Alas, poor Yorick!

William Shakespeare

1564 to 1616

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio: a fellow

of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy: he hath

borne me on his back a thousand times; and now, how

abhorred in my imagination it is! my gorge rises at it.

Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft.

Where be your gibes now? your gambols? your songs?

your flashes of merriment, that were wont to set the table on a roar?

Not one now, to mock your own grinning? quite chap-fallen?

Now get you to my lady's chamber, and tell her, let her paint an inch thick,

to this favour she must come; make her laugh at that.

Prithee, Horatio, tell me one thing...

William Shakespeare's Alas, poor Yorick!

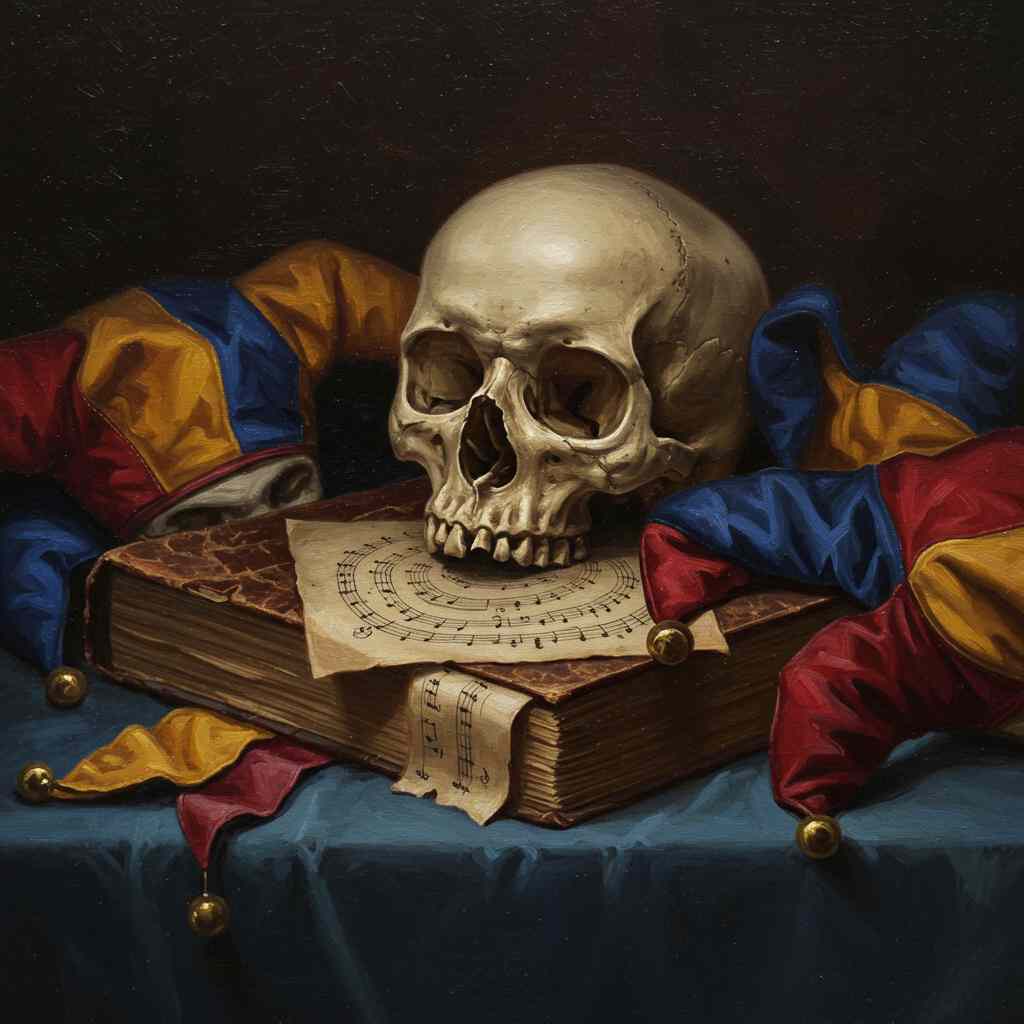

William Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a play steeped in existential contemplation, political intrigue, and profound meditations on life and death. Among its most iconic moments is Hamlet’s soliloquy upon encountering the skull of Yorick, the court jester of his childhood. This brief but deeply evocative speech—beginning with the famous line, "Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio"—serves as a microcosm of the play’s broader themes: the inevitability of death, the decay of the body, and the fleeting nature of human existence. Through this speech, Shakespeare not only advances Hamlet’s philosophical musings but also invites the audience to confront their own mortality.

Historical and Theatrical Context

To fully appreciate the significance of this passage, one must consider the cultural and historical backdrop of Renaissance England. The early 17th century was a period marked by a preoccupation with death, partly due to frequent outbreaks of plague, high infant mortality rates, and the religious upheavals of the Reformation. The memento mori tradition—artistic and literary reminders of death’s inevitability—was pervasive, and Shakespeare’s treatment of Yorick’s skull fits squarely within this tradition.

Moreover, the scene’s theatrical impact cannot be overstated. In Shakespeare’s time, the gravedigger scene (Act 5, Scene 1) would have been performed with a real prop skull, heightening the visceral immediacy of Hamlet’s meditation. The juxtaposition of the comic gravediggers with Hamlet’s solemn reflection creates a tonal shift that underscores the play’s central tension between levity and gravity, life and death.

Literary Devices and Rhetorical Craft

Shakespeare’s language in this passage is dense with rhetorical and poetic devices that amplify its emotional resonance. The speech begins with an exclamation—"Alas, poor Yorick!"—a phrase that immediately establishes a tone of lamentation. The use of the interjection "alas" signals sorrow, while the epithet "poor" evokes pity, framing Yorick not just as a deceased court jester but as a symbol of universal human frailty.

Hamlet’s recollection of Yorick as "a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy" employs hyperbole to emphasize the jester’s vivacity. The phrase "infinite jest" suggests boundless humor, while "most excellent fancy" conveys creativity and imagination. These descriptors paint Yorick as a figure of joy, making his present state—a lifeless skull—all the more jarring.

The contrast between past vitality and present decay is further heightened through tactile and sensory imagery. When Hamlet recalls how Yorick "hath borne me on his back a thousand times," the image is one of warmth, playfulness, and physical closeness. This stands in stark opposition to the revulsion Hamlet now feels: "how abhorred in my imagination it is! my gorge rises at it." The visceral reaction—"my gorge rises"—illustrates the body’s betrayal in death, a theme that recurs throughout the play (most notably in Hamlet’s disgust at his mother’s "incestuous" remarriage).

The rhetorical questions that follow—"Where be your gibes now? your gambols? your songs? your flashes of merriment?"—serve to underscore the irrevocable silence of death. The anaphora (repetition of "your") creates a rhythmic lament, each question reinforcing the absence of what once was. The phrase "set the table on a roar" is particularly poignant, as it evokes communal joy, now extinguished.

Perhaps the most striking moment in the speech is Hamlet’s observation that Yorick is "quite chap-fallen." The term "chap-fallen" carries a double meaning: literally, it refers to the slackened jaw of the skull, but figuratively, it suggests dejection or humiliation. Even in death, Hamlet anthropomorphizes Yorick, imagining him as if he were still capable of expression—only now, that expression is one of eternal silence.

Themes: Mortality, Decay, and the Illusion of Permanence

At its core, this passage is a meditation on the transience of life. Hamlet’s confrontation with Yorick’s skull forces him—and the audience—to reckon with the physical reality of death. The jester, once full of life and laughter, is now reduced to bones, a fate that awaits all, regardless of status or wit. This realization feeds into Hamlet’s broader existential crisis, as seen in his earlier soliloquies ("To be or not to be") and his fixation on corruption ("Something is rotten in the state of Denmark").

The speech also critiques societal attempts to deny or disguise death. Hamlet’s sardonic instruction—"Now get you to my lady’s chamber, and tell her, let her paint an inch thick, to this favour she must come"—mocks the vanity of those who seek to preserve youth and beauty through cosmetics. The phrase "an inch thick" exaggerates the futility of such efforts, as no amount of paint can stave off the decay that comes to all. The word "favour" here is ironic, as it typically connotes beauty or grace, but in this context, it refers to the grim visage of the skull.

This moment can be read as an extension of the vanitas tradition in art, where symbols of earthly pleasures (such as fine clothes, jewelry, or feasts) are juxtaposed with reminders of death (skulls, hourglasses, wilting flowers). Hamlet’s speech functions as a vanitas in verbal form, stripping away illusions to reveal the inevitability of decay.

Comparative and Philosophical Readings

Hamlet’s meditation on Yorick’s skull invites comparison with other philosophical and literary treatments of mortality. The most immediate parallel is with the Danse Macabre (Dance of Death) tradition, in which skeletons lead the living to their graves, emphasizing that death comes for all, regardless of station. Similarly, John Donne’s Holy Sonnets grapple with mortality, particularly in "Death, be not proud," where death itself is personified and diminished.

From a philosophical standpoint, Hamlet’s speech echoes the Stoic and existentialist notion that awareness of death gives life meaning. The French existentialist Albert Camus, in The Myth of Sisyphus, argues that confronting the absurdity of existence is necessary for authentic living. Hamlet, in holding Yorick’s skull, does precisely this—he stares into the void and, rather than turning away, uses it as a catalyst for deeper reflection.

Emotional Impact and Audience Connection

What makes this speech so enduringly powerful is its emotional universality. Every audience member, regardless of era, must confront the same reality Hamlet does: that life is fleeting, and death is the great equalizer. The personal nature of Hamlet’s address—"I knew him, Horatio"—makes the moment intimate, as if we, like Horatio, are being asked to bear witness to this truth.

The speech also balances profundity with dark humor. Hamlet’s macabre jest—"make her laugh at that"—suggests a grim comedy in the inevitability of death. This tonal duality is quintessentially Shakespearean, blending tragedy and wit in a way that deepens rather than diminishes the emotional weight.

Conclusion: The Legacy of "Alas, Poor Yorick!"

Centuries after its composition, Hamlet’s speech over Yorick’s skull remains one of the most quoted and analyzed moments in literature. Its power lies in its simplicity and depth—a prince holding a jester’s skull, confronting the inescapable fate that binds king and fool alike. Shakespeare, through Hamlet, does not offer easy consolation; instead, he forces us to look directly at death and, in doing so, to reflect on how we live.

In the end, Yorick’s skull is more than a prop—it is a mirror. When Hamlet gazes upon it, he sees not just his old friend, but himself, his father, his mother, and all of humanity. And when we, as readers or audience members, encounter this moment, we are invited to do the same. That is the genius of Shakespeare: he makes the universal personal, and the personal universal. "Alas, poor Yorick!" is not just Hamlet’s lament—it is ours.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more