A Light in the Moon

Gertrude Stein

1874 to 1946

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

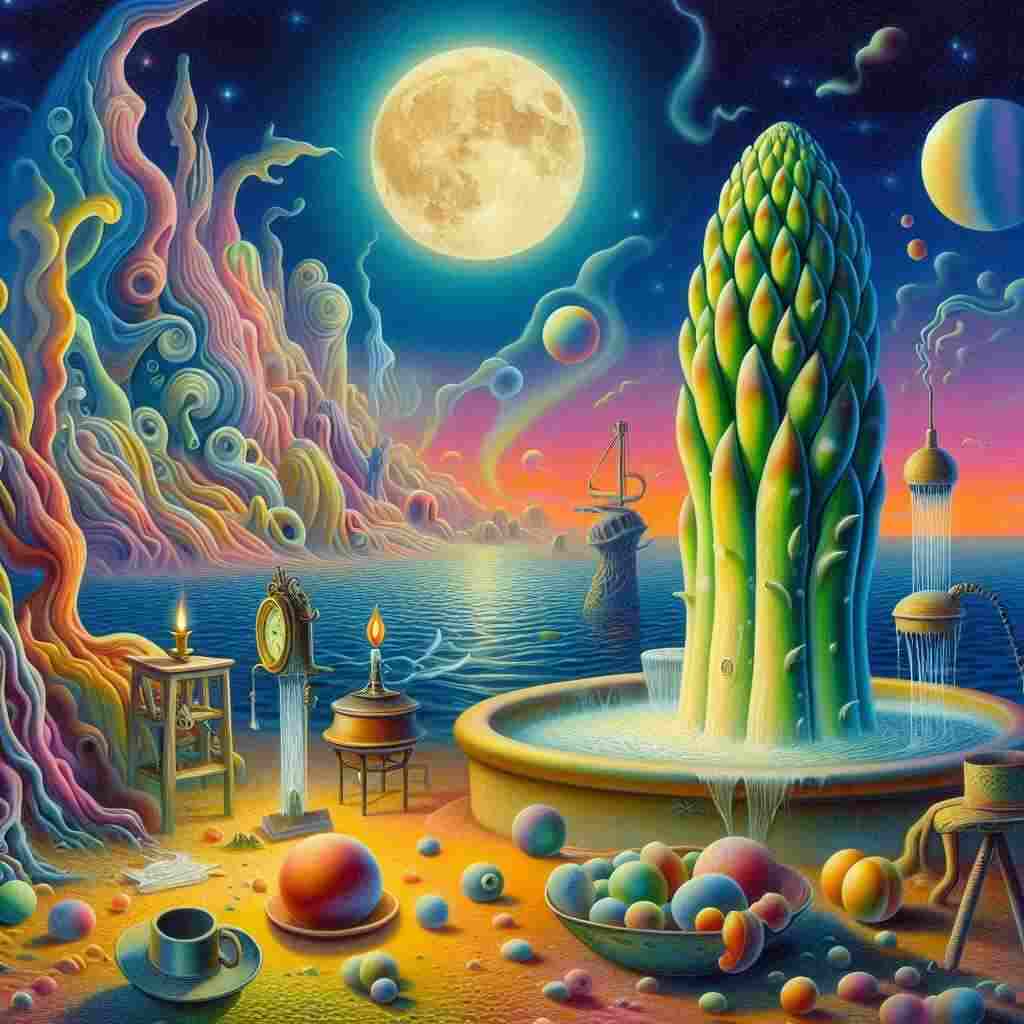

A light in the moon the only light is on Sunday. What was the sensible decision. The sensible decision was that notwithstanding many declarations and more music, not even withstanding the choice and a torch and a collection, notwithstanding the celebrating hat and a vacation and even more noise than cutting, notwithstanding Europe and Asia and being overbearing, not even notwithstanding an elephant and a strict occasion, not even withstanding more cultivation and some seasoning, not even with drowning and with the ocean being encircling, not even with more likeness and any cloud, not even with terrific sacrifice of pedestrianism and a special resolution, not even more likely to be pleasing. The care with which the rain is wrong and the green is wrong and the white is wrong, the care with which there is a chair and plenty of breathing. The care with which there is incredible justice and likeness, all this makes a magnificent asparagus, and also a fountain.

Gertrude Stein's A Light in the Moon

Introduction

Gertrude Stein's poem "A Light in the Moon" presents a formidable challenge to conventional literary analysis, embodying the avant-garde spirit of modernism in its seemingly impenetrable prose. This essay aims to unravel the complex tapestry of Stein's work, examining its linguistic innovations, thematic undercurrents, and cultural significance within the broader context of early 20th-century literature.

The Disruption of Linguistic Norms

Stein's poem immediately confronts the reader with its unconventional structure and syntax. The absence of traditional poetic devices such as meter, rhyme, or stanzaic organization signals a deliberate departure from established literary norms. This linguistic rebellion aligns with Stein's broader artistic project of destabilizing the relationship between signifier and signified, challenging readers to reconsider the very foundations of meaning-making in language.

The repetitive use of phrases like "notwithstanding" and "the care with which" creates a rhythmic pulse throughout the piece, evoking a sense of incantation or ritual. This repetition serves not only as a structural device but also as a means of emphasizing the poem's central preoccupations with decision-making, perception, and the nature of reality.

Temporal and Spatial Disorientation

The poem opens with a striking temporal marker: "A LIGHT in the moon the only light is on Sunday." This enigmatic statement immediately disorients the reader, conflating celestial illumination with a specific day of the week. The juxtaposition of cosmic and mundane elements sets the stage for the poem's exploration of the intersection between the ethereal and the quotidian.

Throughout the piece, Stein weaves together disparate geographical and cultural references, mentioning "Europe and Asia" alongside more abstract concepts like "justice" and "likeness." This global scope, combined with the poem's non-linear progression, creates a sense of spatial and temporal fluidity that mirrors the modernist preoccupation with the fragmentation of experience in an increasingly interconnected world.

The Paradox of Decision-Making

Central to the poem is the notion of "the sensible decision," a phrase that appears early and reverberates throughout the text. Stein's exploration of decision-making is characterized by contradiction and ambiguity. The repeated use of "notwithstanding" followed by a litany of potential influences on the decision process—ranging from "declarations and more music" to "terrific sacrifice of pedestrianism"—suggests the overwhelming complexity of choice in the modern world.

The poem's structure, with its long, winding sentences and accumulation of clauses, mimics the labyrinthine nature of decision-making itself. Stein's refusal to provide a clear resolution or outcome to this process reflects a modernist skepticism towards the possibility of rational, linear progress in human affairs.

The Subversion of Sensory Experience

Stein's poem is replete with sensory imagery, yet these images are often presented in ways that challenge conventional perception. The assertion that "the rain is wrong and the green is wrong and the white is wrong" disrupts our usual associations with these natural phenomena, forcing readers to question the reliability of their sensory experiences.

This subversion of sensory norms extends to the poem's surprising juxtapositions, such as the pairing of "a magnificent asparagus, and also a fountain" in the final line. By bringing together seemingly unrelated objects and concepts, Stein invites readers to forge new connections and ways of seeing the world around them.

The Role of Art and Creativity

Despite its apparent nonsensicality, "A Light in the Moon" can be read as a meditation on the creative process itself. The poem's emphasis on "care" and "incredible justice and likeness" suggests a concern with artistic precision and representation. However, these traditional artistic values are set against a backdrop of chaos and contradiction, reflecting the modernist struggle to find new modes of expression in a world that defies easy categorization.

The poem's final image of the asparagus and fountain could be interpreted as a metaphor for the artwork itself—an entity that grows organically (like the asparagus) yet is also shaped by human intervention and design (like the fountain). This dual nature of art as both natural and artificial, spontaneous and carefully crafted, encapsulates the modernist aesthetic that Stein helped to pioneer.

Cultural and Historical Context

To fully appreciate Stein's poem, it is crucial to consider its place within the broader cultural and historical context of the early 20th century. Written during a period of rapid technological advancement, social upheaval, and shifting global power dynamics, "A Light in the Moon" reflects the sense of disorientation and fragmentation that characterized the modernist worldview.

The poem's references to "Europe and Asia" and "the ocean being encircling" evoke the increasingly interconnected global landscape of Stein's time, while its emphasis on decision-making in the face of overwhelming stimuli speaks to the challenges of navigating an increasingly complex world.

Moreover, Stein's radical experimentation with language can be seen as a response to the inadequacy of traditional modes of expression in capturing the realities of modern life. By breaking down linguistic conventions, Stein seeks to create a new form of communication more suited to the fragmented, multifaceted nature of contemporary experience.

Feminist and Queer Readings

While not explicitly gendered, "A Light in the Moon" invites feminist and queer interpretations that consider Stein's position as a woman and a lesbian in the male-dominated literary world of her time. The poem's resistance to linear logic and its emphasis on circular, repetitive structures can be read as a challenge to patriarchal modes of thinking and writing.

Furthermore, the poem's celebration of the domestic sphere—evidenced by references to chairs, hats, and asparagus—alongside more traditionally "masculine" concerns like decision-making and justice, suggests a blurring of gender roles and a reclamation of the feminine as a site of artistic and philosophical inquiry.

Conclusion

Gertrude Stein's "A Light in the Moon" stands as a testament to the power of avant-garde literature to challenge our perceptions and expand the boundaries of linguistic expression. Through its radical deconstruction of syntactic norms, its exploration of the complexities of modern experience, and its playful approach to meaning-making, the poem continues to offer rich material for analysis and interpretation more than a century after its creation.

As we grapple with Stein's enigmatic text, we are reminded of the enduring relevance of modernist experimentation in our own era of information overload and shifting paradigms. "A Light in the Moon" invites us to embrace ambiguity, to find beauty in the absurd, and to continually question our assumptions about language, art, and the nature of reality itself.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more