Come Away, Death

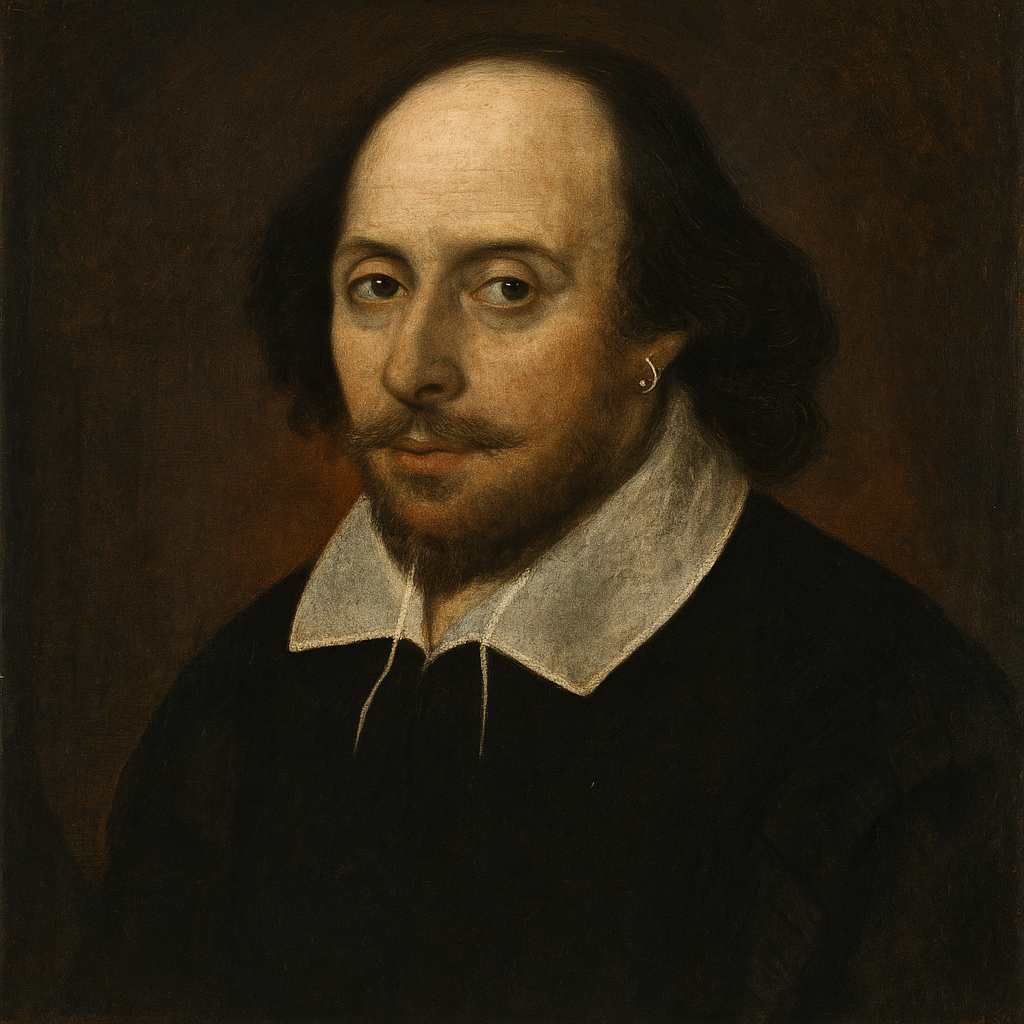

William Shakespeare

1564 to 1616

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

Come away, come away, death,

And in sad cypress let me be laid.

Fly away, fly away, breath;

I am slain by a fair cruel maid.

My shroud of white, stuck all with yew,

O, prepare it!

My part of death, no one so true

Did share it.

Not a flower, not a flower sweet,

On my black coffin let there be strown.

Not a friend, not a friend greet

My poor corpse, where my bones shall be thrown.

A thousand thousand sighs to save,

Lay me, O, where

Sad true lover never find my grave,

To weep there!

William Shakespeare's Come Away, Death

William Shakespeare’s Come Away, Death is a haunting lament that explores themes of love, death, and despair with striking emotional intensity. Though brief, the poem is rich in imagery, cultural allusions, and psychological depth, offering a window into Renaissance attitudes toward mortality and unrequited love. This essay will examine the poem’s historical and cultural context, its literary devices, central themes, and emotional resonance, while also considering its place within Shakespeare’s broader body of work.

Historical and Cultural Context

Come Away, Death appears in Twelfth Night (Act II, Scene IV), where it is sung by Feste, the fool, at the request of Duke Orsino. The song’s melancholic tone contrasts sharply with the play’s comedic elements, underscoring the Duke’s self-indulgent sorrow over his unrequited love for Olivia. The poem’s themes of death and despair reflect the Renaissance fascination with the interplay between love and mortality, a recurring motif in Shakespeare’s sonnets and tragedies.

During the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, death was an ever-present reality due to plague, war, and high mortality rates. The memento mori tradition—artistic and literary reminders of death’s inevitability—permeated the culture. Shakespeare’s poem engages with this tradition, presenting death not as a distant abstraction but as an immediate, almost seductive force. The speaker’s plea to be buried without flowers or mourners suggests a rejection of conventional funeral rites, emphasizing the isolating nature of grief.

Additionally, the poem’s depiction of love as a fatal wound aligns with the Petrarchan tradition, in which the beloved is often portrayed as a cruel, unattainable figure who inflicts emotional torment. The speaker’s claim to be "slain by a fair cruel maid" echoes the hyperbolic language of courtly love poetry, where love is both ecstasy and agony.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Shakespeare employs a range of literary devices to heighten the poem’s emotional impact. The most striking is its funereal imagery, which constructs a vivid picture of death and burial:

-

"Sad cypress" (l. 2): Cypress wood was traditionally used for coffins, symbolizing mourning.

-

"Shroud of white, stuck all with yew" (l. 5): The yew tree, often found in graveyards, was associated with death and immortality.

-

"Black coffin" (l. 9): The absence of flowers underscores the speaker’s desire for a bleak, solitary burial.

The poem’s repetition ("Come away, come away, death"; "Fly away, fly away, breath") creates a hypnotic, incantatory rhythm, as if the speaker is summoning death itself. The imperative tone suggests both resignation and agency—the speaker does not merely await death but actively calls for it.

Personification is another key device. Death is not an abstract concept but an entity that can be summoned ("Come away, death"), while breath is something that can "fly away." This anthropomorphism intensifies the poem’s emotional urgency, blurring the line between life and death.

The contrast between love and death is central to the poem’s meaning. The speaker describes himself as "slain by a fair cruel maid," framing love as a fatal wound. This paradoxical fusion of eros (love) and thanatos (death) was a common motif in Renaissance literature, seen in works like John Donne’s The Canonization and Shakespeare’s own Romeo and Juliet.

Themes: Love, Death, and Isolation

1. Love as a Mortal Wound

The poem’s most explicit theme is the lethal power of unrequited love. The speaker does not merely suffer from heartbreak—he is slain by it. This hyperbolic language aligns with the Petrarchan tradition, where love is both ecstatic and destructive. The beloved’s cruelty ("a fair cruel maid") transforms love from a life-affirming force into a death sentence.

2. The Desire for Oblivion

Unlike conventional elegies that seek remembrance, the speaker rejects mourning rituals:

"Not a flower, not a flower sweet, / On my black coffin let there be strown. / Not a friend, not a friend greet / My poor corpse, where my bones shall be thrown."

This rejection of flowers and mourners suggests a desire for complete erasure, as if the speaker’s suffering is too profound for conventional expressions of grief. The final lines—"Sad true lover never find my grave, / To weep there!"—reinforce this, implying that even the sympathy of fellow sufferers would be unbearable.

3. The Intersection of Eros and Thanatos

Freud’s concept of the death drive (Thanatos)—the unconscious impulse toward self-destruction—resonates with the poem’s tone. The speaker does not resist death but embraces it, framing it as a release from the torment of love. This intertwining of love and death is a recurring motif in Shakespeare’s works, from Romeo and Juliet ("Thus with a kiss I die") to the sonnets ("Love is not love / Which alters when it alteration finds").

Comparative Analysis

Come Away, Death shares thematic and stylistic similarities with other Renaissance poems:

-

John Donne’s The Apparition: Both poems depict love as fatal, though Donne’s speaker is vengeful rather than resigned.

-

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 71 ("No longer mourn for me when I am dead"): Like Come Away, Death, this sonnet rejects posthumous mourning.

-

Thomas Nashe’s In Time of Pestilence: Both works reflect the Renaissance preoccupation with death, though Nashe’s tone is more nihilistic.

Within Twelfth Night itself, the song contrasts with Feste’s other lighthearted tunes, highlighting the play’s underlying melancholy. While Twelfth Night is a comedy, it contains moments of profound sorrow—reminding audiences that even in laughter, grief lingers.

Emotional Impact and Philosophical Undercurrents

The poem’s emotional power lies in its stark simplicity. Unlike Shakespeare’s more elaborate soliloquies, Come Away, Death is concise, almost austere, amplifying its despair. The speaker’s plea for an unmourned burial evokes existential loneliness—a rejection of the communal rituals that typically provide solace in death.

Philosophically, the poem raises questions about the nature of grief and the futility of love. Is the speaker’s despair self-indulgent (as Orsino’s is in Twelfth Night), or does it express a universal truth about the agony of unrequited love? The lack of resolution—no redemption, no catharsis—makes the poem all the more haunting.

Conclusion

Come Away, Death is a masterful exploration of love’s destructive potential and the longing for oblivion. Through its vivid imagery, incantatory rhythm, and stark emotional honesty, the poem transcends its theatrical context, speaking to timeless human experiences of grief and despair. While it may be a brief interlude in Twelfth Night, its resonance is profound, reminding us of Shakespeare’s unparalleled ability to distill complex emotions into a few, devastating lines.

In the broader scope of Renaissance literature, the poem exemplifies the era’s preoccupation with the interplay of love and death, while its rejection of conventional mourning rituals anticipates modern existentialist themes. Ultimately, Come Away, Death is not just a song of sorrow—it is a meditation on the unbearable weight of love, the seduction of nothingness, and the silence that follows the last sigh.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!