Morning at the Window

T. S. Eliot

1888 to 1965

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

They are rattling breakfast plates in basement kitchens,

And along the trampled edges of the street

I am aware of the damp souls of housemaids

Sprouting despondently at area gates.

The brown waves of fog toss up to me

Twisted faces from the bottom of the street,

And tear from a passer-by with muddy skirts

An aimless smile that hovers in the air

And vanishes along the level of the roofs.

T. S. Eliot's Morning at the Window

T.S. Eliot’s poem Morning at the Window is an evocative urban vignette that captures the alienation and bleakness of modern city life. Written in free verse, the poem uses fragmented imagery, personification, and subtle shifts in tone to convey a sense of disconnection and despair. It aligns with Eliot’s early style, often associated with his exploration of urban modernity and the emotional desolation it imposes on individuals.

Setting and Context

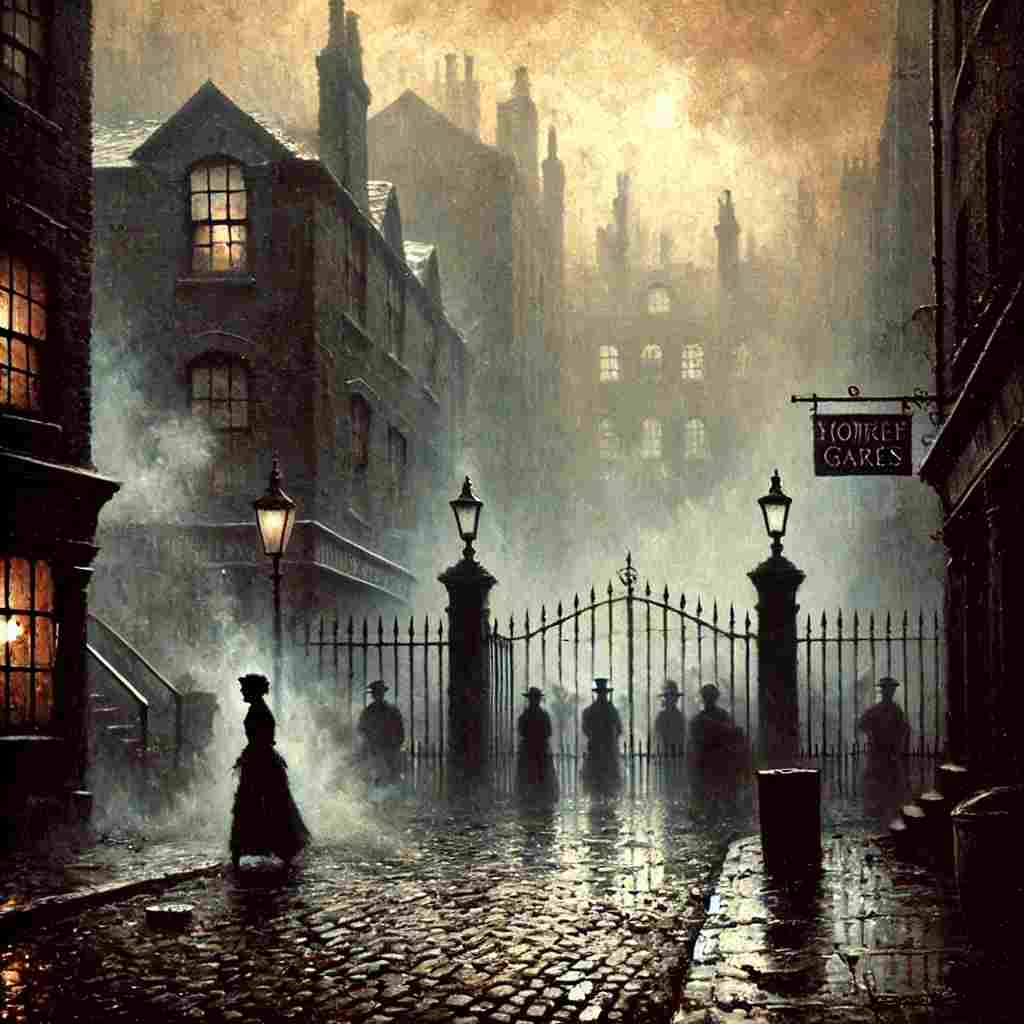

The poem is set in a cityscape, likely London, where Eliot lived and which frequently serves as a backdrop for his early work. The title, Morning at the Window, suggests a detached observational perspective, with the speaker positioned as an onlooker, separated from the activities of those below.

The "window" symbolizes a barrier between the speaker and the external world, underscoring themes of isolation. This separation not only highlights the speaker’s physical distance but also conveys an emotional and existential alienation—a hallmark of modernist literature.

Imagery and Symbolism

The opening lines introduce the clatter of “breakfast plates in basement kitchens,” grounding the poem in a quotidian urban scene. The “basement kitchens” evoke a sense of hidden, lower-class labor, emphasizing the stratification of society. The sound of rattling plates is discordant, contributing to the atmosphere of unease.

The metaphor of “the damp souls of housemaids” adds an almost ghostly quality to these workers. Describing them as “sprouting despondently at area gates” likens them to neglected plants, suggesting stagnation and despair. This organic imagery conveys both the dehumanization and the monotony of their lives.

The phrase “brown waves of fog” further reinforces the oppressive mood, with the fog acting as a symbol of urban pollution and moral obscurity. It embodies the physical and emotional murkiness of the environment.

Fragmented Human Presence

Eliot’s urban landscape is populated by disembodied or partial presences. The “twisted faces from the bottom of the street” evoke a distorted humanity, reflecting not only the literal obscuring of faces by fog but also the alienating effects of modernity. These “twisted faces” seem to reach toward the speaker, yet they remain inaccessible, deepening the poem’s theme of separation.

The passer-by with “muddy skirts” is similarly fragmented, defined only by a fleeting “aimless smile.” This smile, described as “hovering in the air / And vanish[ing] along the level of the roofs,” is a poignant symbol of fleeting connection, impermanent and inconsequential in the vast, impersonal cityscape. Eliot’s language suggests that even human gestures—smiles—are stripped of meaning and permanence.

Tone and Mood

The poem’s tone is one of melancholy detachment. The speaker observes the scene without participating, emphasizing their emotional distance from the world below. This detachment mirrors the modernist preoccupation with the alienation of the individual in a fragmented, mechanized society.

Eliot’s free verse structure complements the poem’s mood, rejecting traditional rhythmic regularity and formal rhyme schemes to create a fluid, observational quality. The lack of a clear resolution or narrative reinforces the theme of existential uncertainty.

Conclusion

Morning at the Window encapsulates the dissonance and despair of urban life in the modernist era. Through vivid imagery, fragmented human interactions, and a pervasive atmosphere of alienation, Eliot offers a profound meditation on the emotional toll of modern existence. The poem’s focus on fleeting impressions and impermanence aligns with his broader concerns in Prufrock and Other Observations (1917), presenting a world where connection and meaning remain elusive.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!