An End

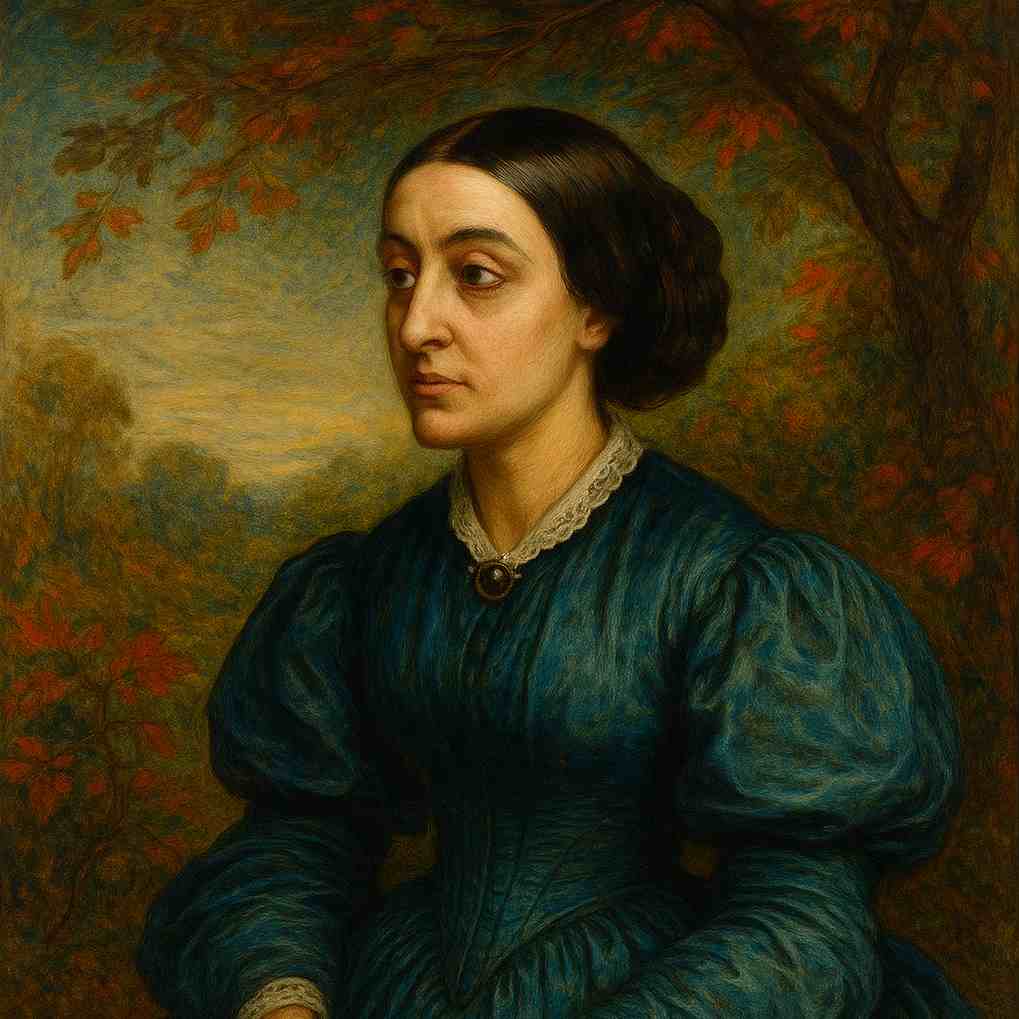

Christina Rossetti

1830 to 1894

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

Love, strong as Death, is dead.

Come, let us make his bed

Among the dying flowers:

A green turf at his head;

And a stone at his feet,

Whereon we may sit

In the quiet evening hours.

He was born in the Spring,

And died before the harvesting:

On the last warm summer day

He left us; he would not stay

For autumn twilight, cold and gray.

Sit we by his grave, and sing

He is gone away.

To few chords and sad and low

Sing we so:

Be our eyes fixed on the grass

Shadow-veiled as the years pass,

While we think of all that was

In the long ago.

Christina Rossetti's An End

Christina Rossetti’s An End is a poignant meditation on love, mortality, and the passage of time. Written with the economy and precision characteristic of her best work, the poem distills profound grief into a series of stark, evocative images. While its brevity might suggest simplicity, An End is a richly layered text that rewards close reading, offering insights into Rossetti’s preoccupations with loss, the natural world, and the transient nature of human affection. This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional resonance, while also considering its place within Rossetti’s broader oeuvre and the Victorian literary tradition.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate An End, one must situate it within the Victorian era’s complex attitudes toward death, mourning, and love. The 19th century was marked by an intense cultural fascination with mortality, evidenced by the popularity of elegiac poetry, the elaborate rituals of mourning (such as those following Prince Albert’s death), and the rise of spiritualism as a response to grief. Rossetti, whose life was shadowed by illness, loss, and unfulfilled romantic attachments, frequently explored these themes in her work.

Moreover, the Victorian period saw a tension between religious faith and growing scientific skepticism. Rossetti, a devout Anglican, often grappled with questions of divine love versus earthly impermanence. In An End, the death of love itself—rather than a person—becomes the subject of mourning, suggesting a metaphysical inquiry into whether human affection can ever be eternal. The poem’s setting, with its references to seasonal change and natural decay, also aligns with the Victorian interest in nature as both a symbol of cyclical renewal and a reminder of inevitable decline.

Literary Devices and Structure

Despite its brevity, An End employs a range of literary techniques that amplify its emotional weight.

1. Symbolism and Imagery

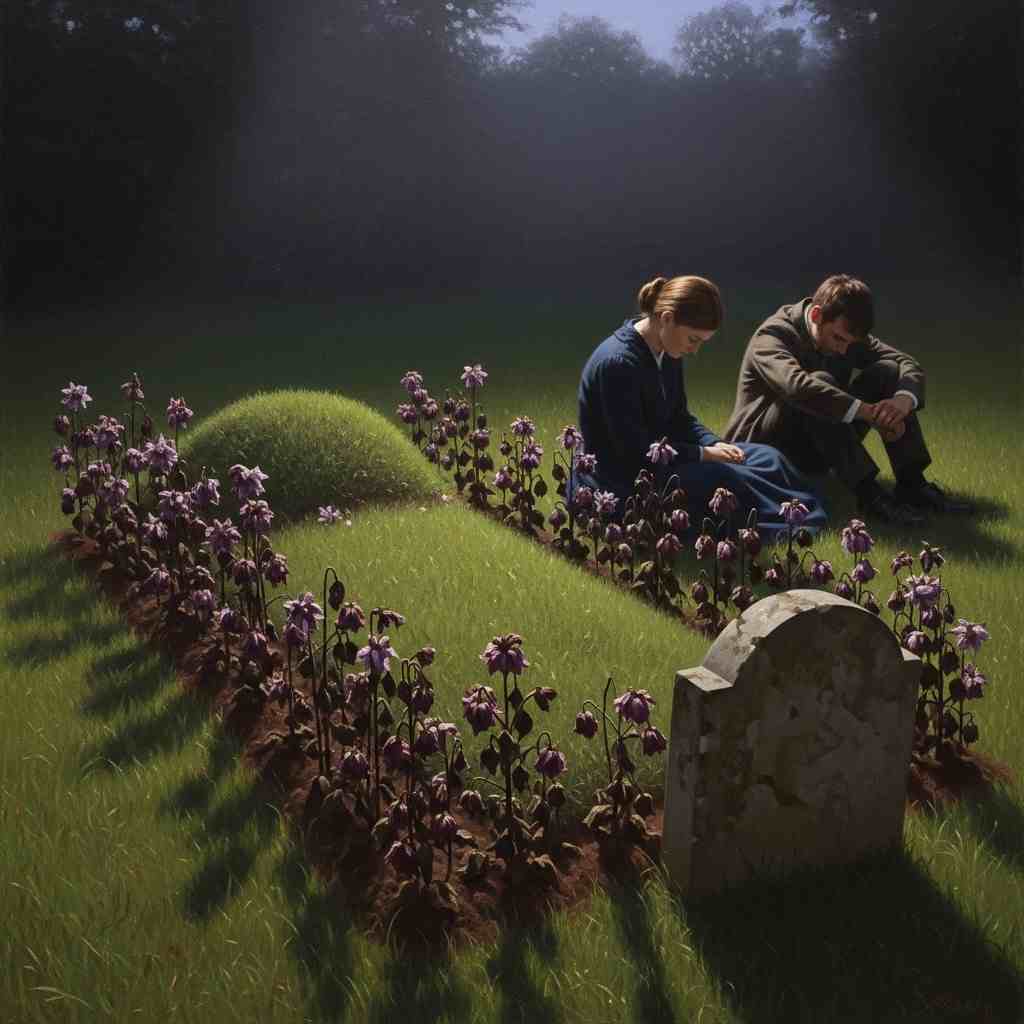

Rossetti’s use of natural imagery is particularly striking. The "dying flowers" and "green turf" evoke a gravesite, but they also serve as metaphors for love’s fleeting vitality. The contrast between the "last warm summer day" and the impending "autumn twilight, cold and gray" mirrors the transition from passion to desolation. The "stone at his feet" where the mourners sit suggests both a tombstone and a place of contemplation, reinforcing the poem’s meditation on permanence versus transience.

2. Personification

The poem hinges on the personification of love as a deceased being, "strong as Death, is dead." This paradoxical formulation—strength succumbing to mortality—echoes biblical language (Song of Solomon 8:6: "Love is strong as death") while subverting it. Rossetti suggests that even the most powerful human emotions are subject to decay, a theme that resonates with her other works, such as Remember and After Death.

3. Repetition and Refrain

The phrase "He is gone away" functions as a lament, its simplicity underscoring the finality of loss. The repetition of "sing we so" and the directive to "sit we by his grave" create a ritualistic quality, as if the poem itself is a funeral rite. This incantatory rhythm draws the reader into the collective act of mourning.

4. Temporal Contrasts

Rossetti juxtaposes different temporal states—birth ("He was born in the Spring"), death ("died before the harvesting"), and memory ("the long ago")—to emphasize love’s abrupt end. The harvesting metaphor is especially potent, implying that love was cut down before it could reach fruition, a theme that recurs in her poetry (e.g., Goblin Market’s exploration of unfulfilled desire).

Themes

1. The Transience of Love

The central theme of An End is the impermanence of love. Unlike the biblical assertion that love is as strong as death, Rossetti’s love succumbs to death. This inversion challenges romantic idealism, presenting affection as fragile and subject to time’s ravages. The poem’s seasonal imagery reinforces this idea: love blooms in spring but withers before autumn, never enduring long enough to be harvested.

2. Mourning as Ritual

The poem constructs mourning as a communal act ("let us make his bed," "sit we by his grave"). This ritualistic framing suggests that grief must be performed, that memory is sustained through shared sorrow. The instruction to "sing" sad and low chords transforms the poem into a kind of dirge, blurring the line between personal lament and universal elegy.

3. Nature and Mortality

Rossetti frequently uses nature to mirror human emotion. Here, the dying flowers and changing seasons parallel love’s demise, reinforcing the idea that all things—even the most fervent passions—are subject to natural cycles. The "shadow-veiled" grass suggests the gradual obscuring of memory, as time distances the living from the dead.

Comparative Analysis

An End can be fruitfully compared to other Victorian meditations on love and death. Tennyson’s In Memoriam, for instance, similarly grapples with grief’s permanence, though his work is more expansive and philosophically searching. Rossetti’s poem, by contrast, achieves its power through compression, distilling sorrow into a few resonant images.

A closer parallel exists with Emily Dickinson’s After great pain, a formal feeling comes, which also examines the ritualized nature of grief. Both poets employ stark, funereal imagery, though Dickinson’s tone is more detached, while Rossetti’s retains a subdued lyricism.

Within Rossetti’s own body of work, An End shares thematic ground with Remember, in which the speaker anticipates her own death and instructs her beloved to forget her. Both poems interrogate the durability of love in the face of mortality, though An End is more resigned in its conclusion.

Biographical and Philosophical Insights

Rossetti’s personal life undoubtedly informs An End. Her two significant romantic relationships—with James Collinson and Charles Cayley—ended disappointingly, the former due to religious differences, the latter because Cayley did not propose marriage until it was too late. The poem’s lament for a love that "would not stay" may reflect her own experiences of unfulfilled affection.

Philosophically, the poem engages with the Victorian crisis of faith. If love, often idealized as eternal, can die, what does that imply about divine love? Rossetti does not offer easy answers, but the poem’s quiet despair suggests a struggle to reconcile human impermanence with spiritual longing.

Emotional Impact

What makes An End so affecting is its restraint. Rossetti does not indulge in melodrama; instead, her grief is measured, almost ceremonial. The directive to "sit we by his grave" invites the reader into the mourning process, creating an intimate bond between speaker and audience. The final lines—"While we think of all that was / In the long ago"—evoke nostalgia without sentimentality, acknowledging that memory is both a consolation and a wound.

The poem’s emotional power lies in its universality. Anyone who has experienced loss—whether of a person, a relationship, or an ideal—can recognize the quiet devastation of love’s end. Rossetti’s genius is in making that devastation achingly beautiful.

Conclusion

An End is a masterclass in elegiac poetry, using sparse language to convey profound sorrow. Through its rich symbolism, personification of love, and seasonal metaphors, Rossetti crafts a meditation on impermanence that is both personal and universal. Situated within the Victorian culture of mourning and her own biographical context, the poem resonates as a poignant exploration of how we grieve what we cannot hold onto.

In the end, Rossetti does not offer solace so much as she offers witness. The act of sitting by love’s grave, of singing sad and low, becomes its own kind of consolation—a recognition that even in loss, there is beauty in remembrance. And in that, An End achieves something timeless: it makes sorrow sing.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!