Requiem

Robert Louis Stevenson

1850 to 1894

Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

Robert Louis Stevenson's Requiem

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Requiem is a deceptively simple poem that belies a profound meditation on life, death, and the human yearning for peace. Composed in 1880, the poem reflects Stevenson’s lifelong struggle with illness and his philosophical acceptance of mortality. At just eight lines, Requiem is a masterclass in economy of language, using vivid imagery, rhythmic precision, and universal themes to create a work that resonates deeply with readers across time and culture. This essay will explore the poem’s historical context, its use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional impact, offering a nuanced understanding of its enduring appeal.

Historical and Biographical Context

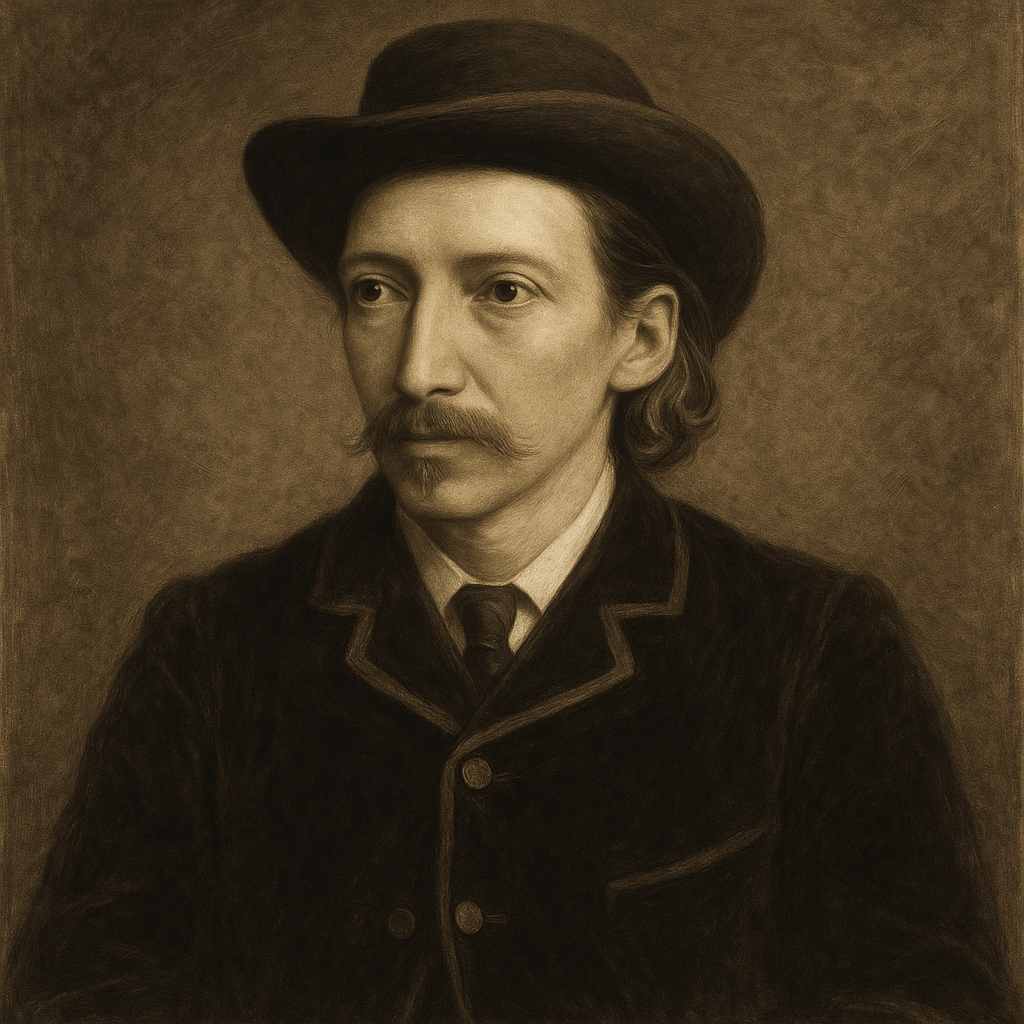

To fully appreciate Requiem, it is essential to consider the life of its author. Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894) was a Scottish novelist, poet, and essayist, best known for works such as Treasure Island, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and Kidnapped. Stevenson suffered from chronic respiratory illness, likely tuberculosis, which plagued him throughout his life and necessitated frequent travels in search of healthier climates. His fragile health imbued him with a keen awareness of mortality, a theme that permeates much of his writing.

Requiem was written during a period of personal reflection and physical decline. By 1880, Stevenson had already endured numerous brushes with death, and his travels had taken him far from his native Scotland. The poem can be seen as both a personal epitaph and a universal meditation on the inevitability of death. Its composition coincided with Stevenson’s growing interest in existential questions, influenced by his reading of philosophers such as Montaigne and his own experiences of suffering and resilience.

The poem’s title, Requiem, is significant. A requiem is traditionally a Mass for the dead in the Catholic tradition, but it also refers to any musical or literary composition honoring the deceased. By titling his poem Requiem, Stevenson situates it within a long tradition of artistic meditations on mortality, inviting readers to consider the poem as both a personal statement and a universal reflection on the human condition.

Structure and Literary Devices

At first glance, Requiem appears straightforward, but its simplicity is carefully crafted. The poem consists of two quatrains, each with an ABAB rhyme scheme. This structure lends the poem a sense of balance and closure, mirroring the themes of finality and resolution. The meter is predominantly iambic, with alternating lines of tetrameter and trimeter, creating a rhythmic cadence that evokes the solemnity of a funeral march.

Stevenson’s use of imagery is particularly striking. The opening line, “Under the wide and starry sky,” immediately situates the reader in a vast, almost cosmic setting. The juxtaposition of “wide” and “starry” suggests both the infinite expanse of the universe and the intimate beauty of the night sky. This imagery serves to contextualize the speaker’s death within the broader tapestry of existence, emphasizing its naturalness and inevitability.

The second line, “Dig the grave and let me lie,” is direct and unflinching, reflecting the speaker’s acceptance of death. The imperative tone conveys a sense of agency and resolve, as though the speaker is not merely submitting to death but actively embracing it. This line also introduces the poem’s central metaphor of death as a return home, a theme that is developed in the subsequent lines.

The third and fourth lines, “Glad did I live and gladly die, / And I laid me down with a will,” encapsulate the poem’s philosophical outlook. The repetition of “glad” underscores the speaker’s contentment with both life and death, while the phrase “with a will” suggests a deliberate and purposeful acceptance of mortality. This attitude aligns with Stevenson’s own stoic philosophy, as expressed in his essays and letters.

The second quatrain shifts from the speaker’s personal reflections to a broader, more universal perspective. The line “This be the verse you grave for me” introduces the idea of the poem as an epitaph, a final statement to be inscribed on the speaker’s tombstone. The use of the word “grave” as a verb is a clever pun, linking the act of engraving with the concept of burial.

The final three lines, “Here he lies where he longed to be; / Home is the sailor, home from sea, / And the hunter home from the hill,” are among the most celebrated in English literature. The metaphor of death as a homecoming is both poignant and comforting, suggesting that death is not an end but a return to a state of rest and belonging. The imagery of the sailor and the hunter evokes a sense of completion and fulfillment, as though their journeys—both literal and metaphorical—have reached their natural conclusion.

Themes and Philosophical Underpinnings

Requiem explores several interconnected themes, including mortality, acceptance, and the idea of home. The poem’s treatment of death is neither fearful nor mournful but rather serene and accepting. This reflects Stevenson’s own attitude toward his illness, as well as his broader philosophical outlook. In his essay Aes Triplex, Stevenson writes, “To be deeply interested in the accidents of our existence, to enjoy keenly the mixed texture of human experience, rather leads a man to disregard precautions and risk his life.” This sentiment is echoed in Requiem, where the speaker’s gladness in life and death suggests a life lived fully and without regret.

The theme of home is central to the poem’s emotional resonance. For Stevenson, who spent much of his life traveling in search of health, the concept of home was both literal and metaphorical. In Requiem, home becomes a symbol of peace and finality, a place where the soul can rest after the trials of life. The imagery of the sailor and the hunter returning home reinforces this idea, suggesting that death is not a loss but a reunion.

The poem also touches on the theme of legacy. By framing the poem as an epitaph, Stevenson invites readers to consider how they wish to be remembered. The speaker’s request for a simple verse reflects a desire for authenticity and honesty, qualities that Stevenson valued highly. This theme resonates with readers on a personal level, encouraging them to reflect on their own lives and the mark they wish to leave on the world.

Emotional Impact and Universal Appeal

One of the reasons Requiem has endured as a beloved poem is its ability to connect with readers on an emotional level. Its themes of acceptance and homecoming offer comfort to those grappling with loss or their own mortality. The poem’s serene tone and vivid imagery create a sense of peace and closure, making it a popular choice for funerals and memorials.

The universality of the poem’s themes ensures its relevance across cultures and time periods. The idea of death as a homecoming is a recurring motif in literature and religion, from the ancient Greek concept of Elysium to the Christian notion of heaven. By tapping into this universal archetype, Stevenson creates a poem that speaks to the shared human experience.

The poem’s emotional impact is also heightened by its musicality. The rhythmic cadence and rhyme scheme give the poem a lyrical quality, making it easy to memorize and recite. This musicality enhances its suitability as a requiem, evoking the solemn beauty of a funeral hymn.

Stevenson's Epitaph

The lines from Robert Louis Stevenson's Requiem—

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill—

are inscribed on his gravestone. Stevenson died on December 3, 1894, in Vailima, Samoa, where he had spent the last years of his life. His grave is located atop Mount Vaea, overlooking the Pacific Ocean, a site he had chosen himself. The epitaph, drawn from his own poem, reflects his acceptance of death as a peaceful homecoming and serves as a fitting tribute to his life and legacy.

The inscription captures the essence of Stevenson's philosophy and his longing for rest after a life marked by illness, travel, and creative endeavor. The imagery of the sailor returning from sea and the hunter coming home from the hill evokes a sense of completion and fulfillment, suggesting that Stevenson had found his final resting place in Samoa, a land he had come to love deeply.

The choice of these lines for his epitaph underscores the enduring power of Requiem as both a personal and universal statement about life, death, and the human desire for peace. It also highlights Stevenson's ability to distill profound truths into simple, evocative language, a skill that has ensured his place as one of literature's most beloved figures.

Conclusion

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Requiem is a masterpiece of concision and depth, using simple language and vivid imagery to explore profound themes of mortality, acceptance, and home. Its historical and biographical context enriches our understanding of the poem, revealing it as both a personal statement and a universal meditation on the human condition. Through its careful use of literary devices and its serene, philosophical tone, the poem offers comfort and insight to readers of all backgrounds.

In its eight lines, Requiem captures the essence of Stevenson’s worldview: a life lived with joy and purpose, and a death faced with courage and acceptance. Its enduring appeal lies in its ability to speak to the universal human experience, offering solace and inspiration to those who encounter it. As both a work of art and a philosophical statement, Requiem stands as a testament to the power of poetry to connect us with the deepest truths of our existence.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!