Vespers

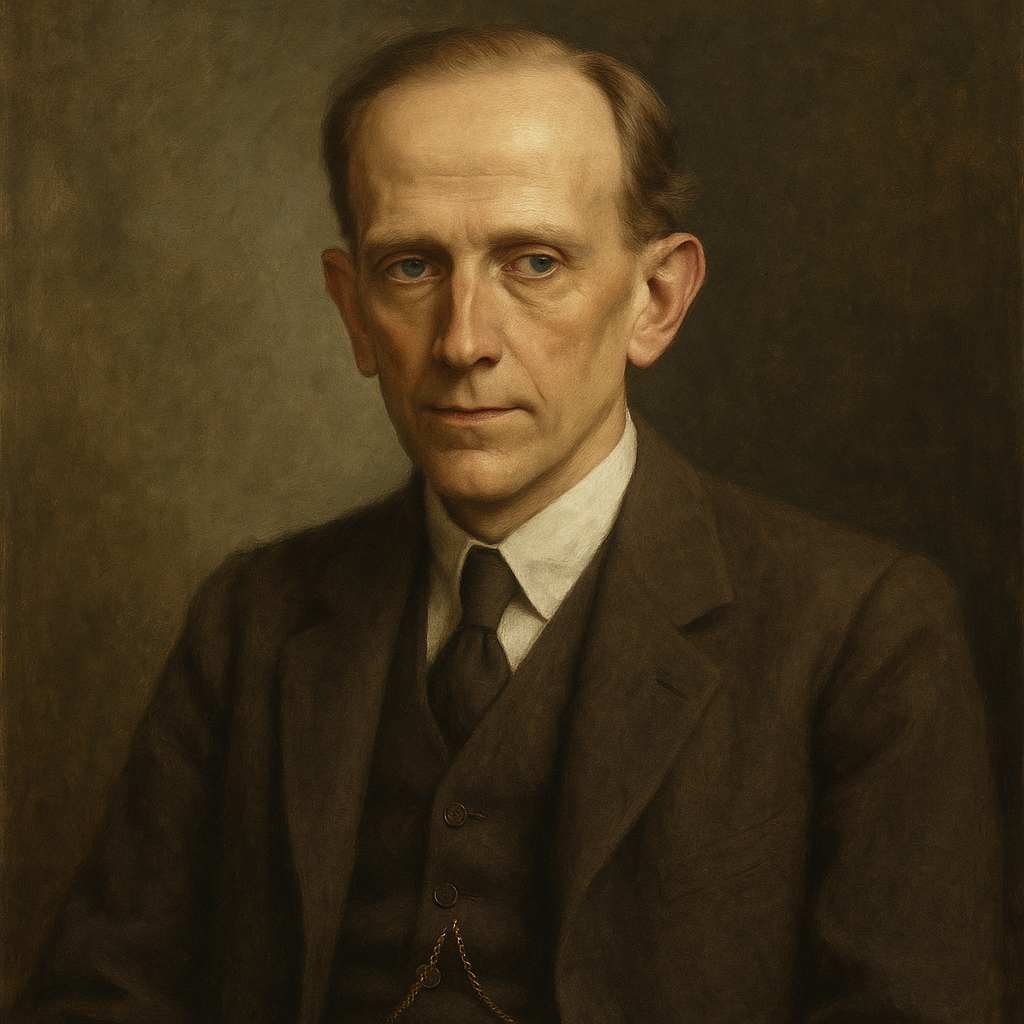

A. A. Milne

1882 to 1956

Little Boy kneels at the foot of the bed,

Droops on the little hands little gold head.

Hush! Hush! Whisper who dares!

Christopher Robin is saying his prayers.

God bless Mummy. I know that's right.

Wasn't it fun in the bath to-night?

The cold's so cold, and the hot's so hot.

Oh! God bless Daddy—I quite forgot.

If I open my fingers a little bit more,

I can see Nanny's dressing-gown on the door.

It's a beautiful blue, but it hasn't a hood.

Oh! God bless Nanny and make her good.

Mine has a hood, and I lie in bed,

And pull the hood right over my head,

And I shut my eyes, and I curl up small,

And nobody knows that I'm there at all.

Oh! Thank you, God, for a lovely day.

And what was the other I had to say?

I said "Bless Daddy," so what can it be?

Oh! Now I remember it. God bless Me.

Little Boy kneels at the foot of the bed,

Droops on the little hands little gold head.

Hush! Hush! Whisper who dares!

Christopher Robin is saying his prayers.

A. A. Milne's Vespers

A Scholarly Analysis of A. A. Milne’s “Vespers”

A. A. Milne’s “Vespers” stands as a quintessential example of early twentieth-century children’s poetry, notable for its blend of sentimentality, psychological insight, and cultural resonance. First published in 1923 in Vanity Fair and later included in Milne’s celebrated collection When We Were Very Young (1924), “Vespers” captures a moment of childhood ritual-bedtime prayer-through the figure of Christopher Robin, a character modeled on Milne’s own son136. This essay explores the poem’s historical and cultural context, literary devices, themes, and emotional impact, while situating it within both the personal biography of its author and the broader tradition of children’s literature.

Historical and Cultural Context

Britain in the Early Twentieth Century

“Vespers” emerges from a period in British history marked by profound social and cultural shifts. The aftermath of World War I had left the nation grappling with loss and uncertainty, yet also seeking solace in tradition and domesticity. The 1920s, often referred to as the interwar years, saw a resurgence of interest in the innocence of childhood, perhaps as a reaction to the trauma of war and the anxieties of modernity34. Children’s literature became a vehicle for nostalgia, escapism, and the reaffirmation of values perceived as under threat.

Religious Ritual and Social Norms

The title “Vespers” refers to the evening prayer service in Christian liturgy, particularly within the Anglican, Catholic, and Orthodox traditions27. In early twentieth-century Britain, such rituals were commonplace, reflecting the pervasive influence of Christianity on daily life. The poem’s depiction of a child at prayer thus evokes a familiar domestic scene, one that would have resonated with contemporary readers as both ordinary and sacred. Yet, as critics have noted, Milne’s treatment of the subject is gently subversive: while the trappings of piety are present, the child’s thoughts are elsewhere, revealing the gap between ritual and genuine devotion17.

The Cult of the “Beautiful Child”

Humphrey Carpenter, a prominent literary critic, situates “Vespers” at the tail end of a fifty-year Victorian-Edwardian tradition that idealized the “Beautiful Child”-innocent, angelic, and morally pure1. Milne’s poem initially appears to conform to this tradition, but a closer reading reveals a more nuanced portrayal, one that acknowledges the child’s wandering attention and inner life.

Biographical Insights

A Father’s Gaze

Milne’s inspiration for “Vespers” was intensely personal. He wrote the poem after observing his two-year-old son, Christopher Robin Milne, being taught to pray by his nanny14. The scene struck him as both touching and somewhat hollow, as he realized that the child was reciting words by rote, with little understanding of their meaning. The poem was originally a gift to his wife, Daphne, and only later published-an origin that underscores its intimate, domestic roots1.

Christopher Robin’s Perspective

The real Christopher Robin later expressed ambivalence, even resentment, toward the poem and the fame it brought him. In his memoir, he described “Vespers” as a “wretched poem,” feeling that it misrepresented his inner experience and contributed to a public persona with which he struggled to identify15. This tension between the private and the public, the authentic and the performed, adds a poignant layer to the poem’s legacy.

Literary Devices

Imagery and Sensory Detail

Milne’s language is marked by vivid, concrete imagery that grounds the poem in the sensory world of the child. The “little gold head” drooping on “little hands,” the “beautiful blue” dressing-gown, the sensations of hot and cold in the bath-all evoke the immediacy of childhood experience2. These details are not merely decorative; they serve to anchor the poem’s emotional truth in the particulars of daily life.

Enjambment and Caesura

The poem’s lines often spill over into one another (enjambment), mirroring the child’s wandering thoughts2. Caesura-pauses within lines-further disrupts the flow, capturing the fits and starts of a child’s attention. For example, “Oh! God bless Daddy-I quite forgot,” uses the dash to signal a moment of recollection, both comic and endearing.

Repetition and Circularity

The first and last stanzas are identical, framing the poem with a sense of ritual and return12. This circular structure echoes the repetitive nature of bedtime routines and underscores the theme of innocence preserved within the cycles of daily life. The refrain “Hush! Hush! Whisper who dares! / Christopher Robin is saying his prayers” invites the reader to witness, but not intrude upon, this private moment.

Allusion and Anaphora

Milne employs allusion through the poem’s title and the invocation of prayer, situating the work within a broader religious and literary tradition2. Anaphora-the repetition of words at the beginning of successive lines, such as “And” in the fourth stanza-reinforces the child’s simple, cumulative style of thinking and speaking.

Alliteration and Sound Play

The poem features frequent alliteration (“little hands little gold head,” “beautiful blue”), which adds musicality and reinforces the childlike tone2. This sonic texture is both playful and soothing, contributing to the poem’s lullaby-like quality.

Themes

Innocence and Distraction

At its core, “Vespers” is a meditation on the nature of childhood innocence. The poem simultaneously celebrates and gently mocks the child’s inability to focus on the solemnity of prayer. Christopher Robin’s mind drifts from blessing his mother to recalling the pleasures of his bath, to noticing the color of his nanny’s dressing-gown, to the comfort of his own hooded nightgown2. This stream-of-consciousness approach captures the authenticity of a child’s inner life, unfiltered and unselfconscious.

Ritual and Meaning

The poem raises subtle questions about the relationship between ritual and meaning. While the outward form of prayer is observed, the child’s thoughts are elsewhere, suggesting that the true significance of such rituals may lie not in their content but in their role as expressions of love, security, and routine17. The act of praying becomes less about theological conviction and more about participating in a shared family tradition.

Family and Belonging

Each stanza is anchored in relationships: “God bless Mummy,” “God bless Daddy,” “God bless Nanny,” and finally, “God bless Me.” The progression from others to self reflects both the egocentrism of early childhood and the gradual expansion of empathy. The prayer is as much a catalogue of the people who constitute the child’s world as it is a petition for divine favor.

Selfhood and Solitude

The stanza in which Christopher Robin pulls his hood over his head and “curl[s] up small / And nobody knows that I’m there at all” introduces a note of solitude and self-sufficiency. This moment of withdrawal is both comforting and slightly melancholic, hinting at the child’s desire for privacy and the beginnings of an inner life distinct from the adult gaze.

Memory and Nostalgia

For adult readers, “Vespers” evokes nostalgia for the lost world of childhood, with its rituals, comforts, and anxieties. The poem’s enduring popularity owes much to its ability to conjure up personal memories of being tucked into bed, reciting prayers, and inhabiting a world structured by the rhythms of family life17.

Emotional Impact

For Children

The simplicity of the language and the gentle humor make “Vespers” accessible and appealing to children7. The poem validates their experience, acknowledging the difficulty of maintaining focus and the tendency to mix the sacred and the mundane. The repeated refrain reassures children that their rituals are important, even if imperfectly performed.

For Adults

Adults reading “Vespers” to children-or recalling it from their own childhood-are likely to experience a complex mix of emotions: amusement at the child’s distractions, tenderness at the depiction of innocence, and perhaps a pang of loss for the simplicity of earlier days. The poem’s sentimentality has been both celebrated and criticized; some have found it saccharine, while others cherish its evocation of familial love and security1.

Irony and Ambivalence

Milne’s own attitude toward the poem was ambivalent. He recognized that its popularity had made it a target for parody and derision, with critics accusing it of excessive sweetness or shallow piety1. Yet, the poem’s subtle irony-its awareness that the child is not truly praying, but performing-lends it a complexity that belies its surface simplicity.

Comparative and Philosophical Perspectives

Comparison with Victorian Children’s Poetry

“Vespers” can be fruitfully compared to earlier works such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses or Christina Rossetti’s devotional poems for children. Like Stevenson, Milne adopts the child’s perspective, privileging immediacy and authenticity over didacticism. Unlike the more overtly moralizing tone of much Victorian verse, however, Milne’s poem is marked by a gentle irony and psychological realism.

Philosophical Reflections on Ritual and Authenticity

The poem invites philosophical reflection on the nature of ritual, particularly as practiced by children. Is the value of prayer diminished by inattention, or does the very act of participating in ritual confer meaning, regardless of the participant’s understanding? Milne seems to suggest that the latter is true: the ritual is valuable not for its content, but for its role in structuring experience and expressing connection.

The Child as Performer and Observer

“Vespers” also anticipates later psychological theories about the performative nature of childhood. Christopher Robin is both subject and object-he prays, but he is also aware of being observed (“Hush! Hush! Whisper who dares!”). The poem’s framing stanzas reinforce this duality, inviting the reader to witness the scene while simultaneously insisting on its privacy.

Legacy and Reception

Immediate and Enduring Popularity

Upon its publication, “Vespers” was an immediate success, motivating Milne to write more about Christopher Robin and eventually leading to the creation of the Winnie-the-Pooh stories16. The poem was set to music and widely recorded, becoming a staple of children’s literature in Britain and beyond.

Criticism and Parody

Despite-or perhaps because of-its popularity, “Vespers” attracted criticism for its sentimentality. It was parodied by writers such as Beachcomber, who lampooned its earnestness with lines like “Hush, hush, nobody cares / Christopher Robin has fallen downstairs”1. Yet, the poem’s resilience in the face of such mockery attests to its deep emotional resonance.

Personal and Public Tensions

The poem’s legacy is complicated by the real Christopher Robin’s discomfort with his literary alter ego. His sense of having been exploited for literary fame adds a note of melancholy to the poem’s reception history, reminding readers of the tensions between art and life, public and private selves5.

Conclusion

“Vespers” endures as a minor masterpiece of children’s poetry, remarkable for its psychological acuity, formal elegance, and emotional depth. Milne’s portrayal of Christopher Robin at prayer is at once affectionate and ironic, sentimental and subversive. The poem captures the paradoxes of childhood: innocence and egocentrism, ritual and distraction, belonging and solitude. Its historical and cultural context-postwar Britain, the cult of the Beautiful Child, the rituals of domestic piety-infuse it with layers of meaning that continue to resonate with readers of all ages.

By blending the particular (the child’s distracted prayers) with the universal (the longing for comfort, connection, and meaning), Milne creates a work that is both rooted in its time and timeless in its appeal. “Vespers” invites us to remember our own childhood rituals, to reflect on the nature of faith and family, and to cherish the fleeting moments of innocence that define our earliest years. In doing so, it affirms the enduring power of poetry to capture the complexities of human experience with grace, humor, and compassion127.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!