Sunrise

Charles Tennyson Turner

1808 to 1879

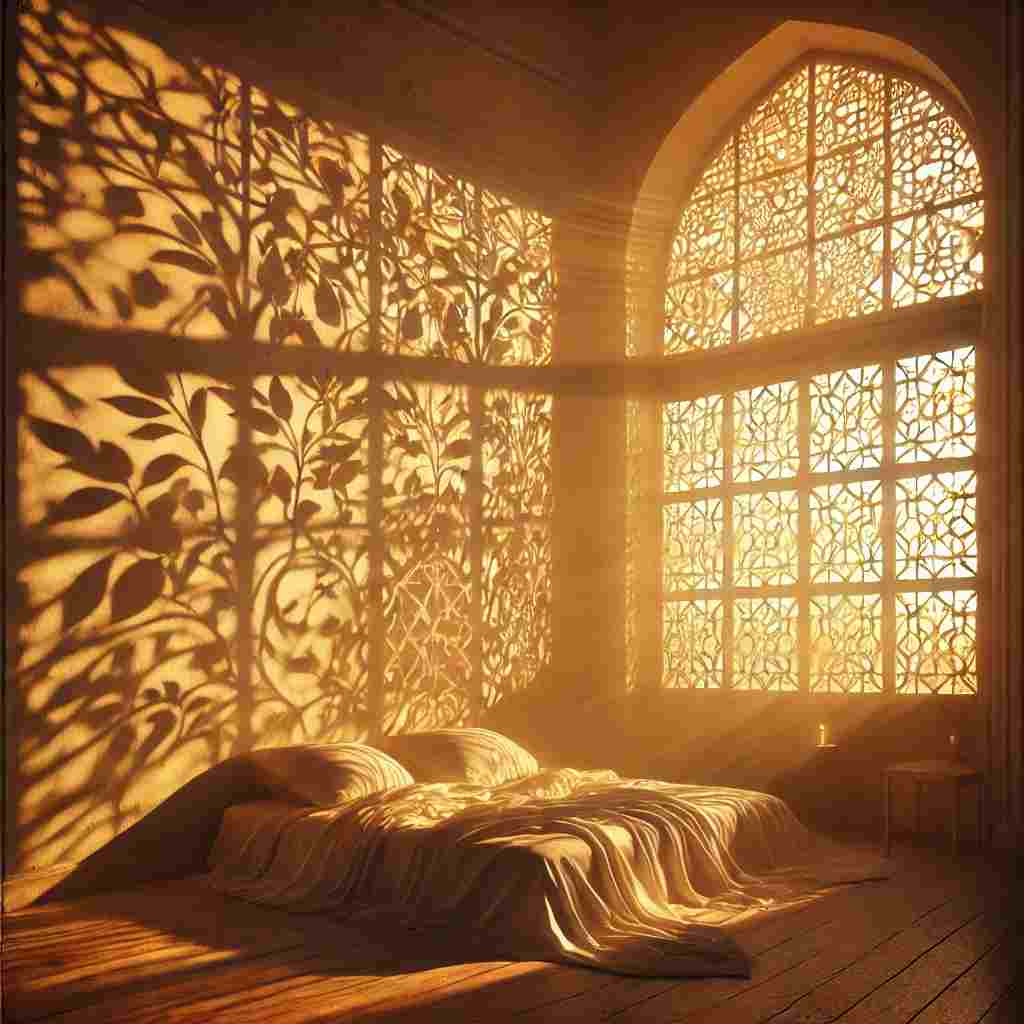

As on my bed at dawn I mused and prayed,

I saw my lattice prankt upon the wall,

The flaunting leaves and flitting birds withal—

A sunny phantom interlaced with shade;

"Thanks be to Heaven," in happy mood I said,

"What sweeter aid my matins could befall

Than this fair glory from the east hath made?

What holy sleights hath God, the Lord of all,

To bid us feel and see! We are not free

To say we see not, for the glory comes

Nightly and daily, like the flowing sea;

His lustre pierces through the midnight glooms,

And at prime hours, behold! he follows me

With golden shadows to my secret rooms."

Charles Tennyson Turner's Sunrise

Charles Tennyson Turner’s Sunrise is a contemplative poem that captures a moment of spiritual and sensory reverie inspired by the first light of dawn. Turner's work often delves into scenes of natural beauty intertwined with reflections on divine presence, and in this sonnet, he uses the sunrise as a symbol of God’s omnipresence and the unceasing wonder of creation. Through careful attention to light, shadow, and imagery, Turner creates a poem that is as much an act of worship as it is an appreciation of natural beauty.

Introduction

The poem follows a traditional English sonnet form, with its rhyme scheme (ABBAABBA CDCDCD) adhering to the Petrarchan model in the octave, and adopting a variant rhyme in the sestet. This structure allows Turner to first present a scene of dawn seen from his bed, leading to a concluding reflection on the omnipresence of God in the everyday world. The language is devotional, and Turner's reverence is expressed through both the diction and the rhythm, which mimics a quiet, meditative tone.

Light, Shadow, and “Sunny Phantoms”

The poem opens with the speaker lying in bed at dawn, “mused and prayed,” setting a tone of quiet meditation. The early morning light creates a “lattice prankt upon the wall,” a delicate interplay of sunlight, leaves, and shadows that appears almost like a tapestry. Turner’s choice of the word “prankt” is noteworthy; it connotes a decorative, almost playful quality, suggesting that the morning light has adorned his walls with nature’s art. The “sunny phantom interlaced with shade” implies that this vision is both ethereal and transient, capturing the ephemeral beauty of dawn.

Turner’s observation of the morning scene as a “sunny phantom” suggests a ghostly, mystical quality to the light, as if it is both there and not there, a temporary vision that speaks to something greater than itself. This ghostly description suggests that light itself is an intimation of divine presence, a fleeting yet powerful reminder of God’s omnipresence.

Devotional Tone and Gratitude

The speaker’s response to this scene is one of thanksgiving—“Thanks be to Heaven”—where his “happy mood” aligns with a spiritual gratitude. This gratitude is not only for the beauty of the dawn but for its function as an aid to his “matins,” or morning prayers. By framing this scene as an aid to his devotions, Turner implies that nature itself can be a form of prayer or communion with God. His “matins” are elevated by this vision of morning glory, a reflection of how the divine pervades even the simplest, most domestic settings.

Turner’s diction, particularly in words like “Heaven,” “glory,” and “holy sleights,” reinforces the religious significance of this moment. “Holy sleights” is a fascinating phrase, suggesting that God employs subtle tricks or illusions to reveal Himself. Rather than grand displays, it is these quiet, almost magical transformations of light and shadow that evoke in the speaker a sense of awe. The subtlety of this phrase conveys the mystery of divine manifestations in the natural world.

Divine Omnipresence and Humanity’s Receptivity

In the concluding sestet, Turner shifts his reflection to the idea that humanity is never free from God’s presence: “We are not free / To say we see not, for the glory comes / Nightly and daily.” This statement suggests a kind of spiritual obligation to acknowledge God’s beauty, which manifests continuously, like the “flowing sea.” Here, the reference to the sea’s ebb and flow becomes a powerful metaphor for the constancy and inevitability of divine presence. Just as the tides follow their ceaseless rhythm, God’s “glory” appears regularly in the cycles of nature, impressing itself upon the human soul.

This concept of unavoidable divine presence is enhanced by Turner’s assertion that God’s “lustre pierces through the midnight glooms.” By using “midnight glooms,” Turner implies that even in darkness or despair, God’s light finds a way to reach the individual, casting shadows that act as symbols of a higher order and purpose. The “golden shadows” that follow the speaker into his “secret rooms” evoke an image of God’s grace as both universal and intimate, extending from the vastness of the dawn to the private, inner spaces of the self.

The Paradox of Light and Shadow

Throughout the poem, Turner juxtaposes light and shadow, creating a paradox where light manifests itself through shade and shadow. This dynamic reflects the mystery of the divine: God’s presence is visible and yet veiled, revealed in fleeting visions that hint at an infinite reality beyond. The phrase “golden shadows” encapsulates this paradox perfectly—God’s light creates shadows, a reminder of how the divine can be both hidden and revealed in ordinary spaces. Turner’s expression of this paradox reinforces the idea that faith and perception are intricately bound together, where seeing the divine requires a kind of receptive, contemplative vision.

Conclusion

Charles Tennyson Turner’s Sunrise is a richly symbolic meditation on the interplay between light, nature, and divine presence. Through careful attention to light and shadow, Turner reveals how moments of natural beauty serve as reminders of a constant divine presence that pervades even the quietest moments. The poem suggests that nature, with its rhythms and fleeting beauties, is a medium through which the divine communicates with humanity. In viewing the sunrise, Turner not only finds beauty but also a spiritual message that resonates deeply within him, leaving readers with the impression that to truly see the world is to glimpse traces of the divine. The poem becomes a quiet, reverent celebration of a world where light and shadow work together to reveal the presence of God.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!