fleeting moments710.

Thematic Analysis

1. The Illusion of Permanence

The poem interrogates what endures beyond individual existence. Nature’s cycles (“Summer […] glows on still”) mock human transience, while the speaker’s creations-the planted rose, the beloved woman-become fragile memorials. This tension mirrors O’Shaughnessy’s own struggle to reconcile his taxonomic work (classifying permanent species) with poetry’s ephemeral impact36. The closing line, “That living loved me,” hints at communal memory as the only true afterlife-a radical departure from Victorian spiritualism.

2. Art as Counter-Entropy

Though the speaker’s physical presence dissolves, their artistic legacy persists through curated images: the rose they planted, the bird they cherished. This aligns with O’Shaughnessy’s belief (expressed in Ode) that artists “dwell apart” yet shape eternity through creativity410. The woman’s “changeless” smile functions as a living artwork, defying time’s erosion much like the British Museum’s preserved specimens29.

3. The Burden of Consciousness

The poem’s interrogative mode (“What sweet things…?”) reveals existential anxiety. In life, the speaker questions love’s sources; in death, they seek validation through mourning. This echoes Schopenhauerian themes of desire as suffering7, with the grave becoming a site of audit rather than rest. The shift from plural (“sweet things”) to singular (“one bird”) in death suggests that consciousness narrows into solipsism when stripped of life’s sensory tapestry.

Biographical and Philosophical Resonances

O’Shaughnessy’s personal losses-his two infant children and wife Eleanor’s early death6-haunt the poem’s subtext. The “woman” figure’s dual role as life’s enchantress and death’s mourner parallels Eleanor’s influence: her presence in his Toyland collaborations symbolized creative partnership, while her absence left him “torn” like summer’s departure69.

Philosophically, the poem engages with Epicurean thought: the speaker neither fears nor glorifies death but assesses it as a natural transition. The repeated “now” (a temporal anchor in both stanzas) suggests a present-tense existence that negates linear time-a concept later explored by T.S. Eliot, who admired O’Shaughnessy’s ability to crystallize profound ideas in sparse form24.

Comparative Perspectives

-

Vs. Emily Dickinson: Both poets use deceptively simple structures to explore mortality, but where Dickinson’s dashes create rhythmic uncertainty, O’Shaughnessy’s couplets impose order on chaos. His “changeless woman” contrasts with Dickinson’s mutable personifications of death.

-

Vs. Alfred, Lord Tennyson: In In Memoriam, Tennyson seeks solace in nature’s cycles; O’Shaughnessy’s speaker finds no such assurance, with summer’s continuity highlighting human fragility.

-

Vs. Christina Rossetti: Rossetti’s Remember implores forgetfulness, while O’Shaughnessy’s speaker demands remembrance-a gendered contrast reflecting Victorian male anxiety about legacy37.

Emotional Impact

The poem’s power lies in its restraint. By avoiding grand metaphors, it amplifies the pathos of small losses: a single rose, one bird’s song. The woman’s “golden smile” lingers as a synesthetic imprint, merging visual and emotional resonance. Readers confront the paradox that love-the very force that “enchants” life-intensifies grief, making the speaker’s death not an end but a transformation of relationships.

Conclusion

Now I am on the earth exemplifies O’Shaughnessy’s ability to compress vast existential inquiries into crystalline verse. Its interplay of structural symmetry and thematic asymmetry reflects the Victorian age’s conflicted soul-torn between faith in progress and awareness of impermanence. By grounding cosmic questions in intimate imagery (a rose, a smile), the poem achieves universal resonance, inviting readers to ponder what, if anything, survives life’s “summer” when winter inevitably comes. As both artifact and living voice, it embodies O’Shaughnessy’s conviction that poetry outlasts even the most meticulously cataloged specimens of science239.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more