I Have Wandered to a Spring

Edna Wahlert McCourt

1887 to 1963

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

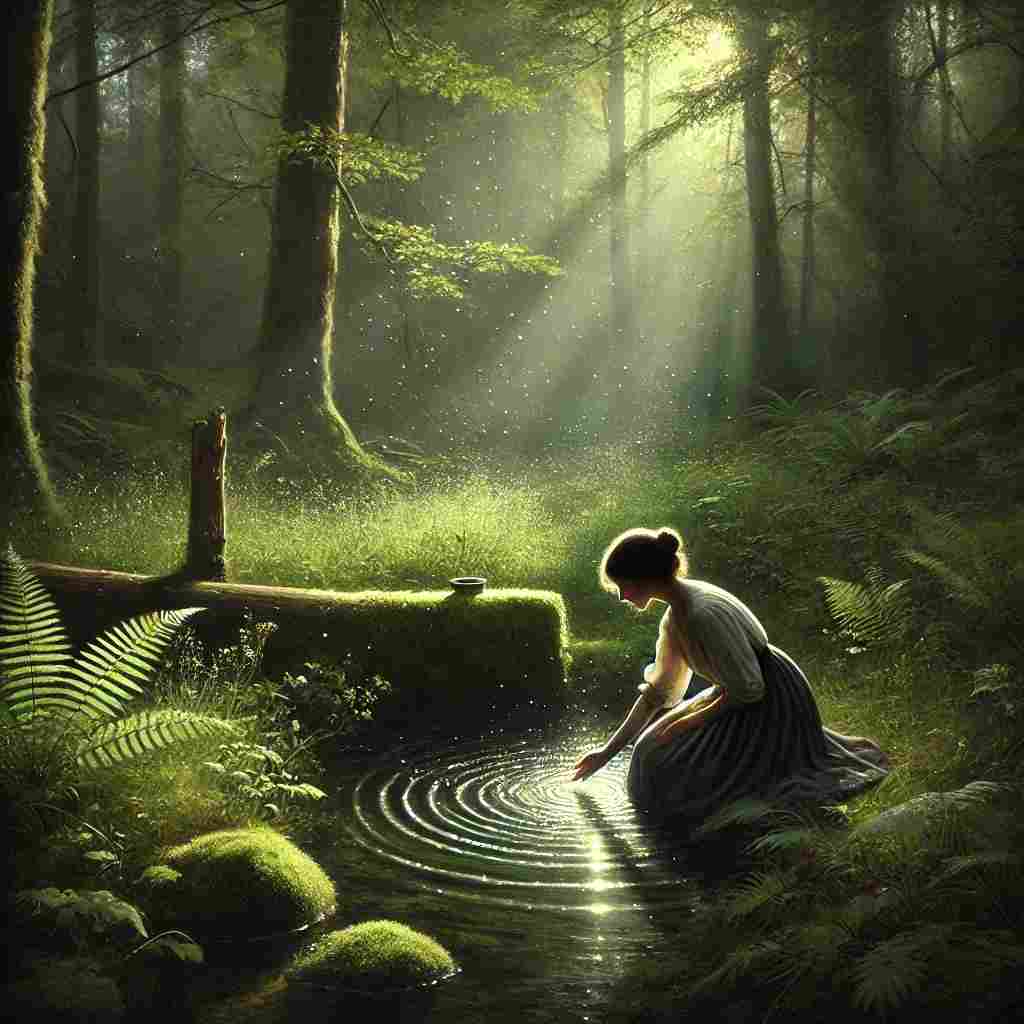

I have wandered to a spring in the forest green and dim,

The sweet quiet stirs about me—

The water twinkles at me,

As I stoop to dip my cup,

As I stoop to drink—to him.

True, I’m only half in earnest—I touch the cool, wet brim—

He’d laugh if he could see me—

I’m glad he doesn’t see me,

As alone with my queer gladness,

I stoop to drink—to him.

Edna Wahlert McCourt's I Have Wandered to a Spring

Edna Wahlert McCourt's poem "I Have Wandered to a Spring" delves into the complex interplay between nature, memory, and personal reflection. Using the symbolic act of drinking from a spring, McCourt reflects on the private, almost sacred act of remembering a loved one. Her poetic language is subtle yet profound, creating a space where the natural environment becomes intertwined with personal reverie. Through its careful phrasing and tone, the poem evokes themes of solitude, memory, and the bittersweet nature of connection.

Analysis

The poem is structured as a monologue, a single speaker in conversation with herself as she addresses an unnamed "him." This ambiguity around the identity of "him" allows for broader interpretations: he could be a lost loved one, a distant romantic figure, or even a representation of memory itself. The use of the spring as a focal point gives the poem a natural setting that suggests purity, renewal, and contemplation.

Opening Lines and Natural Imagery

“I have wandered to a spring in the forest green and dim,

The sweet quiet stirs about me—”

In these lines, the speaker introduces us to the setting: a secluded, tranquil spring within a dimly lit forest. The phrase “forest green and dim” evokes a mood of quietude and intimacy, creating a sense of place where nature serves as both sanctuary and a mirror for inner emotion. The “sweet quiet” suggests that the natural world possesses a comforting quality, and the verb “stirs” subtly brings the scene to life, as if this quietude is almost communicative.

“The water twinkles at me,

As I stoop to dip my cup,

As I stoop to drink—to him.”

Here, the personification of the water “twinkling” conveys a sense of the water as an active participant in the speaker's quiet ritual, reinforcing the intimacy of her connection to the moment and to "him." The act of drinking, however, is both literal and symbolic; bending to the water feels like a kind of homage or offering, suggesting that this act is done in reverence or remembrance.

Tone of Playfulness and Sincerity

“True, I’m only half in earnest—I touch the cool, wet brim—

He’d laugh if he could see me—”

These lines introduce a touch of irony or playfulness. The phrase “half in earnest” implies that while the speaker partakes in this ritual with genuine feeling, she is also aware of its perhaps overly sentimental nature. Imagining his laughter if he could witness her actions injects a light-hearted self-awareness that tempers the earnestness of her gesture. This line creates a complex emotional tone, combining wistfulness, slight embarrassment, and a bittersweet recognition of her own vulnerability.

Private Gladness and Resolution

“I’m glad he doesn’t see me,

As alone with my queer gladness,

I stoop to drink—to him.”

The final stanza solidifies the introspective nature of this poem. The speaker’s gladness is described as “queer,” an adjective that emphasizes the uniqueness and possible incongruity of her joy. This is a happiness tinged with strangeness—perhaps a joy that feels out of place in the context of loss or separation. The repetition of “I stoop to drink—to him” emphasizes that, despite any self-consciousness, this act is meaningful. It is a private moment of communion, connecting her to a person now absent but still profoundly present in her heart.

Conclusion

McCourt’s poem explores the nuances of memory and solitude within a natural setting, using the spring as a metaphorical vessel for both sustenance and reflection. The restrained language, coupled with the private act of drinking to an absent "him," encapsulates the tension between memory and the present moment. The speaker’s mingled emotions—playfulness, self-awareness, and “queer gladness”—reveal the ways in which human experience often sits on the edge of joy and melancholy, particularly in the presence of memory. Thus, "I Have Wandered to a Spring" presents a meditation on the ways we carry loved ones with us, finding solace in small, ritualistic acts that keep the past alive within the present.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!