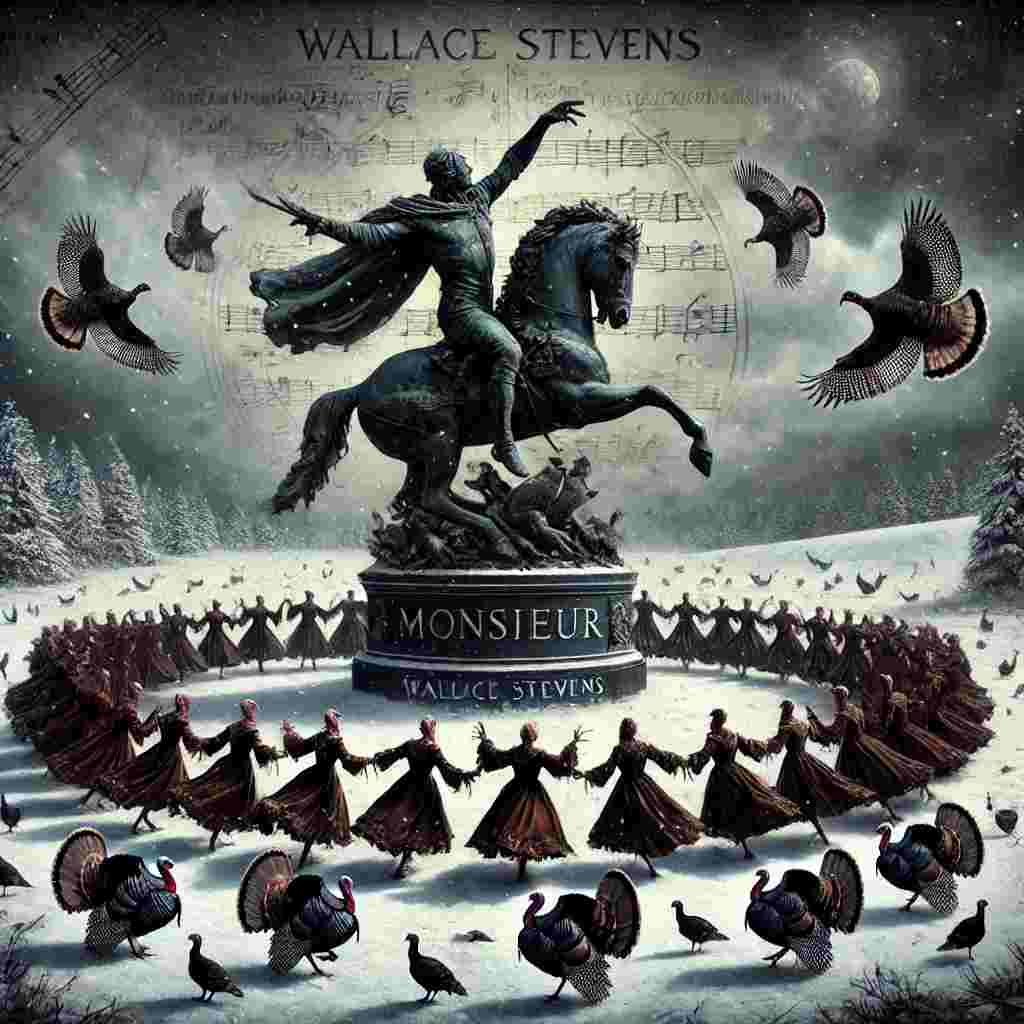

Dance of the Macabre Mice

Wallace Stevens

1879 to 1955

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

In the land of turkeys in turkey weather

At the base of the statue, we go round and round.

What a beautiful history, beautiful surprise!

Monsieur is on horseback. The horse is covered with mice.

This dance has no name. It is a hungry dance.

We dance it out to the tip of Monsieur’s sword,

Reading the lordly language of the inscription,

Which is like zithers and tambourines combined:

The Founder of the State. Whoever founded

A state that was free, in the dead of winter, from mice?

What a beautiful tableau tinted and towering,

The arm of bronze outstretched against all evil!

Wallace Stevens's Dance of the Macabre Mice

Wallace Stevens’ Dance of the Macabre Mice is a subversive meditation on power, memory, and the absurdity of monumental history. Written in 1935 amid global economic collapse and rising authoritarianism, the poem dismantles the mythologies of statecraft through its grotesque carnival of mice swarming a statue of a military hero. Stevens employs surreal imagery, ironic juxtapositions, and metaphysical conceits to challenge the viewer’s passive acceptance of nationalist iconography, revealing how public monuments often codify violence as virtue.

Historical and Cultural Context: Statues in the Age of Disillusionment

The 1930s witnessed both the erosion of democratic ideals and the fetishization of strongman politics, contexts that permeate the poem’s critique. The statue of “The Founder of the State” evokes equestrian monuments to figures like Andrew Jackson or Napoleon-symbols of imperial conquest recast as civilizing heroes3. Stevens subverts this tradition by having mice, traditional emblems of pestilence and decay, “cover” the horse and mock the inscription’s “lordly language”4. This mirrors contemporaneous debates about historical memory; as fascist regimes erected grandiose statues to legitimize their power, Stevens exposes the fragility of such symbols when confronted with organic, anarchic life.

The reference to “turkey weather” situates the poem in a specifically American context of Thanksgiving mythology, where narratives of colonial “founders” often sanitize genocide2. By asking, “Whoever founded / A state that was free, in the dead of winter, from mice?” Stevens highlights the impossibility of pure origins-all states bear the vermin of compromise and violence5.

Literary Devices: Conceits of Power

The poem’s central metaphysical conceit-mice dancing around a bronze sword-transforms a familiar scene into an existential farce. The statue’s “arm of bronze outstretched against all evil” becomes a perch for creatures embodying the “hungry dance” of survival, reducing military glory to a playground for scavengers12. Stevens amplifies this through synesthetic imagery: the inscription sounds like “zithers and tambourines combined,” merging martial pomposity with carnivalesque noise4. This dissonance echoes Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, where beggars and thieves parody societal hierarchies.

Irony permeates the exclamatory tone-“What a beautiful history! Beautiful surprise!”-as the speaker feigns awe while underscoring historical amnesia3. The mice’s nameless dance contrasts with the statue’s explicit labeling as “The Founder,” suggesting that lived experience defies official narratives. Stevens further destabilizes meaning through indeterminate pronouns: “we go round and round” implicates readers in the cycle of unthinking veneration5.

Philosophical Themes: The Death of Heroes

The poem engages with Nietzschean concepts of monumental history, which warns that idolizing past heroes stifles present vitality. The mice’s “hungry dance” embodies the will to power-not through conquest but through persistent erosion. Their consumption of the statue literalizes Walter Benjamin’s maxim that “every monument of civilization is a monument of barbarism”35.

Stevens also critiques binary morality. The sword “against all evil” becomes absurd when wielded by a figure whose legacy sustains the mice’s survival. This aligns with the poet’s broader skepticism toward absolutism, echoed in Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction: “It is possible, possible, possible. It must / Be possible”4. The mice’s anarchic energy suggests that truth emerges not from fixed ideals but from the messy interplay of competing needs.

Emotional Resonance: Laughter as Resistance

Unlike Eliot’s despairing Waste Land, Stevens’ poem finds liberation in absurdity. The mice’s dance evokes both unease and exhilaration-a recognition of shared fragility. Readers may feel complicit when confronted with the “we” participating in this ritual, yet the lack of a named dance creates space for reinterpretation. This emotional duality reflects the 1930s zeitgeist: anxiety over collapsing systems coupled with avant-garde experimentation.

The final tableau’s vivid grotesquerie-“The horse is covered with mice”-resonates with contemporary audiences grappling with fallen monuments. It invites neither nihilism nor nostalgia but a clearsighted acknowledgment that power, like bronze, inevitably oxidizes under the “turkey weather” of time.

Biographical and Comparative Insights

Stevens’ insurance career exposed him to the bureaucratic machinery underpinning societal order, informing his critique of institutional overreach. Like Kafka’s Josef K., his mice confront an incomprehensible authority figure, though with playful defiance rather than terror5. The poem also dialogues with William Carlos Williams’ Paterson, where the Passaic River undermines civic monuments, asserting nature’s indifference to human ambition.

In conclusion, Dance of the Macabre Mice remains urgently relevant in an era of renewed idolatry. By letting vermin overrun the Founder’s sword, Stevens suggests that true freedom lies not in bronze effigies but in the irreducible chaos of life-a lesson as vital now as in the “dead of winter” 193524.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!