Gunga Din

Rudyard Kipling

1865 to 1936

You may talk o’ gin and beer

When you’re quartered safe out ’ere,

An’ you’re sent to penny-fights an’ Aldershot it;

But when it comes to slaughter

You will do your work on water,

An’ you’ll lick the bloomin’ boots of ’im that’s got it.

Now in Injia’s sunny clime,

Where I used to spend my time

A-servin’ of ’Er Majesty the Queen,

Of all them blackfaced crew

The finest man I knew

Was our regimental bhisti, Gunga Din,

He was ‘Din! Din! Din!

‘You limpin’ lump o’ brick-dust, Gunga Din!

‘Hi! Slippy hitherao

‘Water, get it! Panee lao,

‘You squidgy-nosed old idol, Gunga Din.’

The uniform ’e wore

Was nothin’ much before,

An’ rather less than ’arf o’ that be’ind,

For a piece o’ twisty rag

An’ a goatskin water-bag

Was all the field-equipment ’e could find.

When the sweatin’ troop-train lay

In a sidin’ through the day,

Where the ’eat would make your bloomin’ eyebrows crawl,

We shouted ‘Harry By!’

Till our throats were bricky-dry,

Then we wopped ’im ’cause ’e couldn’t serve us all.

It was ‘Din! Din! Din!

‘You ’eathen, where the mischief ’ave you been?

‘You put some juldee in it

‘Or I’ll marrow you this minute

‘If you don’t fill up my helmet, Gunga Din!’

’E would dot an’ carry one

Till the longest day was done;

An’ ’e didn’t seem to know the use o’ fear.

If we charged or broke or cut,

You could bet your bloomin’ nut,

’E’d be waitin’ fifty paces right flank rear.

With ’is mussick on ’is back,

’E would skip with our attack,

An’ watch us till the bugles made 'Retire,’

An’ for all ’is dirty ’ide

’E was white, clear white, inside

When ’e went to tend the wounded under fire!

It was ‘Din! Din! Din!’

With the bullets kickin’ dust-spots on the green.

When the cartridges ran out,

You could hear the front-ranks shout,

‘Hi! ammunition-mules an' Gunga Din!’

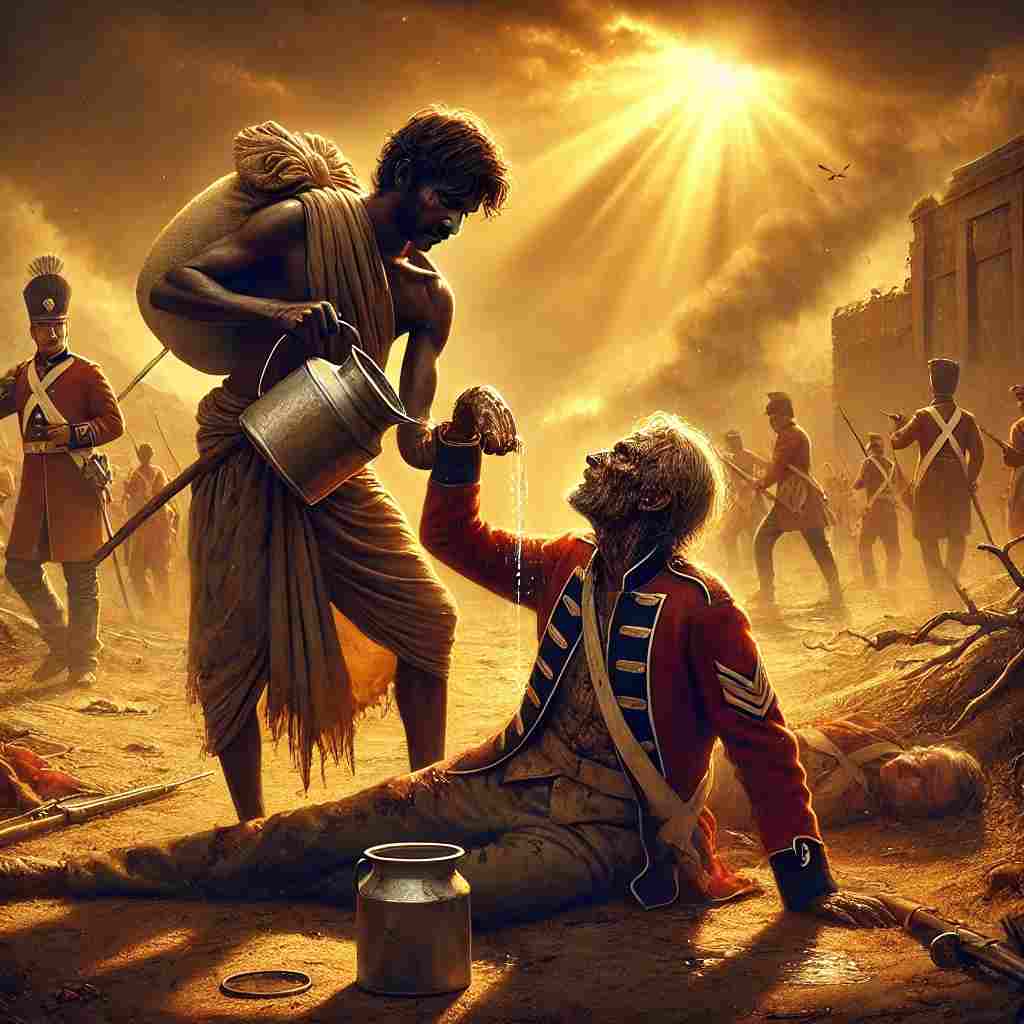

I shan’t forgit the night

When I dropped be’ind the fight

With a bullet where my belt-plate should ’a’ been.

I was chokin’ mad with thirst,

An’ the man that spied me first

Was our good old grinnin’, gruntin’ Gunga Din.

’E lifted up my ’ead,

An’ he plugged me where I bled,

An’ ’e guv me ’arf-a-pint o’ water green.

It was crawlin’ and it stunk,

But of all the drinks I’ve drunk,

I’m gratefullest to one from Gunga Din.

It was 'Din! Din! Din!

‘’Ere’s a beggar with a bullet through ’is spleen;

‘’E's chawin’ up the ground,

‘An’ ’e’s kickin’ all around:

‘For Gawd’s sake git the water, Gunga Din!’

’E carried me away

To where a dooli lay,

An’ a bullet come an’ drilled the beggar clean.

’E put me safe inside,

An’ just before ’e died,

'I ’ope you liked your drink,’ sez Gunga Din.

So I’ll meet ’im later on

At the place where ’e is gone—

Where it’s always double drill and no canteen.

’E’ll be squattin’ on the coals

Givin’ drink to poor damned souls,

An’ I’ll get a swig in hell from Gunga Din!

Yes, Din! Din! Din!

You Lazarushian-leather Gunga Din!

Though I’ve belted you and flayed you,

By the livin’ Gawd that made you,

You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!

Rudyard Kipling's Gunga Din

Rudyard Kipling’s Gunga Din (1890) is a celebrated narrative poem that blends the vernacular of British soldiers in colonial India with a poignant tale of sacrifice and moral reckoning. Through the figure of Gunga Din, an Indian water-bearer serving British troops, Kipling examines themes of colonialism, racial prejudice, and human dignity. The poem’s rhythmic ballad form, evocative imagery, and stark contrast between its narrator’s crudeness and Gunga Din’s heroism reveal the complex dynamics of imperialism and personal valor.

Form and Structure

The poem is written in rhymed quatrains with an ABAB rhyme scheme, reflecting the sing-song cadence of a soldiers’ chant or march. The rhythm, predominantly anapestic, evokes the brisk energy of military life and underscores the tension and action within the narrative. This metrical regularity is disrupted at points of emotional or dramatic intensity, emphasizing key moments such as Gunga Din’s death and the narrator’s final revelation.

Narrative Voice and Language

Kipling employs the voice of a rough, colloquial British soldier, whose dialect—filled with contractions (“’ere,” “’arf,” “bloomin’”) and slang—captures the everyday speech of the rank-and-file troops. The narrator’s casual racism and dismissive attitude toward Gunga Din as a "’eathen" reflect the prevalent prejudices of the time. Yet, his grudging admiration grows throughout the poem, culminating in the ultimate admission: “You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!”

This evolving perspective mirrors a moral journey. The narrator begins with contempt but is forced to confront the disparity between Gunga Din’s selflessness and his own moral shortcomings. The use of vernacular language humanizes the narrator, making his final acknowledgment of Gunga Din’s superiority emotionally impactful.

Themes

Colonialism and Racial Prejudice

The relationship between the British soldiers and Gunga Din is emblematic of colonial hierarchies. Gunga Din is demeaned as a "blackfaced crew" and a "squidgy-nosed old idol," reflecting the racialized power dynamics of British imperialism. However, Kipling critiques these attitudes by depicting Gunga Din’s inherent nobility and bravery in stark contrast to the cruelty and ingratitude of his colonial masters. The poem thus exposes the moral bankruptcy of imperialist ideologies while also portraying the essential humanity of the colonized subject.

Heroism and Sacrifice

Gunga Din’s heroism lies in his unwavering commitment to serving others, even under dire circumstances. Despite being mistreated, he repeatedly risks his life to provide water and aid to the soldiers, embodying the virtues of courage, duty, and compassion. His death while saving the narrator epitomizes ultimate self-sacrifice. The line “’E was white, clear white, inside” inverts the racist assumptions of the era, suggesting that true virtue transcends race.

Moral Reckoning

The narrator’s transformation from a mocking, abusive figure to one who reveres Gunga Din serves as a moral arc. His closing admission—“You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!”—represents a moment of humility and a critique of his own complicity in the colonial system’s dehumanization. This acknowledgment lends the poem a redemptive quality, highlighting the possibility of recognizing shared humanity across cultural divides.

Imagery and Symbolism

- Water as a Symbol: Water is central to Gunga Din’s role and symbolic of life and salvation. His unrelenting effort to supply water, even at the cost of his own life, frames him as a Christ-like figure, offering redemption and sustenance to those who demean him.

- Fire and Hell: The poem’s imagery of “squattin’ on the coals” and giving “drink to poor damned souls” situates Gunga Din in a paradoxical role as a savior in the afterlife, continuing to serve others even in hell. This reinforces his spiritual superiority over his tormentors.

- Uniform and Equipment: The contrast between the British soldiers’ military gear and Gunga Din’s meager attire (a "twisty rag" and "goatskin water-bag") underscores the inequities of colonial service while highlighting Gunga Din’s resilience.

Conclusion

Gunga Din is both a tribute to individual courage and a subtle critique of imperialism. While Kipling’s own views on empire were often complex and contradictory, this poem transcends its colonial context to deliver a universal message about the dignity of selfless service and the possibility of moral redemption. By contrasting the rough soldier’s perspective with Gunga Din’s quiet heroism, Kipling invites readers to question the racial and social hierarchies that devalue human life. The poem’s enduring power lies in its ability to evoke both admiration for its titular character and discomfort with the systemic injustices he endured.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!