My heart's in the Highlands

Robert Burns

1759 to 1796

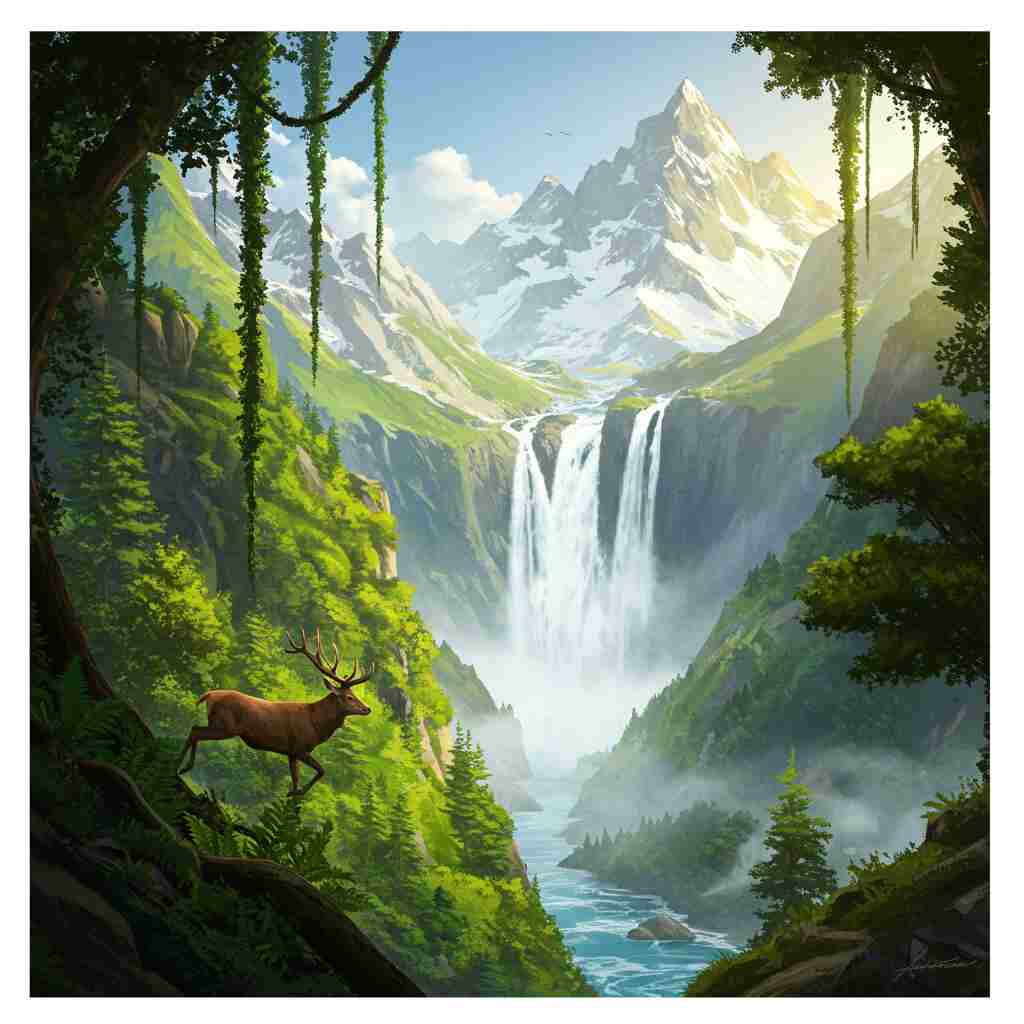

My heart's in the Highlands, my heart is not here;

My heart's in the Highlands a-chasing the deer;

A-chasing the wild deer, and following the roe--

My heart's in the Highlands wherever I go.

Farewell to the Highlands, farewell to the North,

The birth-place of valour, the country of worth;

Wherever I wander, wherever I rove,

The hills of the Highlands for ever I love.

Farewell to the mountains high cover'd with snow;

Farewell to the straths and green valleys below:

Farewell to the forests and wild-hanging woods;

Farewell to the torrents and loud-pouring floods.

My heart's in the Highlands, my heart is not here,

My heart's in the Highlands a-chasing the deer;

Chasing the wild deer, and following the roe--

My heart's in the Highlands wherever I go.

Robert Burns's My heart's in the Highlands

Robert Burns, Scotland’s national bard, is celebrated for his ability to distill profound emotion and cultural identity into lyrical verse. His poem "My Heart’s in the Highlands" is a poignant expression of longing, patriotism, and an almost spiritual connection to the Scottish landscape. Written in the late 18th century, the poem resonates with themes of exile, nostalgia, and the unbreakable bond between a person and their homeland. Through its evocative imagery, rhythmic cadence, and emotional depth, Burns crafts a work that transcends its historical moment, speaking to universal human experiences of displacement and yearning.

This essay will explore the poem’s historical and biographical context, its use of literary devices, its thematic concerns, and its enduring emotional impact. By situating the poem within Burns’ broader oeuvre and the Romantic tradition, we can better appreciate its significance as both a personal lament and a cultural artifact.

Historical and Biographical Context

To fully grasp the emotional weight of "My Heart’s in the Highlands," one must consider the political and social climate of Scotland in Burns’ time. The 18th century was a period of profound transformation for Scotland, particularly in the wake of the 1707 Act of Union with England and the failed Jacobite uprisings (notably the crushing defeat at Culloden in 1746). These events led to the suppression of Highland culture, including the banning of tartan and the dismantling of the clan system. The Highlands, once a symbol of fierce independence and ancient traditions, became romanticized in literature as a lost paradise—a motif Burns employs masterfully in this poem.

Burns himself was a Lowlander, hailing from Ayrshire, yet he frequently expressed admiration for Highland culture and landscape. His fascination with the region was not merely aesthetic but deeply political; he sympathized with the Jacobite cause and lamented the erosion of Scottish autonomy. While Burns never lived in the Highlands, his poem captures the collective Scottish nostalgia for a vanishing way of life. The repeated refrain, "My heart’s in the Highlands," suggests an almost physical separation between the speaker’s body and soul, reinforcing the idea that true belonging lies in a place now out of reach.

Literary Devices and Structure

Burns’ poem is deceptively simple in its structure, yet rich in its use of poetic techniques. The poem consists of two stanzas, each reinforcing the central theme of longing through repetition and vivid natural imagery. The lack of a rigid formal structure (such as a sonnet or villanelle) lends the poem a spontaneous, song-like quality, characteristic of Burns’ folk-inspired style.

Repetition and Refrain

The most striking feature of the poem is its insistent repetition:

"My heart’s in the Highlands, my heart is not here;

My heart’s in the Highlands a-chasing the deer."

This refrain acts as an incantation, reinforcing the speaker’s unwavering attachment to the Highlands. The repetition of "farewell" in the second stanza amplifies the sense of loss, as if the speaker is ritually mourning each element of the landscape—mountains, valleys, forests, and torrents. The effect is cumulative, building a crescendo of sorrow and reverence.

Imagery and Symbolism

Burns populates the poem with dynamic natural imagery, painting the Highlands as both idyllic and untamed. The "mountains high cover’d with snow" and the "wild-hanging woods" evoke a sublime landscape, majestic yet perilous. The deer and roe, traditional symbols of freedom and wilderness, become metaphors for the untamed spirit of Scotland itself. The "loud-pouring floods" and "torrents" suggest both the vitality and the uncontrollable force of nature, mirroring the passionate, unrestrained emotions of the speaker.

Rhythm and Musicality

Burns was deeply influenced by Scottish folk music, and this poem reflects that heritage. The trochaic and anapestic rhythms create a galloping cadence, mimicking the chase of the deer. The poem’s musicality would have made it suitable for singing, aligning with Burns’ practice of writing lyrics for traditional tunes. This oral quality ensures that the poem is not just read but felt, its rhythms echoing the heartbeat of the exiled speaker.

Themes and Philosophical Underpinnings

At its core, "My Heart’s in the Highlands" is a meditation on belonging and displacement. The speaker’s physical presence is detached from his emotional and spiritual home, a condition that resonates with anyone who has experienced exile—whether voluntary or enforced. This theme aligns with broader Romantic preoccupations with nature, memory, and the sublime. Like Wordsworth’s "Tintern Abbey," Burns’ poem explores how landscapes shape identity and how memory sustains connection across distance.

Nostalgia and Idealization

The Highlands are depicted not as they were in reality—a region suffering from forced clearances and economic hardship—but as an idealized realm of valor and natural beauty. This idealization is characteristic of Romantic nationalism, where the past is mythologized to serve present emotional needs. The phrase "birth-place of valour, the country of worth" elevates the Highlands to a legendary status, suggesting that the land itself imbues its people with nobility.

The Eternal Return

The circular structure of the poem—beginning and ending with the same refrain—implies that the speaker’s longing is perpetual. No matter where he goes, his heart remains fixed in the Highlands. This cyclical motion reflects a key Romantic belief in the enduring power of memory and the impossibility of true separation from one’s roots.

Comparative Readings

Burns’ poem can be fruitfully compared to other works of Romantic exile and nostalgia. Sir Walter Scott’s "The Lady of the Lake" similarly romanticizes the Highlands, while later poets like W.B. Yeats (in "The Lake Isle of Innisfree") echo Burns’ theme of yearning for an idealized homeland. Even in contemporary literature, the motif of an unreachable paradise persists, demonstrating the timelessness of Burns’ sentiment.

Emotional Impact and Legacy

What makes "My Heart’s in the Highlands" so enduring is its raw emotional honesty. Burns does not merely describe the Highlands; he makes the reader feel the ache of separation. The poem’s universality lies in its ability to speak to anyone who has loved a place deeply—whether a homeland, a childhood landscape, or a lost refuge.

In modern Scotland, Burns’ verse remains a cultural touchstone, often recited at gatherings to evoke national pride. The poem’s themes of resilience and undying attachment resonate in a world where migration and displacement are increasingly common experiences.

Conclusion

Robert Burns’ "My Heart’s in the Highlands" is a masterful blend of personal emotion and cultural memory. Through its hypnotic refrains, vivid imagery, and rhythmic vitality, the poem captures the essence of Romantic longing while rooting it firmly in Scotland’s historical struggles. More than two centuries after its composition, the poem continues to move readers, proving that great poetry transcends time and place. In Burns’ own words, the heart remains where it truly belongs—no matter how far the body may roam.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more