The African Chief

William Cullen Bryant

1794 to 1878

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

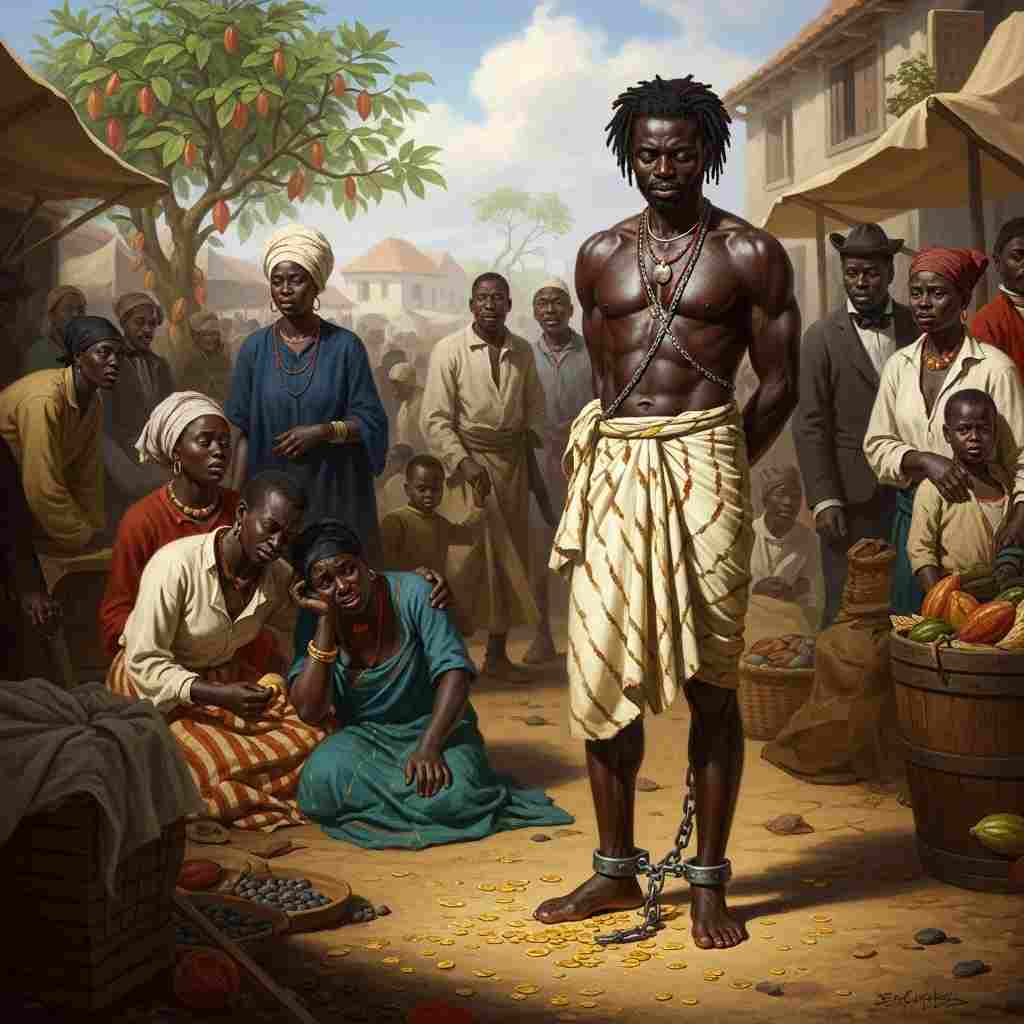

Chained in the market-place he stood,

A man of giant frame,

Amid the gathering multitude

That shrunk to hear his name—

All stern of look and strong of limb,

His dark eye on the ground:—

And silently they gazed on him,

As on a lion bound.

Vainly, but well, that chief had fought,

He was a captive now,

Yet pride, that fortune humbles not,

Was written on his brow.

The scars his dark broad bosom wore,

Showed warrior true and brave;

A prince among his tribe before,

He could not be a slave.

Then to his conqueror he spake—

"My brother is a king;

Undo this necklace from my neck,

And take this bracelet ring,

And send me where my brother reigns,

And I will fill thy hands

With store of ivory from the plains,

And gold-dust from the sands."

"Not for thy ivory nor thy gold

Will I unbind thy chain;

That bloody hand shall never hold

The battle-spear again.

A price thy nation never gave

Shall yet be paid for thee;

For thou shalt be the Christian's slave,

In lands beyond the sea."

Then wept the warrior chief, and bade

To shred his locks away;

And one by one, each heavy braid

Before the victor lay.

Thick were the platted locks, and long,

And closely hidden there

Shone many a wedge of gold among

The dark and crisped hair.

"Look, feast thy greedy eye with gold

Long kept for sorest need:

Take it—thou askest sums untold,

And say that I am freed.

Take it—my wife, the long, long day,

Weeps by the cocoa-tree,

And my young children leave their play,

And ask in vain for me."

"I take thy gold—but I have made

Thy fetters fast and strong,

And ween that by the cocoa shade

Thy wife will wait thee long."

Strong was the agony that shook

The captive's frame to hear,

And the proud meaning of his look

Was changed to mortal fear.

His heart was broken—crazed his brain:

At once his eye grew wild;

He struggled fiercely with his chain,

Whispered, and wept, and smiled;

Yet wore not long those fatal bands,

And once, at shut of day,

They drew him forth upon the sands,

The foul hyena's prey.

William Cullen Bryant's The African Chief

William Cullen Bryant’s The African Chief is a powerful and haunting poem that confronts the brutality of slavery, the erasure of identity, and the psychological torment of captivity. Written in the early 19th century, the poem engages with the transatlantic slave trade, a subject that was both politically charged and morally urgent during Bryant’s lifetime. Through vivid imagery, stark contrasts, and emotional intensity, Bryant crafts a narrative that is as much a lament for lost freedom as it is an indictment of colonial oppression. This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional resonance, while also considering its place within Bryant’s broader body of work and the abolitionist discourse of the time.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate The African Chief, one must situate it within the early 19th-century American literary landscape, a period marked by growing abolitionist sentiment and heated debates over slavery. Bryant, though primarily known as a nature poet and journalist, was also an outspoken critic of slavery, and this poem reflects his moral outrage. The transatlantic slave trade had been officially abolished in the United States in 1808, yet the domestic slave trade persisted, and the forced migration of African people to the Americas remained a brutal reality.

The poem’s depiction of an African warrior reduced to chains would have resonated with contemporary readers who were familiar with accounts of enslaved individuals—many of whom were captured in warfare or raids—being transported across the Atlantic. The chief’s nobility and martial prowess contrast sharply with his degradation, reinforcing the inhumanity of slavery. Bryant’s portrayal aligns with abolitionist rhetoric that emphasized the dignity of African people and the moral bankruptcy of their enslavers.

Additionally, the reference to Christianity in the conqueror’s speech ("For thou shalt be the Christian's slave") is deeply ironic, critiquing the hypocrisy of a religion that preached love and brotherhood while sanctioning human bondage. This critique was common in abolitionist literature, which often highlighted the contradiction between Christian ethics and the realities of slavery.

Literary Devices and Structure

Bryant employs a range of literary techniques to heighten the poem’s emotional and thematic impact.

Imagery and Symbolism

The poem is rich in visual and tactile imagery, immersing the reader in the chief’s suffering. His "giant frame" and "dark broad bosom" suggest physical strength and nobility, while his scars testify to his valor. These descriptions establish him as a figure of dignity, making his enslavement all the more tragic. The "lion bound" simile in the opening stanza reinforces his regal nature while foreshadowing his helplessness.

Gold, both literal and symbolic, plays a crucial role. The chief’s braids contain "many a wedge of gold," representing not just material wealth but cultural identity. The forced removal of his hair—a humiliating act often used to strip enslaved people of their heritage—symbolizes the erasure of his past. His offer of gold in exchange for freedom underscores his desperation, but the conqueror’s refusal reveals the irredeemable greed and cruelty of the slavers.

Contrast and Irony

Bryant repeatedly juxtaposes strength with subjugation, pride with degradation. The chief, once a "prince among his tribe," is now a commodity in the marketplace. His initial defiance ("pride, that fortune humbles not") gives way to "mortal fear," illustrating the psychological destruction wrought by slavery. The conqueror’s cold dismissal of the chief’s pleas ("I take thy gold—but I have made / Thy fetters fast and strong") is a masterstroke of dramatic irony, as the reader recognizes the futility of the chief’s bargaining.

Dialogue and Voice

The poem’s dialogue heightens its emotional immediacy. The chief’s speech is dignified and diplomatic, appealing to kinship ("My brother is a king") and offering material wealth. His conqueror, by contrast, speaks with chilling finality, reducing the chief’s humanity to economic value. The shift from the chief’s proud bearing to his broken, crazed state is rendered through fragmented actions—"Whispered, and wept, and smiled"—a technique that conveys mental collapse without explicit commentary.

Themes

The Dehumanization of Slavery

The central theme of The African Chief is the systematic dehumanization inherent in slavery. The chief is stripped of his identity, his freedom, and ultimately his sanity. His reduction from warrior to prey—"the foul hyena’s prey"—underscores the animalistic brutality of his fate. Bryant does not shy away from depicting the full horror of this transformation, forcing the reader to confront the human cost of slavery.

The Corruption of Power and Greed

The conqueror’s refusal to accept the chief’s gold—despite its obvious value—reveals a deeper, more insidious motive: the desire not for wealth but for domination. The chief’s gold is meaningless compared to the power derived from his enslavement. This reflects the broader economic and psychological mechanisms of slavery, where human beings were commodified not merely for labor but as symbols of conquest.

The Futility of Resistance

The chief’s resistance, both physical and verbal, is ultimately futile. His strength, his bargaining, and even his emotional breakdown cannot alter his fate. This bleak conclusion serves as a commentary on the overwhelming machinery of the slave trade, which crushed individual agency on a massive scale.

Emotional Impact and Philosophical Undercurrents

The poem’s emotional power lies in its unflinching portrayal of despair. The chief’s weeping, his mention of his waiting wife and children, and his final descent into madness evoke profound pathos. Bryant does not offer redemption or hope—only the stark reality of suffering. This aligns with Romanticism’s preoccupation with tragedy and the sublime, where extreme emotional states reveal deeper truths about the human condition.

Philosophically, the poem raises questions about freedom, dignity, and the limits of endurance. The chief’s broken mind suggests that some forms of suffering are so profound that they transcend physical pain, annihilating the self. This idea resonates with later existential and trauma literature, which explores how extreme oppression can fracture identity.

Comparative Analysis and Biographical Insights

Bryant’s poem can be compared to other abolitionist works of the period, such as John Greenleaf Whittier’s The Slave Ships or Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Slave’s Dream. Like these poems, The African Chief personalizes the victim of slavery, giving him a voice and a history. However, Bryant’s poem is particularly notable for its psychological depth—the chief’s madness is a more extreme depiction of trauma than many contemporaneous works dared to portray.

Biographically, Bryant’s own views on slavery evolved over time. While he was never as radical as some abolitionists, his journalism and poetry reflect a consistent opposition to slavery. The African Chief may have been influenced by his readings of African travel narratives or firsthand accounts of the slave trade, which were increasingly circulated in abolitionist circles.

Conclusion

The African Chief is a searing indictment of slavery, rendered with emotional precision and moral urgency. Through its vivid imagery, stark contrasts, and unrelenting tragedy, the poem forces the reader to witness the destruction of a noble individual at the hands of an indifferent system. Bryant’s work stands as both a historical document of abolitionist sentiment and a timeless meditation on the cost of human cruelty. Its power lies not in hopeful resolution, but in its refusal to look away from suffering—a refusal that remains as necessary today as it was in Bryant’s time.

In engaging with this poem, we are reminded of poetry’s capacity to bear witness, to evoke empathy, and to challenge injustice. Bryant may not offer solutions, but by giving voice to the African chief’s anguish, he ensures that his story—and the stories of countless others—is not forgotten.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more