Sprightly Old Age

Leigh Hunt

1784 to 1859

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

When the sports of youth I see,

Youth itself returns to me.

Then indeed my old age springs,

To the dance on starting wings.

Stop, Cybele, roses there, —

As befits a dancer's hair:

Grey-beard sloth away be flung;

And I'll join you, young for young,

Afterwards go fetch we wine,

Bounty of a fruit divine;

And I'll show what age can do,

Able still to warble too,

Able still to drink down sadness,

And display a graceful madness.

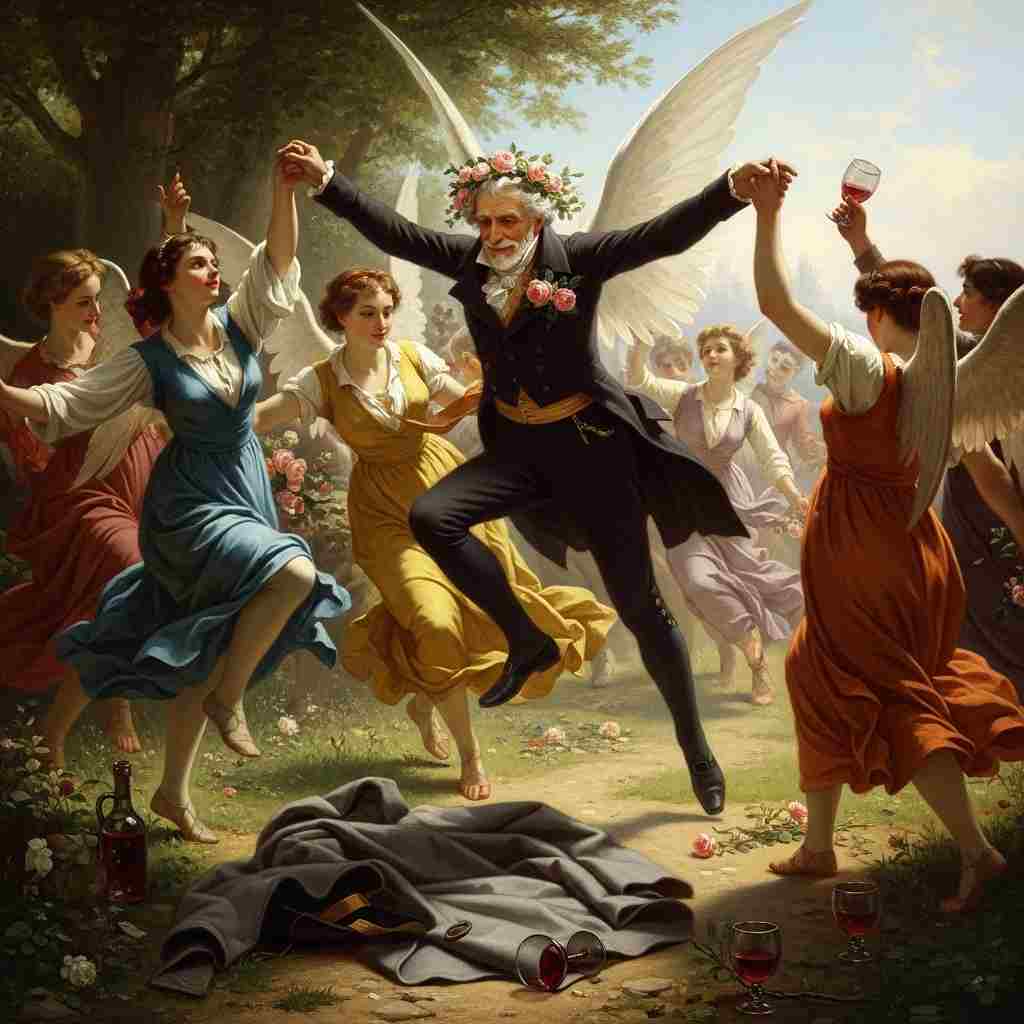

Leigh Hunt's Sprightly Old Age

Leigh Hunt’s "Sprightly Old Age" is a jubilant meditation on the persistence of youthful spirit in the later stages of life. Through vivid imagery, mythological allusions, and a tone of exuberant defiance, Hunt challenges conventional perceptions of aging as a period of decline. Instead, he presents old age as a time of renewed vigor, where the pleasures of youth—dancing, drinking, and joy—remain accessible to those who embrace them. This essay explores the poem’s historical and cultural context, its literary devices, central themes, and emotional resonance, while also considering Hunt’s personal philosophy and possible influences from classical and Romantic traditions.

Historical and Cultural Context

Leigh Hunt (1784–1859) was a central figure in the Romantic literary movement, known for his essays, poetry, and role as an editor who championed the works of Keats and Shelley. Living in an era that prized emotional intensity and individualism, Hunt often infused his work with a sense of optimism and sensuous delight. "Sprightly Old Age" reflects these Romantic ideals, particularly the rejection of societal constraints—including age-related expectations—in favor of personal joy and creative vitality.

The early 19th century, when Hunt was most active, was a period of significant social change, with industrialization altering traditional ways of life. The Romantic movement, in response, often looked to nature, myth, and personal experience as sources of truth and beauty. Hunt’s poem aligns with this sensibility, celebrating the timelessness of human joy rather than succumbing to the era’s growing emphasis on productivity and utilitarian values.

Additionally, the poem’s classical allusions (such as the reference to Cybele) suggest Hunt’s engagement with antiquity, a common feature among Romantic writers who sought to reconnect with older, more organic forms of culture. The poem’s defiance of age-related decline also echoes the carpe diem tradition, though with a twist: rather than urging youth to seize the day, Hunt insists that the elderly can still seize it for themselves.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Hunt employs a range of literary devices to convey his celebration of enduring vitality. The poem’s imagery is particularly striking, blending mythological references with sensory details to create a vivid, almost intoxicating atmosphere.

Mythological Allusion: Cybele and the Roses

The invocation of "Stop, Cybele, roses there, — / As befits a dancer's hair" introduces a classical dimension to the poem. Cybele, the Phrygian mother goddess associated with nature and wild abandon, was often depicted with a crown of roses. By addressing her, Hunt aligns his speaker with a figure of untamed energy, reinforcing the idea that age need not mean restraint. The roses, traditional symbols of beauty and ephemerality, are not just decorative but emblematic of life’s fleeting pleasures—pleasures the speaker insists are still within reach.

Kinetic Imagery and Movement

The poem is suffused with motion: "the dance on starting wings," "Grey-beard sloth away be flung," and the implicit movement of drinking and singing all contribute to a sense of dynamic energy. The phrase "starting wings" suggests sudden, almost avian lightness, reinforcing the idea that the speaker’s old age is not a burden but a state of liberation. The rejection of "grey-beard sloth" is particularly defiant, positioning lethargy as an enemy to be cast aside rather than an inevitable companion of aging.

Sensory Appeal: Wine and Song

The references to wine ("Bounty of a fruit divine") and song ("Able still to warble too") engage multiple senses, grounding the poem’s abstract joy in tangible experiences. Wine, a longstanding symbol of conviviality and divine inspiration (from Dionysian rites to Romantic excess), becomes a metaphor for life’s richness. The speaker’s assertion that he can "drink down sadness" suggests not mere escapism but an active, almost alchemical transformation of sorrow into joy.

Paradox and Defiance

The poem thrives on paradox: old age is not a withering but a "sprightly" resurgence. The phrase "young for young" encapsulates this idea perfectly—the speaker does not merely observe youth but matches it in energy. The closing lines ("Able still to drink down sadness, / And display a graceful madness") further this defiance, presenting madness not as decline but as a form of liberation, a "graceful" refusal to conform to societal expectations of dignified old age.

Themes

The Persistence of Youthful Spirit

The central theme of "Sprightly Old Age" is the undiminished capacity for joy, regardless of chronological age. The speaker does not merely reminisce about youth but actively rekindles it, declaring that "Youth itself returns to me." This is not nostalgia but reclamation, suggesting that the essence of youth—vitality, spontaneity, pleasure—is not bound by time.

Defiance of Age-Related Stereotypes

Hunt challenges the cultural narrative that equates aging with decline. The casting off of "grey-beard sloth" is an explicit rejection of the passive, weary old man trope. Instead, the speaker embraces movement, music, and merriment, insisting that age can be as dynamic as youth.

The Transformative Power of Joy

The poem suggests that joy is not just an emotion but an act of resistance. By "drink[ing] down sadness" and displaying "graceful madness," the speaker demonstrates how deliberate engagement with pleasure can counteract life’s inevitable sorrows. This aligns with Romanticism’s emphasis on the individual’s power to shape their own emotional reality.

Emotional Impact and Philosophical Underpinnings

The poem’s emotional resonance lies in its infectious exuberance. Unlike meditations on aging that dwell on loss (such as Yeats’ "Sailing to Byzantium"), Hunt’s work is a rallying cry, urging the reader to reject resignation. The speaker’s tone is not wistful but triumphant, making the poem feel less like an elegy and more like a manifesto for living fully at any age.

Philosophically, the poem echoes Epicurean ideals—the pursuit of pleasure as a means of attaining ataraxia (freedom from distress). However, it also carries a Dionysian spirit, embracing not just moderate enjoyment but ecstatic abandon. The "graceful madness" at the poem’s close suggests that true vitality requires a willingness to defy convention, even in old age.

Comparative Analysis

Hunt’s poem can be fruitfully compared to other works that address aging and vitality.

-

Wordsworth’s "Ode: Intimations of Immortality": While Wordsworth laments the loss of childhood’s "visionary gleam," Hunt’s speaker claims to recapture it actively. Both poems engage with memory and renewal, but Hunt’s is more celebratory and less elegiac.

-

Yeats’ "An Acre of Grass": Yeats’ late poem also yearns for "frenzy" in old age, but his tone is more desperate, whereas Hunt’s is effortlessly joyful.

-

Classical precedents (Horace, Anacreon): The carpe diem tradition often urged the young to enjoy life before decline. Hunt subverts this by extending the invitation to the elderly.

Biographical Insights

Hunt’s personal life informs the poem’s tone. Despite financial struggles, political persecution (he was jailed for criticizing the Prince Regent), and health issues, Hunt maintained a reputation for cheerfulness. His letters and essays frequently emphasize the importance of finding joy in small pleasures, a philosophy embodied in "Sprightly Old Age." The poem can thus be read as both a personal credo and a public encouragement to others.

Conclusion

"Sprightly Old Age" is a masterful assertion of joy’s timelessness. Through its mythological allusions, kinetic imagery, and defiant tone, Hunt crafts a vision of aging that is not about loss but about continued engagement with life’s delights. The poem’s emotional power lies in its refusal to accept decline as inevitable, offering instead a model of graceful exuberance. In an era that often associates aging with irrelevance, Hunt’s work remains a vital reminder that the human spirit need not wither with time—it can, instead, dance on "starting wings."

By celebrating the persistence of youthful vitality, Hunt not only challenges societal norms but also invites readers of all ages to embrace a life of passion, pleasure, and "graceful madness." In doing so, he ensures that "Sprightly Old Age" resonates as strongly today as it did in the Romantic era.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more