Virtue

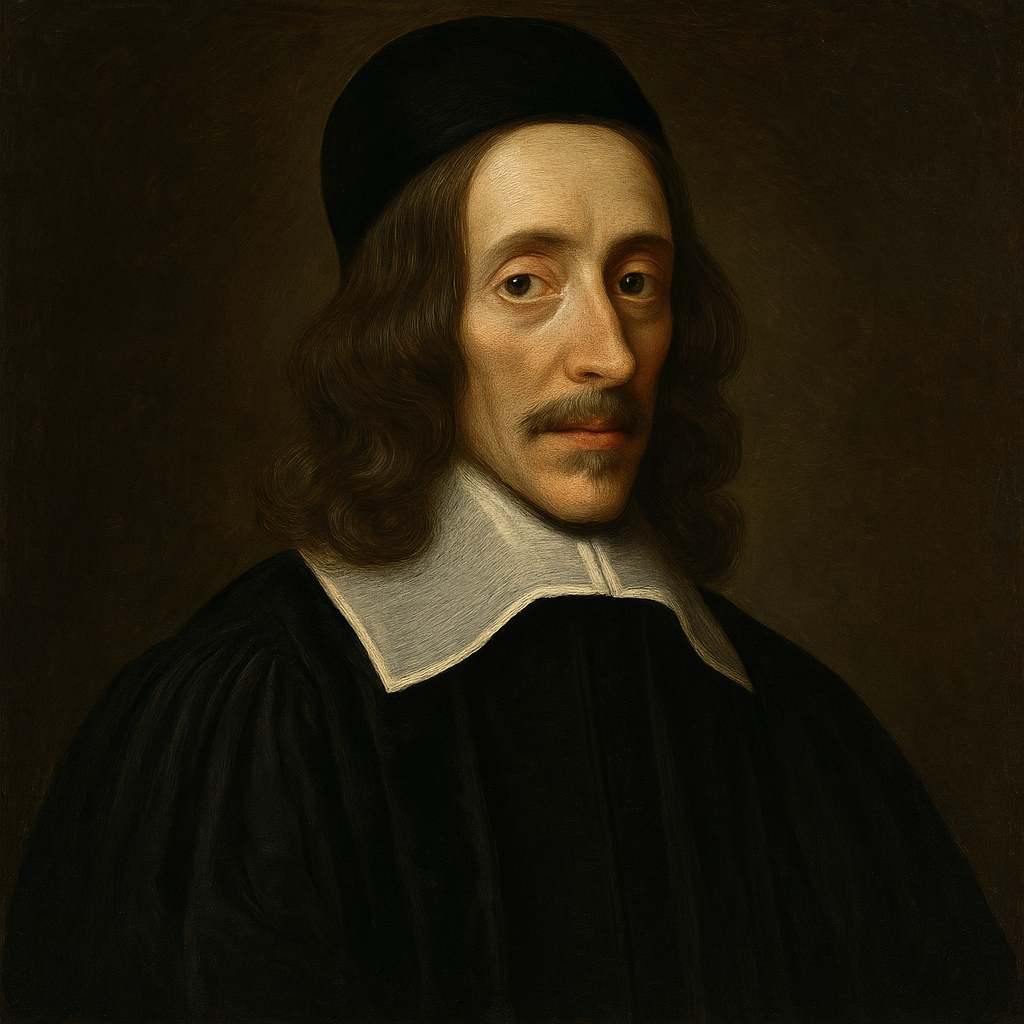

George Herbert

1593 to 1633

Sweet day, so cool, so calm, so bright,

The bridal of the earth and sky:

The dew shall weep thy fall to-night;

For thou must die.

Sweet rose, whose hue angry and brave

Bids the rash gazer wipe his eye:

Thy root is ever in its grave,

And thou must die.

Sweet spring, full of sweet days and roses,

A box where sweets compacted lie;

My music shows ye have your closes,

And all must die.

Only a sweet and virtuous soul,

Like season'd timber, never gives;

But though the whole world turn to coal,

Then chiefly lives.

George Herbert's Virtue

Introduction

George Herbert's "Virtue" stands as one of the finest examples of metaphysical poetry from the 17th century, embodying the movement's characteristic fusion of intellectual rigor with emotional depth. Through its masterful employment of extended metaphor, structural precision, and theological undertones, the poem crystallizes Herbert's broader preoccupation with the transience of worldly beauty and the endurance of spiritual virtue. This analysis will examine how Herbert crafts a sophisticated argument about mortality and immortality through careful poetic devices, biblical allusions, and a progressive series of natural images that culminate in a profound spiritual truth.

Structure and Form

The poem's architectural precision cannot be overlooked. Herbert employs four quatrains, each following a consistent rhyme scheme (AABB), with the first three stanzas sharing a parallel structure that ends with the memento mori refrain "must die." This repetition creates a rhythmic inevitability that mirrors the poem's thematic concern with mortality. The fourth stanza's deviation from this pattern, where "gives" and "lives" replace the expected death-oriented conclusion, serves as both structural and philosophical pivot.

Each stanza's third line is indented, creating a visual pause before the stark final line. This typographical choice reflects Herbert's training as a priest and his understanding of liturgical rhythm – the space operates like a breath before a sermon's crucial point. The shorter final lines ("For thou must die" and its variations) function as both epitaph and epiphany, their brevity emphasizing their weight.

Nature as Divine Text

Herbert's selection of natural imagery follows the metaphysical tradition of reading nature as God's second book. The progression from "day" to "rose" to "spring" represents an expanding scope of temporal existence, each image more encompassing than the last. The "sweet day" introduces immediacy and specificity, while the "sweet rose" represents individual beauty, and "sweet spring" encompasses an entire season of renewal.

The opening metaphor of the day as "The bridal of the earth and sky" recalls both classical and Christian traditions. The marriage imagery suggests both fertility and unity, while simultaneously evoking the biblical notion of Christ as bridegroom to the Church. This dual reading exemplifies Herbert's characteristic ability to layer secular and sacred meanings.

The Paradox of Beauty

Herbert's treatment of beauty is particularly nuanced. The rose's "hue angry and brave" presents a startling juxtaposition – beauty that possesses both aggression and courage. The phrase "Bids the rash gazer wipe his eye" suggests multiple readings: the viewer might be moved to tears, dazzled to the point of physical reaction, or forced to reconsider their hasty judgment. This complexity characterizes Herbert's approach to sensual beauty as both alluring and potentially dangerous to spiritual development.

Musical and Theological Resonance

The musical metaphor in the third stanza ("My music shows ye have your closes") demonstrates Herbert's sophisticated understanding of both musical theory and theological doctrine. As a skilled lutenist, Herbert would have understood "closes" as musical cadences or endings, but the term also carries eschatological weight, suggesting the closure of earthly existence. This double meaning exemplifies the metaphysical poets' delight in finding spiritual significance in technical vocabulary.

Timber and Transformation

The final stanza's shift to "season'd timber" as a metaphor for the virtuous soul represents the poem's philosophical culmination. The choice of timber is significant – unlike the previous natural images, timber is nature transformed by human intervention, suggesting the role of discipline and preparation in spiritual development. The image carries echoes of Noah's ark (built of gopher wood) and the cross itself, both biblical instances where timber serves as an instrument of salvation.

The Apocalyptic Vision

Herbert's closing image of the world turning to coal presents a startling apocalyptic vision that simultaneously looks forward to Final Judgment while maintaining scientific accuracy – coal being the natural end result of timber under pressure. The paradox that the virtuous soul "Then chiefly lives" when all else is destroyed presents spiritual endurance not as mere survival but as a kind of triumph, suggesting that virtue finds its fullest expression precisely when worldly beauty fails.

Language and Sound

The poem's sonic texture deserves close attention. The repetition of "sweet" (appearing six times) creates a honeyed atmosphere that contrasts with the stark reality of mortality. The alliteration in phrases like "sweet spring" and "season'd timber" provides melodic coherence, while the hard consonants in "coal" and "gives" create moments of sonic tension that reinforce thematic concerns.

Biblical and Literary Context

Herbert's poem engages with several biblical texts, most notably Ecclesiastes' meditation on vanity and the transience of earthly pleasures. The poem's structure mirrors the biblical pattern of wisdom literature, moving from natural observation to spiritual truth. The influence of contemporary writers, particularly John Donne's Holy Sonnets, is evident in the poem's argumentative structure and its fusion of the sacred and secular.

Conclusion

"Virtue" demonstrates Herbert's mastery of the metaphysical style while transcending mere technical virtuosity. The poem's success lies in its ability to make abstract theological concepts tangible through carefully chosen natural imagery, while maintaining an emotional resonance that speaks to universal human experiences of beauty and mortality. Through its brilliant structural design, sophisticated use of metaphor, and theological depth, the poem achieves what it describes – a lasting testament to spiritual endurance amid temporal decay. Herbert's genius lies in creating a work that performs its own argument, becoming itself a kind of "sweet and virtuous soul" that continues to live and illuminate despite the centuries that have passed since its creation.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!