The Garden Party

Hilaire Belloc

1870 to 1953

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

The rich arrived in pairs

And also in Rolls Royces

They talked of their affairs

In loud and strident voices.

The poor arrived in Fords

Whose features they resembled

And laughed to see so many lords

And ladies all assembled.

The people in between

Looked underdone and harassed

And out of place and mean

And horribly embarrassed.

Hilaire Belloc's The Garden Party

Introduction

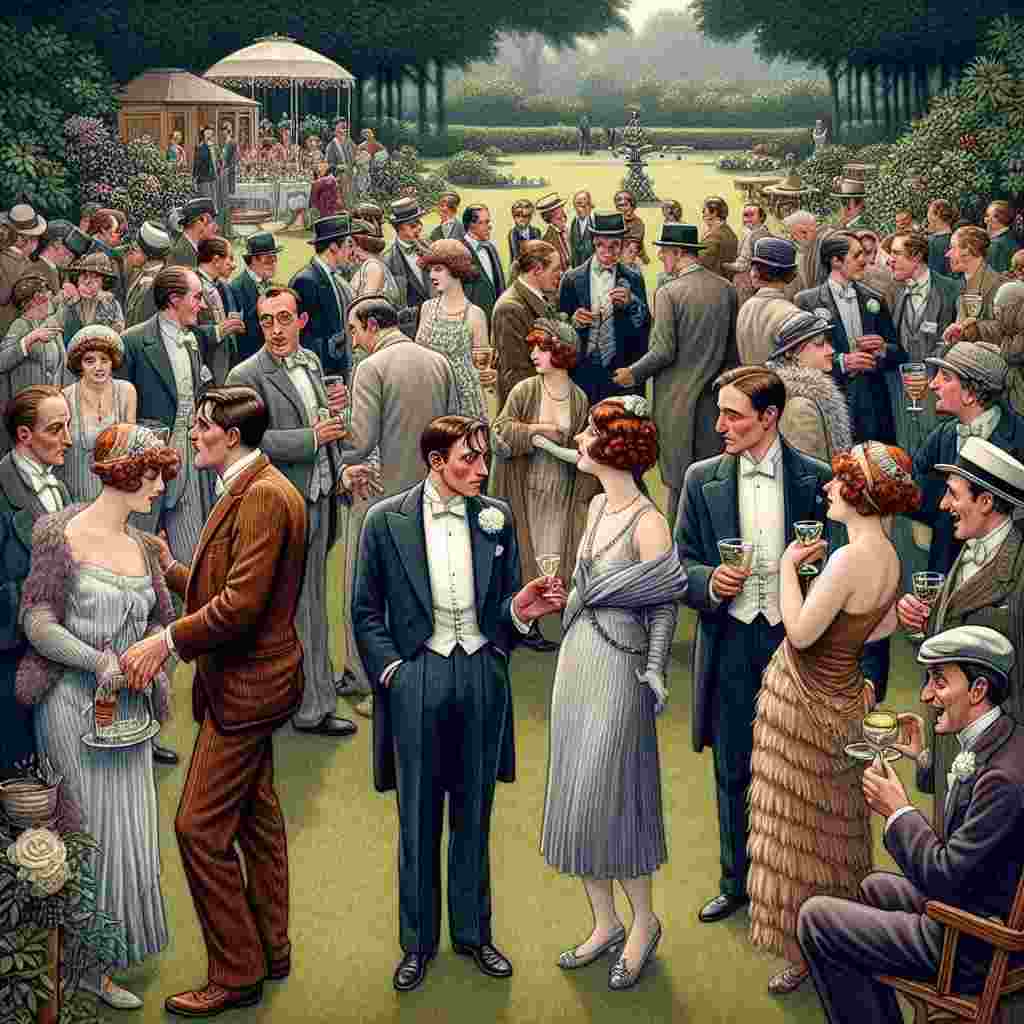

Hilaire Belloc's satirical poem "The Garden Party" offers a scathing critique of early 20th-century British social hierarchy through its deceptively simple structure and biting wit. This analysis will delve into the poem's use of structure, imagery, and language to illuminate Belloc's commentary on class divisions and social expectations of the era. By examining the poem's three distinct stanzas, each representing a different social class, we will uncover the layers of meaning and social criticism embedded within this concise yet powerful work.

Historical and Literary Context

To fully appreciate "The Garden Party," one must consider Belloc's position as a Anglo-French writer and historian during a time of significant social change in Britain. The early 20th century saw the erosion of traditional class structures, with the rise of the middle class and increasing social mobility. Belloc, known for his conservative views and skepticism towards modern progress, uses this poem to cast a critical eye on these societal shifts.

The poem's setting of a garden party is particularly significant, as such events were often used as a means of displaying wealth and social status. By choosing this backdrop, Belloc creates a microcosm of society, allowing him to dissect and critique the interactions and attitudes of different social classes in a confined space.

Structure and Form

"The Garden Party" consists of three quatrains, each with an ABAB rhyme scheme. This structured form contrasts with the chaotic social dynamics described within the poem, creating a tension between order and disorder that mirrors the unstable social hierarchy being portrayed.

Each stanza is dedicated to a different social class: the rich, the poor, and those "in between." This tripartite structure reflects the traditional view of society as divided into upper, lower, and middle classes. However, Belloc subverts expectations by presenting the middle class last, emphasizing their awkward position in the social order.

The consistent meter and rhyme scheme across all three stanzas suggest a superficial equality, but the content of each stanza reveals stark differences in the experiences and perceptions of each group. This juxtaposition of form and content serves to highlight the artificial nature of social divisions and the absurdity of class-based prejudices.

Analysis of Stanza 1: The Rich

"The rich arrived in pairs / And also in Rolls Royces / They talked of their affairs / In loud and strident voices."

The opening stanza immediately establishes the presence and behavior of the upper class. The use of "pairs" suggests couples, implying a sense of exclusivity and partnership among the elite. The mention of Rolls Royces, a luxury car brand, serves as a tangible symbol of wealth and status.

Belloc's choice of the phrase "their affairs" is deliberately ambiguous, potentially referring to business matters or more scandalous personal relationships. This ambiguity hints at the complex and often hidden nature of upper-class social interactions.

The description of their voices as "loud and strident" is particularly telling. It suggests a lack of consideration for others and an assumption of their right to dominate social spaces. The alliteration of "strident voices" emphasizes the harsh and grating nature of their speech, reflecting Belloc's critical view of their behavior.

Analysis of Stanza 2: The Poor

"The poor arrived in Fords / Whose features they resembled / And laughed to see so many lords / And ladies all assembled."

The second stanza introduces the lower class, characterized by their arrival in Ford automobiles. The comparison between the people and their vehicles - "Whose features they resembled" - is a masterful use of imagery that dehumanizes the poor, reducing them to the level of mass-produced objects. This line can be interpreted as a commentary on the dehumanizing effects of industrialization on the working class.

However, Belloc subverts expectations by portraying the poor as amused rather than intimidated by the gathering of the elite. The verb "laughed" suggests a sense of detachment and perhaps even superiority, as they find humor in the pompous display before them. This laughter can be seen as a form of resistance, a refusal to be awed or cowed by the trappings of wealth and status.

The use of archaic terms like "lords" and "ladies" further emphasizes the outdated nature of the social hierarchy being observed, suggesting that the poor see through the artifice of these titles and find them somewhat ridiculous.

Analysis of Stanza 3: The Middle Class

"The people in between / Looked underdone and harassed / And out of place and mean / And horribly embarrassed."

The final stanza, focusing on the middle class, is perhaps the most biting in its critique. The phrase "people in between" immediately positions this group as lacking a clear identity, caught between two more defined social strata.

The string of adjectives used to describe the middle class - "underdone," "harassed," "out of place," "mean," and "horribly embarrassed" - creates a vivid picture of discomfort and social anxiety. The term "underdone" is particularly interesting, suggesting that the middle class is somehow incomplete or not fully formed, lacking the refinement of the upper class or the unselfconsciousness of the lower class.

The emphasis on their embarrassment highlights the precarious position of the middle class, constantly striving to fit in with the elite while fearing association with the poor. This stanza encapsulates the unique pressures faced by the middle class in navigating social situations where class distinctions are on display.

Language and Tone

Throughout the poem, Belloc employs simple, direct language that belies the complexity of his social commentary. The straightforward diction and short lines create a sense of immediacy and accessibility, allowing readers from all social backgrounds to engage with the poem's themes.

The tone shifts subtly across the three stanzas, moving from detached observation in the first, to amused commentary in the second, to something approaching pity in the third. This progression mirrors the changing perspective of the narrator, who seems to align more closely with the poor in their amusement at the social spectacle.

Belloc's use of irony is particularly effective in the contrast between the self-assured behavior of the rich and the laughter of the poor. This ironic juxtaposition serves to undermine the assumed superiority of the upper class, suggesting that their social position is more fragile and absurd than they realize.

Symbolism and Imagery

The poem is rich in symbolic imagery, with the most prominent symbols being the vehicles associated with each class. The Rolls Royces of the rich symbolize luxury, exclusivity, and excess, while the Fords of the poor represent mass production, functionality, and a lack of individuality. The absence of a specific vehicle for the middle class further emphasizes their lack of a clear identity or place in society.

The garden party itself serves as a microcosm of society, a controlled environment where class distinctions are put on display. The artificiality of this setting underscores the constructed nature of social hierarchies and the performative aspects of class identity.

Conclusion

"The Garden Party" stands as a masterful example of social satire, using its concise form and sharp wit to deliver a powerful critique of class divisions in early 20th-century British society. Through his careful structuring, vivid imagery, and nuanced use of language, Belloc creates a multi-layered poem that invites readers to question the foundations of social hierarchy and the authenticity of class-based identities.

The poem's enduring relevance lies in its ability to capture the universal human experiences of social anxiety, class consciousness, and the desire for belonging. By presenting a snapshot of a society in flux, Belloc challenges readers to consider their own place in social hierarchies and the arbitrary nature of class distinctions.

Ultimately, "The Garden Party" serves not only as a critique of its time but also as a timeless reminder of the complexities of social interaction and the often absurd nature of human attempts to categorize and separate ourselves from one another. In its brief twelve lines, Belloc captures the essence of social stratification and the human cost of maintaining such divisions, leaving readers with a powerful indictment of class-based society that resonates well beyond its historical context.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more