There Is No God

Arthur Hugh Clough

1819 to 1861

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

"There is no God," the wicked saith,

"And truly it's a blessing,

For what He might have done with us

It's better only guessing."

"There is no God," a youngster thinks,

"or really, if there may be,

He surely did not mean a man

Always to be a baby."

"There is no God, or if there is,"

The tradesman thinks, "'twere funny

If He should take it ill in me

To make a little money."

"Whether there be," the rich man says,

"It matters very little,

For I and mine, thank somebody,

Are not in want of victual."

Some others, also, to themselves,

Who scarce so much as doubt it,

Think there is none, when they are well,

And do not think about it.

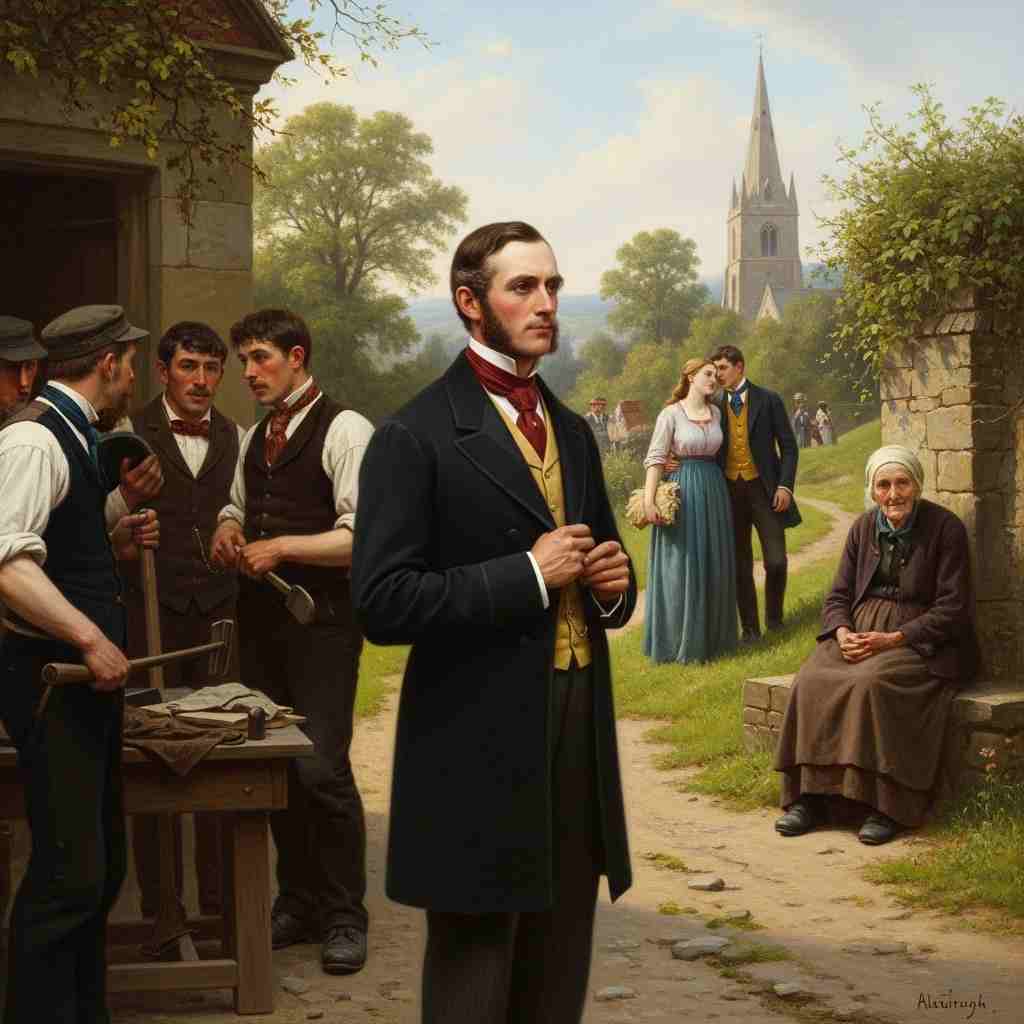

But country folks who live beneath

The shadow of the steeple;

The parson and the parson's wife,

And mostly married people;

Youths green and happy in first love,

So thankful for illusion;

And men caught out in what the world

Calls guilt, in first confusion;

And almost everyone when age,

Disease, or sorrows strike him,

Inclines to think there is a God,

Or something very like Him.

Arthur Hugh Clough's There Is No God

Arthur Hugh Clough’s "There Is No God" is a deceptively simple yet deeply provocative poem that interrogates the nature of belief, skepticism, and human self-interest. Written in the mid-19th century, a period marked by religious doubt, scientific advancement, and social upheaval, the poem captures the existential anxieties of its time while remaining strikingly relevant to modern readers. Through a series of vignettes, Clough presents a spectrum of disbelief, illustrating how different individuals rationalize their skepticism—or their latent faith—based on personal circumstance rather than philosophical rigor. This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its use of irony and structure, its central themes of doubt and self-deception, and its emotional resonance as a meditation on human vulnerability.

Historical and Cultural Context: Victorian Crisis of Faith

To fully appreciate Clough’s poem, one must situate it within the broader Victorian crisis of faith. The 19th century was an era of profound intellectual and spiritual turmoil, as scientific discoveries (particularly Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, published in 1859) and higher biblical criticism (such as Strauss’s The Life of Jesus) challenged traditional Christian dogma. Many Victorian intellectuals, including Clough’s close friend Matthew Arnold, grappled with the erosion of religious certainty. Clough himself was deeply influenced by these debates; his poetry often reflects a tension between skepticism and a longing for transcendent meaning.

"There Is No God" was written in 1849, a time when Clough was wrestling with his own faith. Having been raised in an evangelical household and educated at Oxford during the Tractarian movement, he was intimately familiar with religious fervor—and disillusionment. The poem’s sardonic tone suggests a weariness with both blind piety and shallow atheism, positioning it as a critique of facile belief systems, whether orthodox or secular.

Structure and Literary Devices: Irony and the Unreliable Speaker

The poem’s structure is a masterclass in irony. Each stanza presents a different speaker declaring, in some form, "There is no God," but their reasons for disbelief are invariably self-serving or circumstantial rather than philosophical. The wicked man dismisses God as a "blessing" because divine justice would be inconvenient; the youngster rejects faith because he resents moral constraints; the tradesman justifies greed; the rich man feels no need for God because he lacks nothing. These voices are not earnest truth-seekers but individuals constructing post-hoc rationalizations for their desires.

Clough’s use of free indirect discourse—a technique where the narrator adopts the voice of the characters—allows the poem to inhabit each speaker’s perspective without explicit judgment. Yet the cumulative effect is damning: the poem exposes how disbelief often stems from convenience rather than conviction. The final stanza, however, introduces a shift. Those who suffer—through age, disease, or sorrow—"Incline to think there is a God, / Or something very like Him." Here, Clough suggests that hardship, rather than comfort, prompts genuine existential questioning. The poem’s structure thus moves from glib dismissals to a more ambiguous, emotionally fraught conclusion.

Themes: Self-Interest, Suffering, and the Search for Meaning

At its core, "There Is No God" is a study in human self-deception. The early stanzas reveal how disbelief can be a form of moral evasion. The wicked man does not deny God on intellectual grounds but because acknowledging divine justice would unsettle his lifestyle. Similarly, the tradesman’s skepticism is a license for unethical behavior. Clough’s insight here is psychological as much as theological: people often shape their beliefs (or lack thereof) around their desires.

Yet the poem also explores how suffering disrupts complacency. The final lines suggest that those who experience pain—whether through guilt, illness, or loss—are more likely to confront existential questions. This aligns with a broader Victorian literary preoccupation with suffering as a catalyst for spiritual awakening (seen in works like Tennyson’s In Memoriam). Clough does not endorse a simplistic "God of the gaps" theology, where belief emerges only in desperation, but he does imply that hardship strips away the illusions that shield people from deeper reflection.

Comparative Analysis: Clough and His Contemporaries

Clough’s poem resonates with the works of other Victorian doubters, particularly Matthew Arnold and Thomas Hardy. Arnold’s "Dover Beach" similarly laments the "melancholy, long, withdrawing roar" of faith, though Arnold’s tone is more elegiac, whereas Clough’s is wry and satirical. Hardy’s "God’s Funeral" presents a more nihilistic vision, depicting belief as an obsolete relic. Clough, by contrast, does not fully dismiss the possibility of God; instead, he critiques the flimsiness of both belief and disbelief when they serve as mere coping mechanisms.

A more philosophical comparison can be drawn with Søren Kierkegaard, who argued that true faith requires a "leap" beyond rationality. Clough’s poem, in its own way, suggests that neither smug atheism nor unexamined theism constitutes an authentic engagement with the divine. Only in moments of crisis do people approach something like Kierkegaardian existential faith—or its shadow.

Biographical Insights: Clough’s Personal Struggles

Clough’s own life informs the poem’s ambivalence. After leaving Oxford due to religious doubts, he vacillated between skepticism and a residual hunger for spiritual meaning. His letters reveal a man torn between intellectual honesty and emotional yearning—a tension palpable in "There Is No God." The poem’s closing lines, with their tentative openness to the divine ("Or something very like Him"), reflect Clough’s refusal to settle into dogmatic atheism or orthodoxy. This ambivalence makes the poem more than a satire; it is also a confession of unresolved longing.

Emotional Impact: The Lingering Question

What gives "There Is No God" its enduring power is its refusal to provide easy answers. The poem does not champion atheism or faith but instead exposes the human tendency to adopt beliefs—or reject them—for selfish reasons. The final stanza’s quiet shift in tone, from irony to something more vulnerable, invites readers to consider their own moments of doubt and yearning. The emotional weight lies in the suggestion that only suffering strips away our pretenses, forcing us to confront life’s biggest questions without the armor of certainty.

Conclusion: A Poem for Then and Now

Clough’s "There Is No God" remains strikingly relevant in an age where belief and disbelief are often performative, shaped by identity politics or personal convenience rather than deep inquiry. The poem’s brilliance lies in its psychological acuity, its ironic detachment, and its ultimate refusal to let anyone—believer or skeptic—off the hook. By framing disbelief as a series of rationalizations, Clough challenges readers to examine their own convictions. And in its closing lines, the poem hints at something more profound: that the search for meaning is not a matter of intellectual debate but of lived experience, often emerging most urgently in our moments of greatest vulnerability.

In this way, "There Is No God" transcends its Victorian context, speaking to anyone who has ever questioned, doubted, or hoped in the face of life’s uncertainties. It is not a poem of answers, but of uncomfortable, necessary questions—and in that, it achieves a rare and lasting resonance.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more